06 – A SILICA TRUNK PASSING THROUGH RESIN, ARRIVING TO SLAG, AFTER ALL AN ANTHROPOGENIC ARTIFICIAL FULGURITE: THE CURUÇÁ FULGURITE

Ano 11 (2024) – Número 4 – Fulgurites and Sea Glass Artigos

10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v112024i4a6GJV

Marcondes Lima da Costa1*

Glayce Jholy Souza da Silva Valente2

Suyanne Flávia Rodrigues3

José Francisco Berredo4

Alessandro Sabá Leite2

Edna Cabral Trindade5

Dirse Clara Kern3

1Instituto de Geociências (IG) da Universidade Federal do Para (UFPA), Belém, Pará, marcondeslc@gmail.com;

2Instituto de Tecnologia (ITEC), UFPA, Belém, Pará;

3Então do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geologia e Geoquímica, IG-UFPA;

4Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém, Pará;

5Instituto Evandro Chagas, Belém, Pará.

*Author for correspondences

Received on 14.09.2024 and revised and accepted on 23.09.2024.

ABSTRACT

In 2013, a peculiar and large-sized sample was brought to the Geosciences Museum of the Federal University of Pará, thought to look like a tree trunk, resin or even slag. The Curuçá region was confirmed as the area of origin, but the specific location was partially mysterious. . The first studies show that it consists simply of SiO2 in the form of cristobalite and quartz. The origin and occurrence form were soon discovered, which, combined with new mineralogical, chemical and microchemical data, demonstrated that it was an anthropogenic artificial type II fulgurite. The Curuçá fulgurite.

INTRODUCTION

On March 5, 2013, Dr. José Francisco Berredo from Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi sent an email to Prof. Dr. Marcondes Lima da Costa reporting the discovery of silicified plant trunks, found by residents in the region of the municipality of Curuçá, in the northeast of the State of Pará, in a region known as Salgado, in the Atlantic coast domains (Figure 1). It would be linked to the mangrove region, which is very abundant in the region. A sample of this possible trunk was presented to Dr. J. F. Berredo by Mr. Antônio Smith, who would have collected it on February 5, 2013, in the Mocajuba River. Dr. Berredo immediately notices a connection with the large production of amorphous silica, which feeds the formation of large quantities of diatoms, which constitute the sediments of the region’s mangroves, and which in his thesis defended at the Postgraduate Program in Geology and Geochemistry – PPGG from the Federal University of Pará, would explain the transformation, in a short time, of kaolinite carried from the continent to the mangroves, into smectite (Berredo et al., 2017; Vilhena et al., 2017). These trunks would also be a consequence of the abundance of this silica. Intrigued by the discovery, Professor Marcondes expressed a keen interest in further investigating the unusual sample. Then, Dr. Berredo promised to send the sample by Dr. Dirse Clara Kern when she came to the GMGA (Mineralogy and Applied Geochemistry Group) meeting on the subsequent day, March 7, 2013.

The sample was submitted to Prof. Marcondes, who quickly appreciated it, concluded that perhaps it was not silica, but rather vegetable resin, abundant in the region, and that the morphology of the sample could be a mold of a trunk, filled with resin. Or slag from the iron metallurgy industries in Marabá, or metallic silicium in Tucuruí or even aluminum in Barcarena municipalities. And then Dr. Dirse informed that there was much more material, weighing in at many kilos, and how could so much resin be explained? Marcondes countered that it would be possible and gave examples from other locations. He himself had already received blocks of resin measuring almost 40 cm in diameter. The information about the possible place of occurrence was, as normally happens with such apparently strange materials, a mistery, that it would have been found in the region of the municipality of Curuçá, on the Mocajuba River, but this river is large, and the location on the river was not informed. Several rivers in Pará are named Mocajuba. These things inside are always tainted with fanciful stories. And the Salgado region is enriched by these stories, such as ETs, lollipops, etc.

Prof. Marcondes then decided to carrie out laboratory analyzes of the sample, and the obtained results, presented and discussed below, constituted a great surprise: almost total dominance of amorphous silica represented by cristobalite. With the results in hand, which were not in accordance with the initial reports, more coherent information was sought about the sample, and it was discovered that it had in fact come from Curuçá municipality. Drawing upon the initial insights gained from the sample, it was immediately decided to take a trip to Curuçá to find out the real occurrence from the donated sampled material.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Origin of the sample – As mentioned, after discovering the most plausible origin of the sample, the team went to a village in the municipality of Curuçá, northeastern region of Pará, better known as the Salgado region, on April 6, 2013. A vehicle from the Emílio Goeldi Museum of Paraense, with Mr. Lucivaldo as the driver. Marcondes Lima da Costa (IG-UFPA), José Francisco Berredo (MUSEU GOELDI), Alessandro Sabá Leite (PPGG-IG-UFPA), Suyanne Flávia Rodrigues (PPGG-IG-UFPA) and Edna Cabral Trindade (Instituto Evandro Chagas) were on this trip. Our guides were Mr. Francisco and his wife. Francisco Berredo already had the contact information of the person who had been in front of the find. It was Mr. Alfredo de Campos Medeiros, from Curuçá, electrician (technical training at Senai and experience), service provider at Curuçá City Hall. Mr. Alfredo says that the material was found during excavation for electrical repairs carried out in January 2013 at PSF Araquaim (Health Unit) (Figure 1), Curuçá-PA (UC 18012030, located on the Marudá road (coordinates 0.71011 S; 47.76760 W). Fortunately, the PSF equipment was not affected. Mr. Alfredo collected a large amount of material, almost all of what he had found along the way from the former underground wiring, the resin, then silica, to the fine fulgurite. Mrs. Aldiceia, a neighbor of the PSF, reported that a storm with strong electrical discharges occurred in December 2012 (days before Christmas) around 6 am, which burned the transformer and destroyed the PSF’s electrical network. Shortly after this storm accompanied by heavy rain, there was “a lot of smoke coming out of the ground” in front of the PSF. Her dog, afraid of the storm, tried to cross the street and was hit and died. Fortunately, the accident occurred on a weekend, when the PSF was unoccupied, preventing any potential casualties or injuries to staff..

