03 – MINERALOGY AND GEOCHEMISTRY OF SEDIMENTS AND SOILS FROM BANANAL ISLAND: INSIGHTS INTO LATE QUATERNARY LANDSCAPE EVOLUTION

Ano 12 (2025) – Número 4 Artigos

https://doi.org/10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v122025i4a3LASM

MINERALOGY AND GEOCHEMISTRY OF SEDIMENTS AND SOILS FROM BANANAL ISLAND: INSIGHTS INTO LATE QUATERNARY LANDSCAPE EVOLUTION

Laís Aguiar da Silveira Mendes1, Marcondes Lima da Costa2, Maria Ecilene Nunes da Silva 3*, Hermann Behling4

1Doutoranda conclusa (2019) do PPGG/IG-UFPA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

2Federal University of Pará, Institute of Geosciences, Rua Augusto Corrêa, 1, 66075-110, Belém/Pará, Brazil

3Federal University of Tocantins, Palmas, Tocantins, Brazil

4University of Göttingen, Department of Palynology and Climate Dynamics, Albrecht-von-Haller-Institute for Plant Sciences, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany

ORCID IDs:

Laís Aguiar da Silveira Mendes – https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1271-1769

Marcondes Lima da Costa – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0134-0432

Maria Ecilene Nunes da Silva – https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3071-3098

Hermann Behling – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5843-8342

*Corresponding author: Maria Ecilene Nunes da Silva. Federal University of Tocantins, Palmas, Tocantins, Brazil. Cel. +55 63 984638481. Email: mariaecilene@yahoo.com.br

ABSTRACT

The Bananal Island is a seasonal wetland, included in the extensive Araguaia floodplain. To investigate the landscape dynamic of Bananal Island during the Late Holocene, four sediment and soil profiles were collected from both Araguaia and Javaés rivers margins and analyzed for sedimentological aspects, soil textures, mineralogy and whole chemistry. The results demonstrate a dynamic landscape characterized by recurring cycles of erosion, sedimentation, and ferruginization, primarily driven by seasonal river dynamics. The study highlights the formation of distinctive sedimentary features, including iron-stained sands and floodplain deposits, as well as the influence of these processes on the region’s biodiversity. The findings highlight the ongoing transformation of Bananal Island’s landscape and the significant role of both ancient and modern riverine influences in shaping its unique geological and ecological characteristics.

Key-words: Bananal Island, landscape evolution, sediments and soils, weathering processes.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Bananal Island is a significant geographical feature located in the Tocantins State, Brazil, renowned for its vast size and unique ecological characteristics. Formed by the confluence of the Araguaia River and its tributary, the Javaés River, it is often considered the largest fluvial island in the world, spanning approximately 20,000 square kilometers (Borma et al..2009). The island is an integral part of the extensive Araguaia floodplain, which covers a substantial area of approximately 58,600 square kilometers in the southeastern region of the Amazon Basin. This floodplain ranks as the fifth largest of its kind in South America (Melack and Hess 2010).

Due to its location within a floodplain, Bananal Island experiences seasonal flooding during the rainy season. The combination of local precipitation and a saturated water table results in temporary inundation, classifying it as a seasonal wetland (Valente 2007). This unique hydrological regime significantly influences the island’s ecosystem and biodiversity.

Wetlands are areas of global interest, because they are sensible to environmental changes. Mitchell et al. (2010) elucidated the importance of the wetlands stating they are important to the process of groundwater recharge, flood control, maintenance of biodiversity, and may support some agriculture activity and fishing. Such sensible environments must be used for conservation because they support rich biodiversity, by providing habitat for large variety of animal and plant species, since they display chemicals, physical and biological characteristics, which are very important for the life cycle, including rare and specific species of plants and animal, exploring the distinct, ecosystems, landscapes and processes.

Recent studies have been carried out on the Bananal basin wetlands concerning fluvial dynamics of the Araguaia River (Coe et al. 2011, Latrubesse et al. 1999), the geomorphological evolution (Latrubesse and Stevaux 2002, Aquino et al.2009, Latrubesse et al. 2009, Valente and Latrubesse 2012, Valente et al. 2013), hydrological processes (Aquino et al. 2005, Morais et al. 2008) and vegetation dynamics (Mendes et al. 2015). However, the mineralogical and geochemical contribution to understanding the evolution of this landscape is still scarce. In this context, the aim of this work is to provide such data and discussion using the young sediment and soils records in the Northern Region of Bananal Island and surrounding areas in order to understand the landscape dynamic during the Late Quaternary in this classical wetland.

1.1 Study area

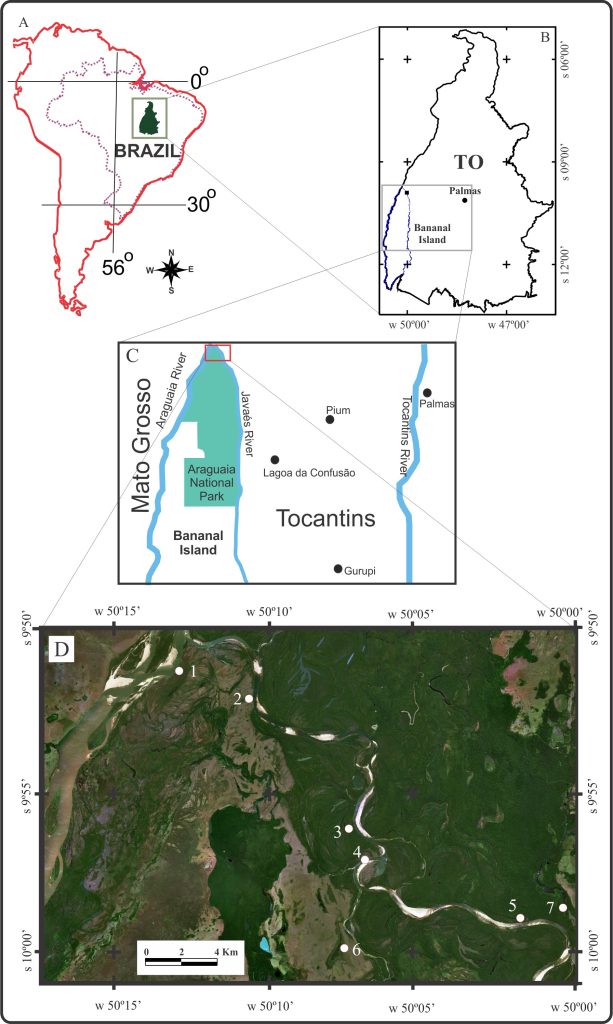

The study area is located in the northern portion of the Bananal Island, between coordinates 9º51’28.2″ S and 9º58’48.2″ S, 50º2’13.4″ W and 50º12’43.9″ W (Fig. 1). The Bananal Island comprises a transitional area between Amazon rainforest and Brazilian Cerrado biomes. The regional climate is warm and semi-humid. The average annual precipitation varies from 1,400 to 2,200 mm/year. The rainy season occurs from November to April. The dry season is marked by very low or no precipitation, and the driest months range from June to September. The average annual temperature is 26°C, the maximum temperature of 38°C occurring during the months of August and September (Dias et al.2008).

According to Brasil (1981) the Bananal Island seasonal wetland consists of a morphological unit characterized by a fluvial-lacustrine plain, with numerous lakes, lagoons and intermittent channels. The hydrogeomorphologic features of this wetland include hills, valleys, abandoned channels, oxbows lakes, related to high relief-energy relationship (Latrubesse et al. 2009). The Bananal Island is drained by Araguaia and Javaés rivers and their tributary streams in the center of the Island, mainly the Jaburu and Riozinho rivers. River channels within the floodplain tend to present anabranching pattern (Valente et al. 2013).

This landscape is geologically inserted in the Bananal Basin whose Quaternary sediments belongs to Araguaia Formation, 170-320 m thick, composed by yellowish to brownish unconsolidated sediments, silt to sand grain size and locally ferruginized (Araújo and Carneiro 1977).

The vegetation is composed of a mosaic of rainforest and savanna (cerrado). In this context, savanna presents variable physiognomies since grassland savanna (dominant herbaceous stratum with rare bushes and absence of trees) to shrub savanna and wooded savanna. The shrub savanna is a mixed herbaceous-shrub vegetation, with bushes and trees scattering in an extensive grassy cover, where Byrsonima sp., Curatella americana and Tabebuia sp. are the shrubs and tree types dispersed along the herbaceous stratum. In the wooded savanna, the same trees occur but form denser groups.