The sample was collected on the ground in front of the Health Unit. It was then that the material was recognized to be fulgurite formed from the electrical discharge on the transformer sitting on the pole in front of the Health Unit, which ran along the copper wiring from the transformer to the sandy-quartz soil and then following it in underground piping to the Health Unit’s power box (PSF Araquaim).

Figure 1 – Location of the PSF Araquaim Health Unit in the municipality of Curuçá in the coastal region of Pará, known as Salgado region. Image from Google Maps.

Figure 2 – Araquaim Health Unit (PSF Araquaim)), in the municipality of Curuá, state of Pará, where the fulgurite was found, on our visit on April 6, 2013. In the images above, a general view of the PSF and detail of the post that distributed energy to the building. In the images below, the electrical wiring path from then on, partially covered, showing the gray sandy soil rich in organic matter. Small fragments of glassy material and patches of green copper compounds could still be observed.

Analytical material – The investigated sample was collected by a third party and is deposited at the Geosciences Museum of the Federal University of Pará, under code 2396, and was analyzed, without knowing its real origin, only because of its very peculiar appearance. It was, therefore, collected on the land in front of PSF Araquaim, along the former underground electrical wiring between the pole and the station’s electricity box. It was then that it was discovered that the material must be a fulgurite formed from the electrical discharge on the transformer and reaching the underground electrical wiring.

Analytical procedures – The analytical procedures consisted first of imaging the sample with a Sony digital camera from various angles, followed by mesoscopic description. Small fragments representing the three zones were subtracted and observed under a stereomicroscope. These fragments were then subjected to chemical analysis using FRX-P (portable x-ray fluorescence), equipment model S1 Turbo from Bruker and SEM/SED (benchtop scanning electron microscopy with benchtop energy dispersive system) from the HITACHI model TM 3000 equipment and the EDS 3000 system with Swift ED software Oxford of LAMIGA of the Geosciences Institute (IG) of UFPA. They were then subjected to analysis by FTIR (infrared spectroscopy with Fourier transform) Vertex 70 Bruker also from LAMIGA and finally analyzed by DRX (x-ray diffraction) from Panalytical in the Mineral Characterization Laboratory of IG.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Morphological aspects – the sample 2396 has an elongated, subcylindrical shape, 26 cm long, with a diameter of less than 10 and greater than 15 cm. Overall, it resembles a fragment of a plant trunk (Figure 2), although it does not present any features related to the plant structure. In cross section, the sample is characterized by a light gray outer zone, with a sandy, saccharoidal, rough, microporous outer surface, about 4 cm thick, massive to porous, encompassing white fragments with gray films and a colloform surface, with 1 to 1 .5 cm thick. There are two subzones, one gray, external, and the other light gray, internal, in sudden contact with the nuclear zone (Figure 3). This internal zone stands out for its cream to yellow, light color, with a tendency towards a central cavity. Its thickness is up to 14 cm and the general appearance is chalcedony or glass, with a greasy shine. It appears massive but is rich in millimeter to centimeter bubble cavities; irregular, interrupted concentric bands are frequent (Figures 3 and 4). It had been thought of as resin, but the absence of insects and plant remains, common in these materials, in addition to the high hardness, ruled out this possibility. Contact between the two zones is generally abrupt. In several samples collected by Mr. Alfredo, similar in size or even smaller than 2396 sample, they exhibited the same appearance, but almost always with the central conduit being very striking, very typical of fulgurites (Figure 5). Due to these aspects and the mode of occurrence, within the top of the spodosol (sandy quartz soils with organic matter (humic), with little kaolinite clay and Fe oxides, it is classified as type II fulgurite by Pasek et al (2012).

Figure 3 – Images of the investigated sample belonging to the collection of the UFPA Geosciences Museum, deposited under number 2396. Clockwise starting with the top image on the left. a) external longitudinal feature, dark gray saccharoidal; b) larger cross section, with multicolored core, core – edge and edge transition, the outer gray zone; c) detail of the multicolored agate-like core; d) transversal section (smaller diameter) with the same areas observed in the larger one.

Figure 4 – Detail of the multicolored internal zone, with cavities derived from bubbles of varying sizes.

Figure 5 – Specimen extracted by Mr. Alfredo, with a typically cylindrical tubular appearance, with an external wall or zone of a very porous gray tone, mainly in the peripheral part, which fades towards the interior, being in abrupt contact with the light cream zone, which supports the conduit (internal channel). There were a few meters of material similar to this. It depicts a typical fulgurite configuration.

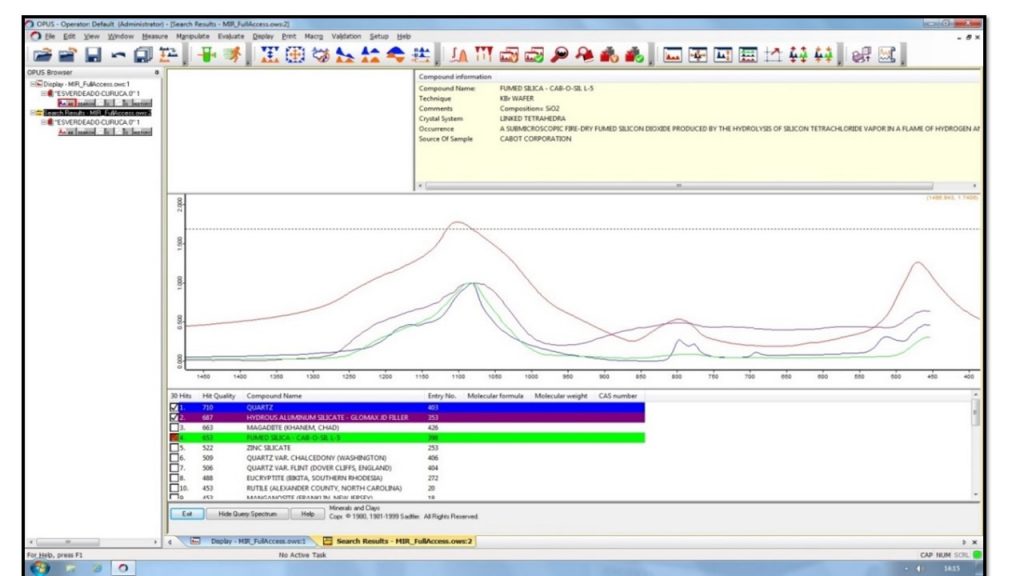

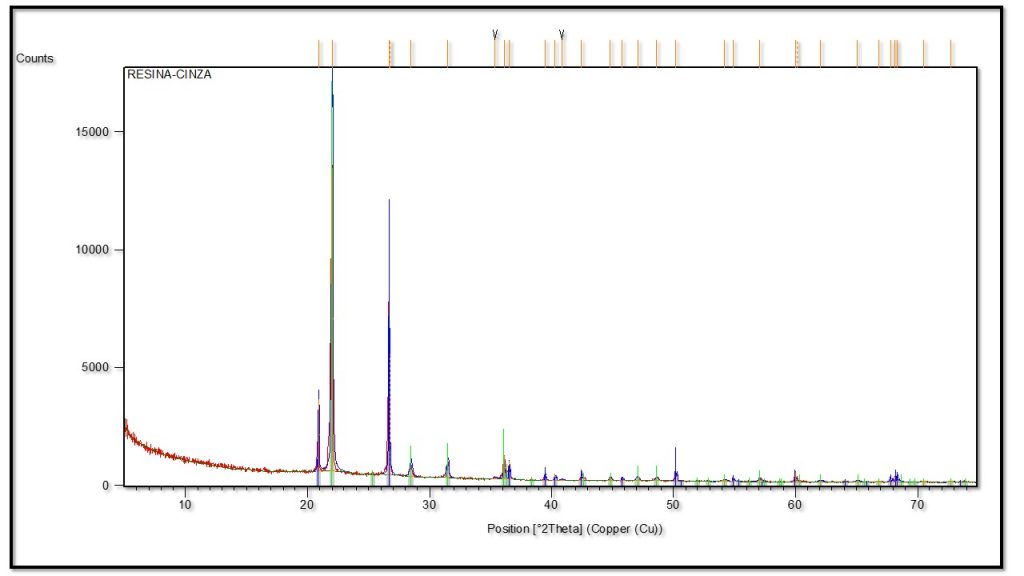

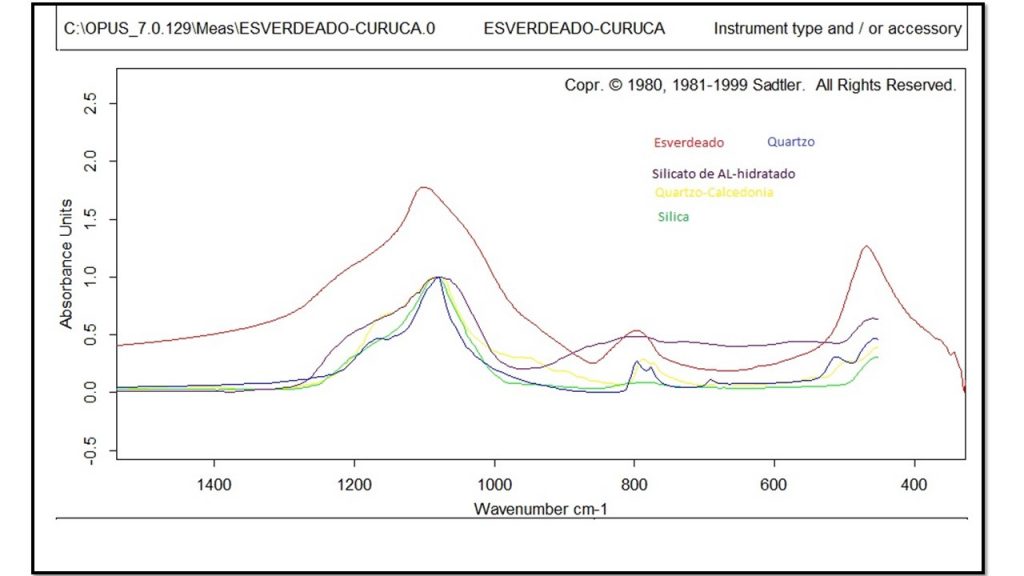

Mineralogical Constitution – XRD analyzes (Figure 6) confirm the dominance of cristobalite, in addition to quartz. FTIR analyzes (Figure 7) recognize opal, which would then correspond, combined with XRD, to opal to cristobalite (opal-C) and quartz, in the zones. Quartz is more abundant in the outer zone, which is normal in most types I and II fulgurites (Pasek et al., 2012). This mineral constitution would not rule out the idea that it could have been a fossilized plant trunk, as admitted at the beginning of the research, but the mode of occurrence has already categorically ruled it out. Most fossil trunks are made of quartz and/or opal. According to Pasek and Pasek (2018), cristobalite has not yet been identified in natural fulgurites, it is found in artificial ones with lechatelierite (SiO2 glass). In the case of sample 2396, the electrical discharge followed the metallic conductor wire (copper) according to the exposure of greenish compounds still present in the soil observed on the field trip, which allows the fulgurite to be classified as artificial. SEM/EDS data will confirm the presence of copper in fulgurite 2396.

Figure 6 – X-ray diffraction spectrum, in which the cristobalite domain is recognized, with restricted quartz in the fulgurite of sample 2396.

Figure 8 – Simplified FTIR spectra from figure 7 for sample 2396 showing compatibility with amorphous silica (opal) and quartz standards.