The forest formations appear like gallery forest that consists of the perennial forest occurs alongside of Araguaia and Javaés rivers and their tributaries, for example, Riozinho stream that cross the Bananal Island. Forest fragments are common along the abandoned channels and floodplains associated with shrub savanna species.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

To investigate the regoliths (soils and sediments) and to understand their relationships landscape’s components (relief, vegetation cover, water bodies, etc.), four profiles (Coco Beach, White Barrier, Collapsed Ravine, Canguçu Harbor) along the exposed banks of the Javaés and Araguaia rivers. (Fig. 1) were described and sampled. These selected profiles are representative of the geomorphic, pedological and botanical patterns found in the study region. These regolith samples were submitted to analyses such as grain size, mineralogy by XRD (X- Ray Diffraction) and whole chemistry by ICP-AES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy) for the major elements and ICP-MS (Inducted Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer) for the trace elements. Additionally, three samples (C1, C2, and C3) of reddish and greenish colloidal material were collected in a Javaés River sandbar so-called Long Beach. This material was submitted to mineralogical and chemical analyses by XRD, FTIR (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy), SEM/EDS (Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy) and thermal analyses by TG (thermogravimetry), DTG (derivative thermogravimetry) and DSC (differential scanning calorimetry) techniques. All analytical procedures were conducted in the laboratories of the Institute of Geoscience at the Federal University of Pará (IG/UFPA), except for ICP-AES/ICP-MS analysis, which was performed at commercial ALS Laboratories.

Figure 1. Localization maps of the study area: A) location of Tocantins State in South America; B) Bananal Island location; C) detail of Araguaia National Park localized in the north of Bananal Island, and in the red square the study area; D) coring sites location: 1. Collapse Ravine – PDZ; 2. White Barrier – BB; 3. Coco Beach – COCO; 4. Long Beach; 5. Canguçu Harbor – CANG.

The grain size analysis consists of the separation of the sand, silt and clay fractions through wet screening according to procedures adopted by Embrapa (1997). The samples with the lowest sand content were performed by laser diffraction with the Fritsch Granulometer model Analysette 22, 2 g of samples with dispersion in water. The sand grain fraction was observed as about the roundness and sphericity by visual comparison with the tables of rounding and sphericity classes presented by Suguio (2003).

The XRD mineral analyses were carried out by using a powder diffraction method with a Bruker diffractometer model D2 Phaser, with copper anode (λKα1 = 1.5406Å), operating with 40 mA currents, 40 kV voltage, with a step size of 0.02º (2θ), a count time of 5 s, at an angular range of 5-70º (2θ). To perform the clay minerals (fine fraction < 2mm), the samples were previously prepared using slide orientation technique, in addition, they were air-dried, solvated with ethylene glycol for 24h and heat-treated at 500ºC during 2h. The diffractograms of fine fraction (< 2mm) were recorded with the PANalytical diffractometer model Empyrean, with cobalt anode (λKα1 = 1.78901Å), PIXCEL3D-Medpix3 1×1 detector operating with 35mA current, 40 kV voltage, with a step size of 0.02º (2θ), at an angular range of 5-70º (2θ), time of 10 s. The results were treated with the X’Pert High Score Plus software, which compares the obtained peaks with those from the International Center on Diffraction Data (ICDD) and presented with symbols according to Siivola and Schmid (2007).

The FTIR measurements were performed with an infrared spectrometer model Vertex 70, Bruker, using OPUS 7.0 software, with operating conditions in the 4000 to 400 cm-1 regions at a resolution of 4 cm-1. Samples were prepared following standard procedures (0.0015 g of sample + 0.2 g of KBr) to produce a pressed pellet. This analysis is necessary for cases where the sediments do not have formed minerals, i.e., they are amorphous or in neoformation; the SEM/EDS analyses were performed using the HITACHI model TM 3000 equipment and the EDS 3000 system with Swift ED software coupled with the SEM.

The TG, DTG and DSC measurements were performed in a NETZSCH thermal analyzer model STA 449F3 Jupiter with a simultaneous thermal analyzer from Stanton Redcroft and a platinum vertical cylindrical oven. A temperature between 25 ◦C and 1000 ◦C was used in a nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 50 cm3/min. The heating rate was 5 ◦C/min, with a platinum crucible as a reference.