Chemical Composition – The semi-quantitative chemical analyzes obtained by XRF (Table 1) show that the external (outer wall), internal and transition zones between them are basically made up of SiO2. What was initially thought of as plant trunks could be discarded, although many of them, when fossilized, are dominated by SiO2, both in the form of quartz and opal (Martins et al., 2010), but as already mentioned, the way of occurrence eliminated this possibility. Also noteworthy are the levels of Al2O3 and Fe2O3, both in the same order of magnitude, but below 4%. The red spots in the core and the dark gray colloform material at the edges are richer in Fe2O3. CaO and K2O contents are <0.11%, except in one analysis (Table 1). Sodium is not detected by the method, but as shown in the next topic, it was not identified by SEM/EDS, while Mg was not identified, being below the detection limit of the instrument, and was also rarely identified by SEM/EDS. Even if discarded, the analysis was compared with that of a fossil trunk specimen (dominated by chalcedonic quartz), which is much richer in SiO2. Considering the mode of occurrence in quartz-rich soils, the mineralogical characteristics that point beyond cristobalite and the presence of quartz, and the high levels of SiO2 (up to 82%), which are higher in the internal zone, it can be deduced that the Curuçá fulgurites were actually formed from the fusion of quartz-rich soils, of the spodosol type, which is dominant in the region. For comparison purposes, as the total chemical composition of this type of soil was not found in the region, the chemical composition of spodosol from the northern region of Manaus—Presidente Figueiredo in the state of Amazonas, horizon B (Table 1), formed of quartz (84 %), kaolinite (15 %) and hematite/goethite (1%)) (Horbe et al. 2004) was used for comparison. The chemical similarity between the Curuá fulgurite and the Manaus-Presidente-Figueiredo spodosol is strong, both in terms of SiO2 and other elements, with emphasis on the very low levels of alkali metals. For Pasek and Pasek 2018, SiO2 content below 90% indicates target material such as sandy (quartz) soils with clay, corresponding to type II fulgurites. This is because the additional elements increase the liquidus region for melts of these materials, and hence an expanded glassy zone is formed over a larger thickness, surrounds the glass of type II fulgurites, resulting in much larger diameters. This is exactly what has been observed by Curuçá fulgurites.

Table 1 – Chemical composition of the sample 2396 in its three zones, obtained by handheld FRX. dl: below detection limit; nd: not determined.

| Gray zone | Transition | Core zone | Gray zone | Transition | Core zone | Fossil wood1 | Spodosol

Bhorizon2 |

|

| Al2O3 | 3,19 | 2,15 | 2.17 | 2,02 | 2,3 | 2,87 | 0.15 | 5.84 |

| SiO2 | 60,3 | 68,7 | 81,2 | 79,8 | 74,6 | 82 | 97.27 | 90.78 |

| K2O | 0,04 | 0,02 | 0,03 | 0,05 | 0,05 | 0,11 | 0.06 | 0,01 |

| Na2O | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0,01 |

| CaO | 0,31 | 0,06 | 0,1 | 0,1 | 0,09 | 0,09 | 0.03 | 0,01 |

| MgO | dl | dl | dl | dl | dl | dl | dl | 0,14 |

| MnO | dl | dl | dl | dl | dl | dl | dl | 0,08 |

| TiO2 | 0,55 | 0,28 | 0,36 | 0,38 | 0,33 | 0,36 | 0.01 | 0,20 |

| Fe203 | 1,62 | 1,88 | 1,13 | 4,41 | 2,7 | 1,09 | 0.05 | 0.42 |

Obs.: Sodium cannot be determined by handheld XRF; however, it was detected by SEM/EDS. 1 Fossil wood from Pedra de Fogo Formation (Martins et al. 2010); chemical composition by microprobe analyzes; 2. Horbe et al. (2004).

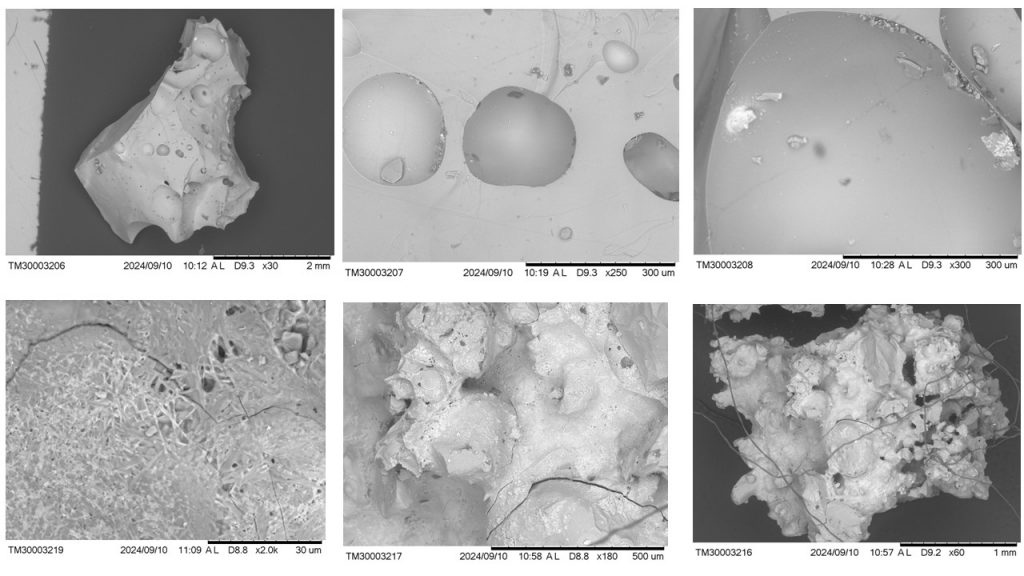

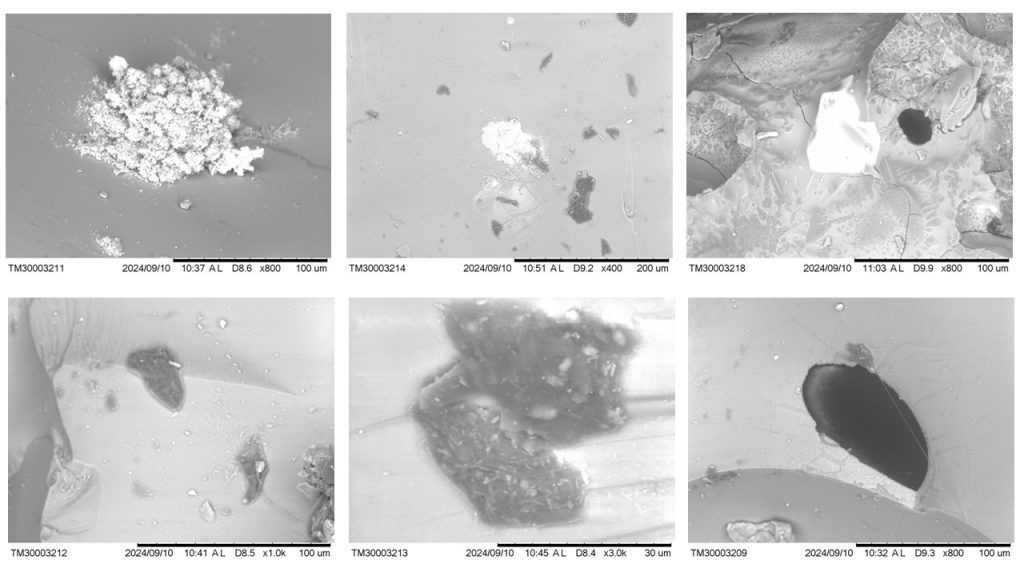

Figure 9 – Micromorphological aspects of sample 2396 obtained with SEM. Above from left to right (a, b, c; respectively): typical fragment of glass with classic bubble voids; images of bubble cavities in the glass; the glass with inclusions of mineral neoformation (white hue: to the left, Cu and Fe; to the right, Fe and Cu) and with dark gray spots (with a marked presence of S and Cl). Below from left to right (d, e, f; respectively): lattice or reticular micro texture, and dark gray dots, perhaps lechatelierite; glass with botryoidal aspects, looking like an explosive material; glass with a slag appearance on a gray background. Figure 9d is presented in enlarged form in Figure 11, with microchemical analysis.

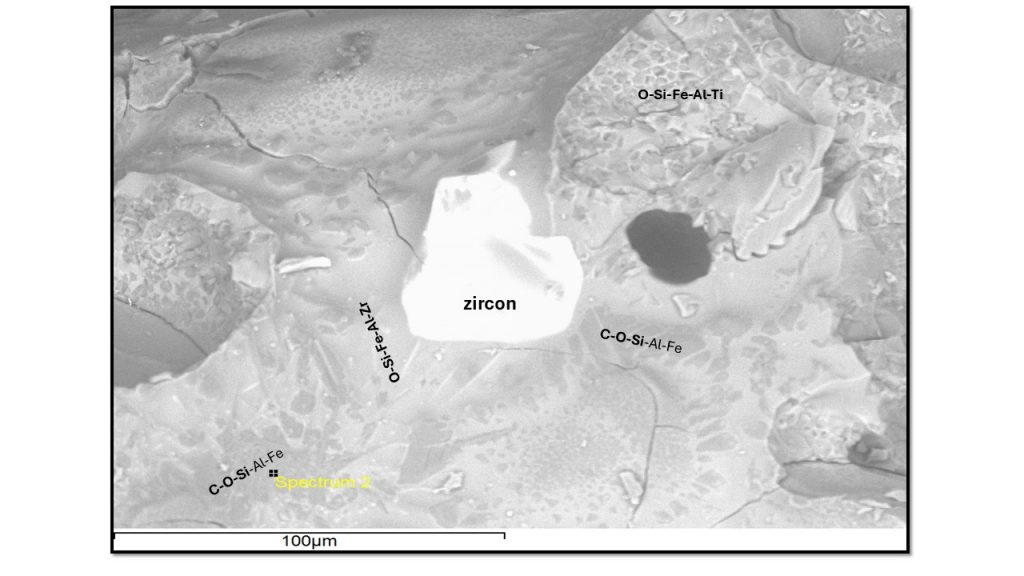

Figure 10 – Micromorphological aspects of sample 2396 obtained with SEM. Top images from left to right (a,b,c; respectively): appearance of micro slag (whitish) in almost solid glass (gray); glass with inclusions in white tones (with Cu and Fe) and dark gray (lechatelierite?); relict of zircon in a glass environment, still showing a morphology suggestive of quartz grains, black inclusion (O-Si-C mainly, Al-Fe restricted). Below from left to right (c,d,e; respectively): glass with dark gray inclusions of lechatelierite; another dark gray inclusion with light gray crystallites in a glassy mass, also of lechatelierite; glassy mass with black inclusion (O-Si-C-Al-Fe domain).