3 RESULTS

- Lithological succession of the sediments

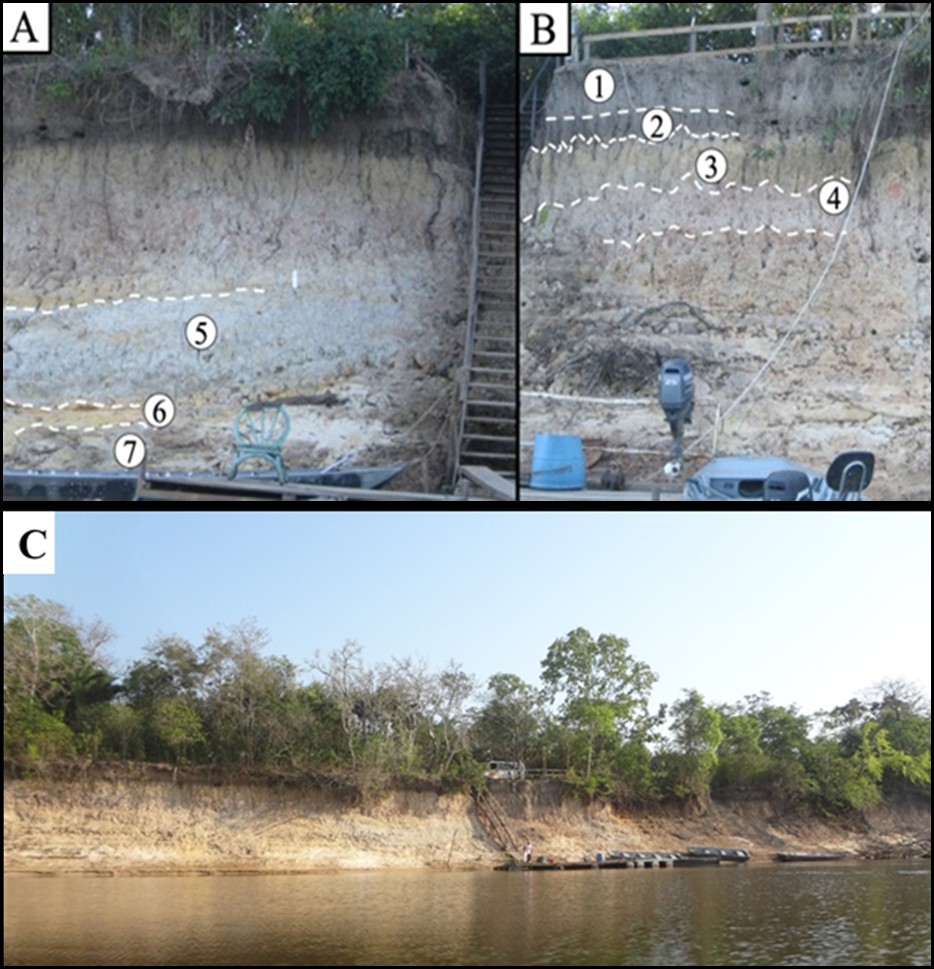

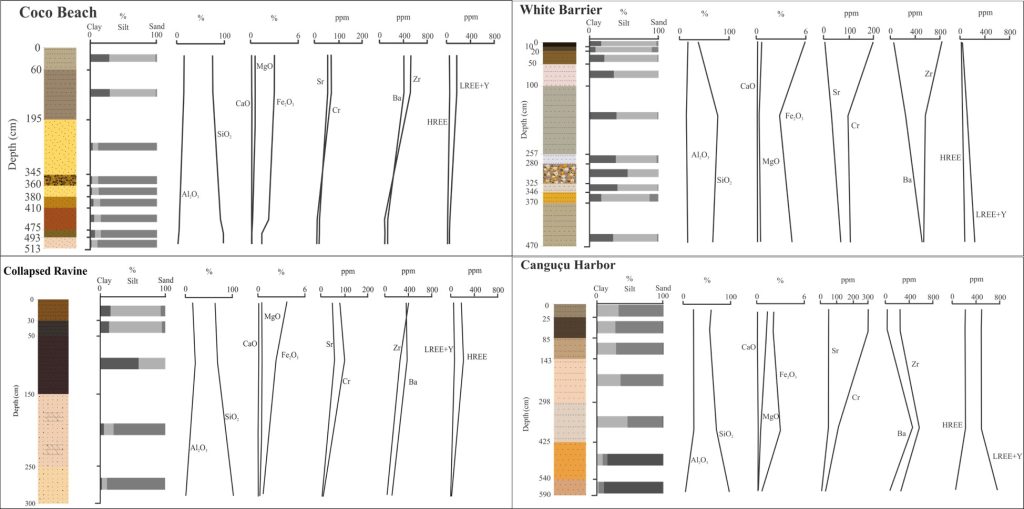

3.1.1 Coco Beach

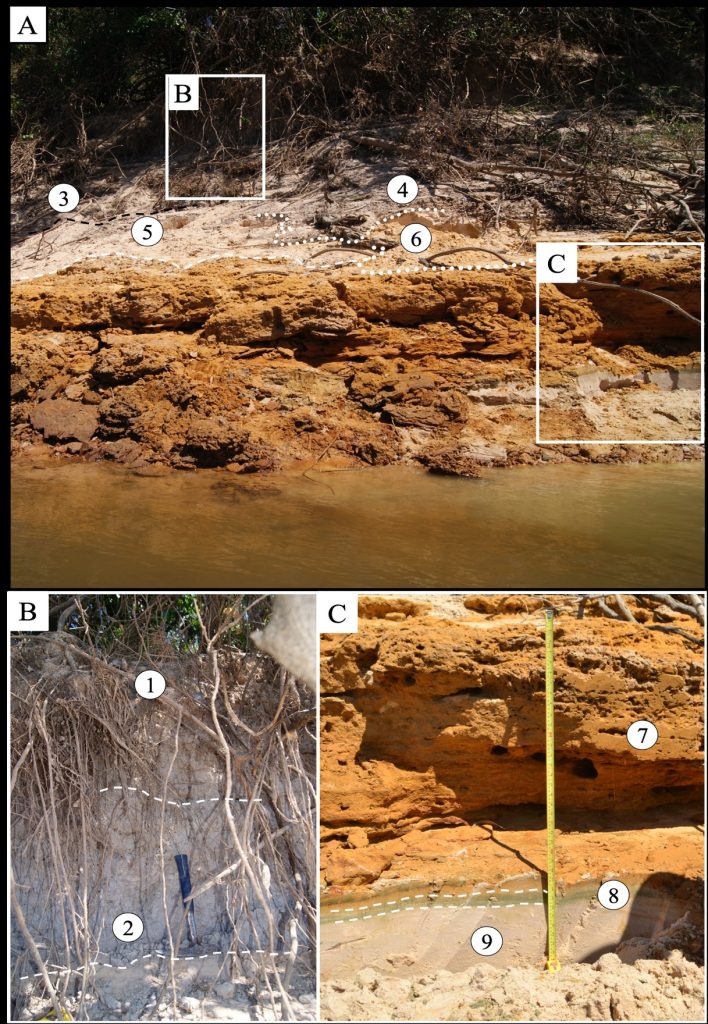

In the Coco Beach profile (Fig. 2) the lithological succession starts at the base from 513 to 475 cm depth, a pallid brown (10YR 8/3) medium sand, well selected, high sphericity and rounded grains, displaying a thin (15 cm of thickness), olive green (5Y 5/4) layer at the top (Fig. 2 C: points 9 and 8 respectively). From 475 to 410 cm depth, the sediments consist of strong dark brown (7,5YR 5/8) medium sand, well selected, however with low sphericity and sub angular to sub-rounded grains (Fig. 2 C: point 7), presenting quartz grains impregnated by iron oxyhydroxides. Between 410 and 360 cm, the material is a brownish yellow (10YR 6/6) medium to fine sand, moderately well selected, high spherical and sub angular grains (Fig. 2 A: points 6 and 5). In the interval from 360 to 345 cm occurs a brownish yellow (10YR 7/6) fine to medium sand, with solid and compact structure resembling a hardpan. It contains dark yellowish brown (10YR 3/6) and black (10YR 2/1) spots, moderately well selected, high sphericity and angular to sub angular grains (Fig. 2 A: point 4). From 345 cm upward, there is a yellow (10YR 7/6) medium to fine friable sand, moderately selected, high sphericity and rounded grains, some dark grains are present; a yellow to dark brown medium to fine sand moderately selected, high spherical and sub-rounded grains (Fig. 2 A: point 3). At 195 cm depth, the profile shows a light brownish gray (10YR 6/2) to light gray (2.5Y 7/2) silty clay loam showing strong dark brown (7,5YR 5/8) spots and presence of some roots and branches (Fig. 2 B: points 1 and 2). To summarize, the profile begins with a domain of medium-grained, light-colored sands in the lower beds, transitioning to medium to fine sands with strong dark brown coloration and a compact structure in the middle layers, and ending with a light gray silty clay loam at the top, which contains root traces. The grain size, sorting, and roundness decrease upward, reflecting a continuous reduction in the energy dynamics of the sedimentary environment.