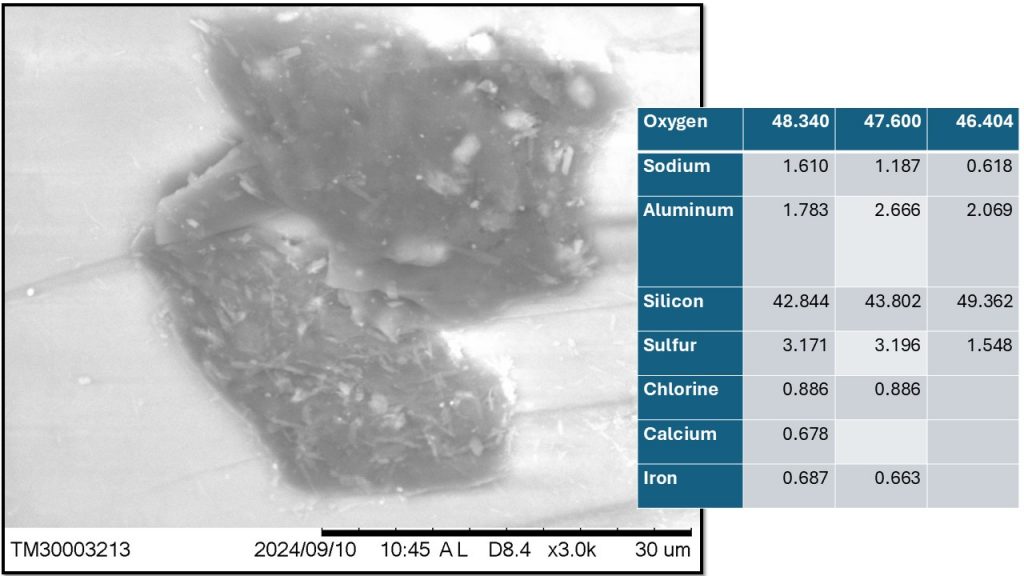

Micromorphology and spot chemistry – The micromorphological images obtained with SEM show the dominant glassy nature, therefore cristobalite, with numerous voids in the shape of micrometric bubbles, lattice or reticular textures, ovoid features, flow, micro-slags, and inclusions of “minerals” or neophases, and rare remaining mineral phases (Figures 9 and 10). The domain is in fact made of glass (Figure 9), a typical appearance of a completely molten and quickly solidified material. In the vitreous mass, divergent shades of gray can also be recognized, suggesting discrete “mineral” phases, lechatelierite, probably. Spot microchemical analyzes obtained with SEM/EDS show a dominance of O, Si and C, with discrete concentrations (< 3.0%) or not of Al, Fe, Ti (Table 2), where Ti is always below 0, 4%, except in some microphases. The significant carbon concentration is noteworthy, which locally can reach 47.7% (slag inclusion, C-O-Si, with traces of Cu; probable PAH: polyaromatic hydrocarbons, which are also found fulgurites ((Elmi et al., 2017; Carter et al., 2010), or fullerenes (Daly et al., 1993; Heymann, 1996). These results show that the original raw material (target material) for the formation of glass was basically quartz, therefore silica, and more strictly. aluminosilicate type kaolinite? and perhaps Fe oxyhydroxide, such as spodosols, which mainly contain organic matter in the form of humus. However, as previously highlighted, the glass domain locally presents significant chemical variations. In the micro areas dominated by bubble forms, the chemical composition of the glass is similar to the general one, tending to a higher concentration of carbon and less oxygen, with Al and Fe varying within the general range (Table 2), and always below 2.6 %. In the glass mass, a white inclusion in the SEM image corresponds to neomineral or neophase of Cu, Fe and S (Figure 9 c; Table 3, analysis 1: perhaps Fe-Cu sulfide, bornite?). It is worth highlighting the Cl levels. While the other on the right (Fig.9c; Table 3, analysis 2) is Fe-Ti, in K, Ca aluminosilicate glass. It is noted that although in general, the fulgurite is poor in alkali metals, in micrometrical scale, they are concentrating in microphases. The white inclusion in Fig.10b is also Fe-Ti, but with restricted Ti content. It is interpreted as Ti-magnetite. Copper, certainly, comes from electric wires and the other elements like Fe, Ti, Al ans some K, Ca, from the soil. S and Cl may be related to organic material (humus) of the soil (target material), too. At the site it appears that the spinning was at the top of the spodosol domain profile with a humic A horizon. It is possible to identify secondary formations of Cu minerals, through their greenish manifestations, probably post-discharge pedogenetic neoformation. The dark gray inclusions in the vitreous matrix (Fig.10 b,d.e; Table 3 analyzes 4 to 7) are amorphous, lechatelierite type, with contents of Na, S, Cl, in addition to Al, Fe, Ca; but does not contain C, which is present in the adjacent glassy mass. The glassy mass with a coliform appearance, suggesting explosive bubbles, presents great chemical variation (Table 4, analyses, 1 to 3), suggesting heterogeneous material during gaseous formation.

A zircon grain was detected (Fig. 10c, Tab.4, analysis 4) in a heterogeneous physical and chemical glassy mass, but with delineation of possible quartz grains. However, the zircon appears to have been partially melted, as shown by the texture and chemical composition surrounding the grain relic (Fig. 10c and Tab. 4, analysis 5). It suggests an incongruent melting for this mineral (Pasek et al 2012) and demonstrates that the melting temperature of the parent material contained zircon grains, and that the temperature reached the melting temperature of zircon (2,550 o C) and proves that the cooling was indeed rapid. Similar behavior has been identified in fulgurite by Block (2011); a detrital zircon grain shows baddeleyite rim in its outer zone.

Pasek et al 2012 also recognize zircons strongly modified by the fulgurite formation process. While in type I fulgurites it is always as Zr oxide in the melting, in type II it is still present but displays a halo showing incongruent melting for this mineral. The temperature at which zircon begins to break down is about 1,950 K, placing constraints on the minimum temperature reached during fulgurite formation.

Table 2 – SEM/EDS microchemical composition of the glass domain and bubble micro areas in glass. nd: not detected.

| Glass | Bubble-bearing micro areas in glass | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Carbon | 15.660 | 6.231 | 8.372 | 9.842 | 12.650 | 18.248 | 7.738 |

| Oxygen | 44.948 | 57.599 | 58.219 | 55.651 | 56.441 | 52.353 | 57.305 |

| Aluminum | 2.342 | 0.364 | 0.540 | 2.399 | 2.412 | 1.813 | 0.841 |

| Silicon | 35.877 | 35.807 | 32.869 | 31.146 | 27.336 | 26.105 | 33.421 |

| Titanium | nd | nd | nd | 0.165 | nd | nd | 0.432 |

| Iron | 1.174 | nd | nd | 0.797 | 1.161 | 1.481 | 0.264 |

Table 3 – SEM/EDS spot chemical composition of mineral (neo phase) inclusions.

| Whitish inclusions: Fe-Cu; Fe-Ti | Dark gray inclusions (lechatelierite) | |||||||

| 1.Fig.9c | 2.Fig.9c | 3.Fig.10b | 4.Fig.10d | 5.Fig.10d | 6.Fig.10e | 7.Fig.10e | 7.Fig.10b | |

| Oxygen | 34.194 | 46.116 | 51.763 | 64.914 | 57.534 | 48.340 | 47.600 | 64.638 |

| Sodium | 1.206 | 1.722 | 0.314 | 1.610 | 1.187 | 0.710 | ||

| Magnesium | 0.440 | 1.052 | ||||||

| Aluminum | 1.088 | 11.523 | 1.248 | 1.123 | 2.589 | 1.783 | 2.666 | 3.153 |

| Silicon | 7.220 | 13.740 | 11.250 | 27.118 | 35.703 | 42.844 | 43.802 | 24.146 |

| Sulfur | 6.254 | 1.250 | 3.176 | 1.636 | 3.171 | 3.196 | 2.894 | |

| Chlorine | 3.656 | 1.036 | 0.844 | 0.319 | 0.886 | 0.886 | 0.657 | |

| Potassium | 0.893 | 0.333 | 0.204 | 0.891 | ||||

| Calcium | 1.110 | 0.368 | 0.266 | 0.663 | 0.692 | 0.678 | 0.426 | |

| Titanium | 4.293 | 0.447 | ||||||

| Iron | 18.506 | 23.628 | 27.937 | 1.212 | 0.687 | 0.663 | 0.986 | |

| Copper | 27.079 | 3.841 | ||||||

Table 4 – Colloform glass (explosive bubbles) or like slag; zircon relict grain, Zr-glass and lattice pattern illustrated in the Fig.12.

| Description |

Colloform glass |

Zircon domain grain | Zirconium iron glass rim | Carbon rich gray zone near zircon | Lattice or reticular glass | ||

| 1.Fig.9e | 2.Fig.9e | 3.Fig.9e | 4.Fig.10b | 5.Fig.10c | 6.Fig.10c | 7.Fig.9d | |

| Carbon | 26.832 | 6.256 | 38.074 | ||||

| Oxygen | 48.862 | 53.529 | 62.829 | 50.742 | 44.648 | 41.536 | 50.617 |

| Magnesium | 0.553 | 0.839 | |||||

| Aluminum | 5.306 | 10.194 | 0.536 | 2.265 | 5.980 | 3.432 | 13.207 |

| Silicon | 16.462 | 24.697 | 30.380 | 15.131 | 24.738 | 13.276 | 27.179 |

| Potassium | 0.482 | 0.638 | 0.448 | ||||

| Calcium | 0.677 | 0.671 | 3.984 | 0.685 | 0.653 | ||

| Titanium | 1.311 | 1.106 | 0.563 | 1.148 | |||

| Iron | 2.538 | 8.557 | 1.705 | 14.756 | 2.434 | 5.910 | |

| Zirconium | 29.486 | 4.149 | |||||

Figure 11 – Dark gray inclusion with white crystallites, whose chemical composition relative to the proportion of O and Si would correspond to lechatelierite surrounded by cristobalite. The crystallites can be sulfur and/or Fe oxides or neoformed aluminosilicates.

Figure 12 – A relict zircon core (white) partially fused generating a halo of glass with Zr and Fe (light gray rim) and surrounded by C-O-Si glass with Al-Fe (gray background). At the top of the image the lattice or lattice or reticular pattern of Fig. 9d, formed by aluminosilicate (gray tone) and Fe-Ti (perhaps Ti-magnetite) (light gray to white tone).

This lattice or reticulated pattern was verified by Block (2011), corresponding to metal blebs, these large metal blebs show metals of varying Fe and Si composition. The author identified Fe3Si, gupeiite (light gray) and Fe5Si3, xifengite (medium gray) and FeSi, fersilicite (dark), which apparently would not correspond, but could be, to Curuçá fulgurite. They were not clearly detected in fulgurite 2396, but certainly new analyzes with emphasis on high-resolution SEM/EDS and backscattering images are necessary. Although they have not been identified, the presence of carbon in high concentrations in cristobalite glass suggests that it is present as PAH or as Si and Fe carbides, as they are common in fulgurites (Pasek et al., 2012; Elmi et al. 2017; Pasek & Pasek, 2021; Research in this direction should be encouraged.

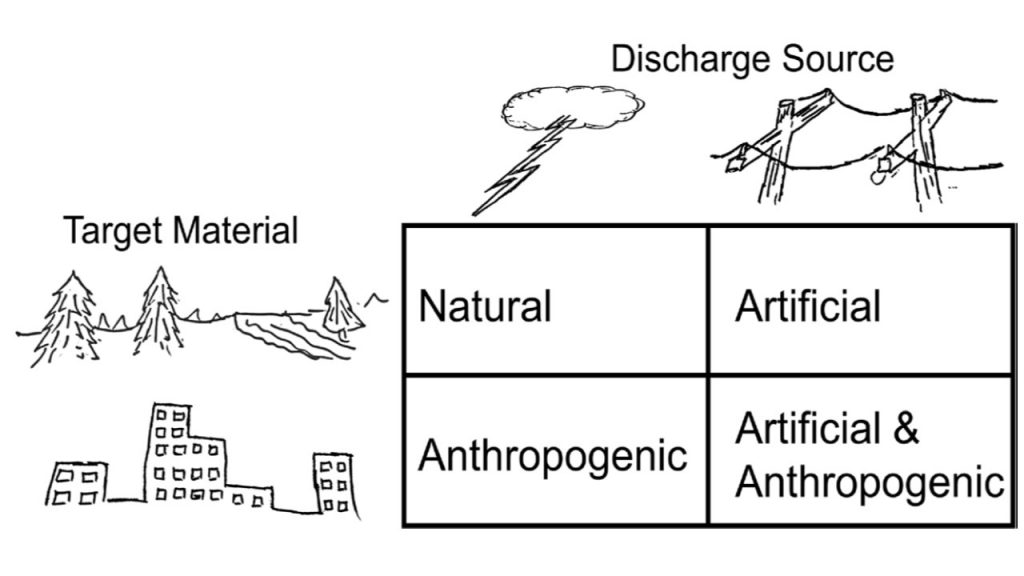

Certainly, MUGEO sample 2396 represents a typical fulgurite, developed in the top horizons of sandy quartz soil, equivalent to spodosol. In the classification by Pasek et al. (2012) would be type II. On the other hand, due to its origin, it would be artificial, following the argument of Pasek & Pasek (2018) (Figure 13), as the lightning hit a post with a transformer and copper electrical wiring, through which the energy reached the ground sand quartz with a humic horizon, within which, due to the high discharge, the temperature rose and the quartz melted, favored by organic matter. In addition to being artificial, it would be anthropogenic, as the fusion and the respective glass incorporated not only material from the soil but also from the electrical wiring, which is of anthropogenic origin. Therefore, the target materials were natural soil and electrical wiring with its plastic covering (insulator). The high thickness shows that the target materials were favorable to the fusion following the sub-horizontal position of the wiring. The role of copper electrical wiring is undeniable. Organic matter and the presence of clay minerals (kaolinite) in the soil certainly contributed to promote this. The elevated temperature is indicated by the formation of cristobalite and incongruent melting of zircon.

Figure 13 – Schematic providing new fulgurite terms proposed by Pasek & Pasek (2018) for those which includes some anthropogenic target material.

CONCLUSIONS

The beautiful MUGEO sample 2396 with a trunk appearance, mistaken as resin, initially involved in many controversies, and “popular folklore stories”, which even looked like slag, due to the way it is a molten and quickly solidified material, glass, is in fact something rare, a beautiful grandiose fulgurite, artificial and partly anthropogenic. On March 11, 2013, during a technical visit made by Bruker’s sales specialist, Mr. Luciano Santos, with long experience in Metallurgy, upon seeing the sample, he said: “where does this slag glass come from?”

It is a cristobalite fulgurite, with relict quartz, and neoformation of lechatelierite, whose chemical composition is dominated by SiO2, but still carbon, which could be in the form of PAH or Si and Fe carbides, frequent phases in fulgurites.

Its formation could have caused a serious accident for PSF Araguaim personnel, if the storm had occurred on weekdays. Fortunately, it was the weekend. While most classic fulgurites are a few centimeters thick, tending to be vertical, fulgurite 2396 is very thick, typically sub-horizontal, and appears to have reached a few meters in length, as deduced from the number of samples. collected by Mr. Alfredo.

The final verdict in turn serves as a lesson to the curious, hurried observers, in which the majority present themselves with one or more stones, thinking that they are in front of a treasure, and because of this they hide valuable information, which would allow them to eliminate this analytical path, if true information about the origin of the material had been presented. This was hit in the Curuçá mangrove, a region devoid of metallurgy, in addition to the sample does not contain mangrove soil material.

Acknowledgments

To CNPQ for granting a Bench Fee and Productivity Scholarship to ML Costa (Process number 304967/2022-0); to Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi for providing a vehicle for field work and to the Mineral Technology Laboratory of the Institute of Geosciences at Federal University of Pará for the XRD run.

REFERENCES

Berredo, J.F.; Costa, M.L.; Vilhena, M.P.S.P.; Rafaela, C.L.2017.A Influência Das Áreas-Fonte Para Os Sedimentos Dos Manguezais Da Costa Paraense: Consequências Mineralógicas E Geoquímicas. Boletim do Museu de Geociências da Amazônia (BOMGEAM), v. 4 (2017), p. 1-5, 2017. 10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v42017i2a1JFB

Block, K.M. 2011. Fulgurite classification, petrology, and implications for planetary processes. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the department of planetary sciences the University of Arizona. 69p. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/144596

Carter, E. A.; Hargreaves, M. D.; Kee, T. P.; Pasek, M. A.; Edwards, H. G. M. 2010. A Raman spectroscopic study of a fulgurite. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 368(1922), 3087–3097. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0022.

Dubroeucq, D.; Volkoff, B. 1998. From Oxisols to Spodosols and Histosols: evolution of the soil mantles in the Rio Negro basin (Amazonia). , 32(3-4), 0–280. doi:10.1016/s0341-8162(98)00045-9.

Daly, T. K.; Buseck, P. R.; Williams, P.; Lewis, C. F. 1993. Fullerenes from a Fulgurite. Science, 259(5101), 1599–1601. doi:10.1126/science.259.5101.1599.

Elmi, C., Chen, J., Goldsby, D., & Gieré, R. 2017. Mineralogical and compositional features of rock fulgurites: A record of lightning effects on granite. American Mineralogist, Volume 102, pages 1470–1481, 2017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2138/am-2017-5971.

Hess, B.L., Piazolo, S. & Harvey, J. 2021. Lightning strikes as a major facilitator of prebiotic phosphorus reduction on early Earth. Nat Commun 12, 1535 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21849-2.

Heymann, D. 1996. “Chemistry of Fullerenes on the Earth and in the Solar System: A 1995 Review” (PDF). LPS. XXVII: 539. Bibcode:1996LPI….27..539H.

Horbe, A.M.C.; Horbe, M.A.; Suguio, K. 2004. Tropical Spodosols in northeastern Amazonas State, Brazil. Geoderma: 119(1-2): 55–68. doi:10.1016/s0016-7061(03)00233-7

Martins, R.A., Costa, M.L. & Moraes, M.S. 2010. Floresta fossilizada do Tocantins: uma flora preservada por milhões de anos. Natal – RN: Editora IFRN, 120p.

Pasek, M.A., Block, K. & Pasek, V. 2012. Fulgurite morphology: a classification scheme and clues to formation. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 164, 477–92. DOI 10.1007/s00410-012-0753-5.

Pasek, M.A. & Pasek, V.D. 2018. The forensics of fulgurite formation. Mineralogy and Petrology 112, 185–98. DOI: 10.1007/s00710-017-0527-x.

Vilhena, M. P. S. P. ; Costa, M. L.; Berredo, J. F; Paiva, R. S. ; Moreira, M.Z. 2017.The sources and accumulation of sedimentary organic matter in two estuaries in the Brazilian Northern coast. Regional Studies in Marine Science, p. 2-10.