On the other side, the thick iron oxyhydroxide impregnation in the intermediary section may support a relatively long-term position above the river water high level, the basic conditions for oxygen availability for iron oxidation and complex precipitation. This becomes more expressive at intervals of 345 and 360 cm in depth, where a quasi of hardpan can be recognized. It presents a yellowish-brownish sandy texture and dark yellowish-black and black spots. The fine light green zone found between 493 cm and 475 depths (Fig. 2C point 8), indicates a probable iron reduction, probably showing Fe2+ compounds (iron phosphate and/or sulphate) meanwhile a possible condition of stagnant water, just provided by the low to medium level of river water. The Coco beach succession may respond to quartz sand, probably a river point bar, which was strong and pervasive invaded by iron oxyhydroxides.

Figure 2. Lithological succession of the Coco Beach profile. A. General overview; B. Detail of soil horizon; C. Detail of reddish sand and of the thin olive zone. The samples of this material were collected in this river cliff exposition.

In the upper part of the Coco Beach profile a slight gray A soil horizon (Fig. 2 B) has already been established, covering a light grayish-brown B horizon with strong brown spots (mottling) and presence of branches and roots, whose activities developed cavernous cavities, which much more common because they stay just in front of the water river impact.

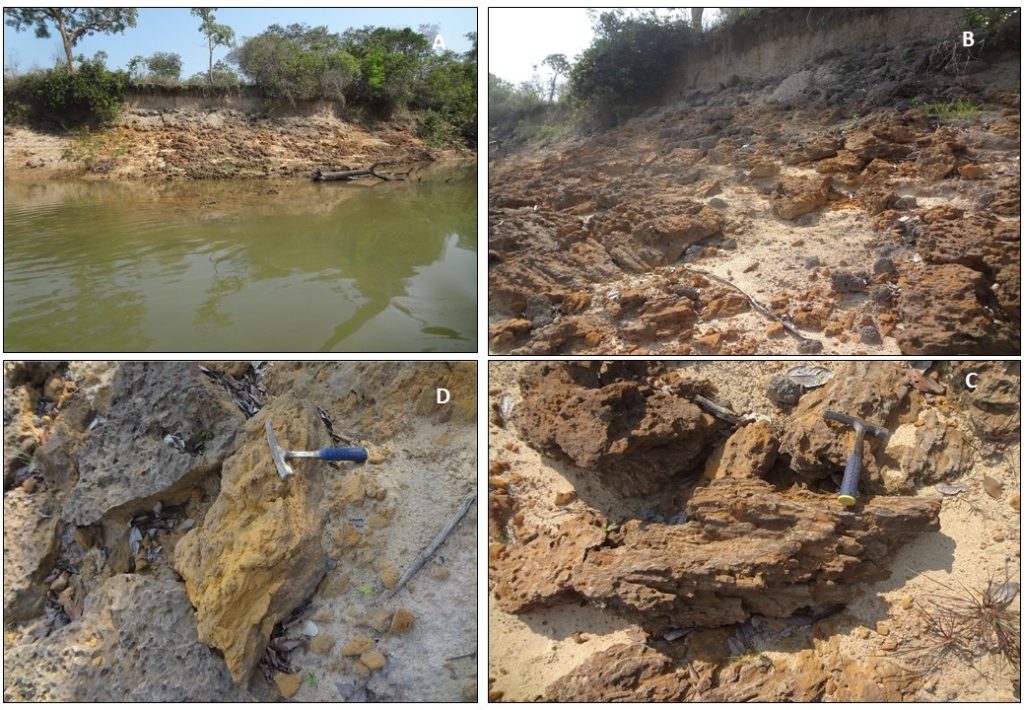

The sand of the river bar probably rose above the high-water level of the earlier river, became a body of water-table that ran for drainage. These waters drained neighboring areas and perhaps crossed the sandy body with iron minerals, mainly the oxyhydroxides, that in contact with the organic matter of the decayed forest with formation of humus and peat, dissolved these oxides, complexed them and the released iron, the which mediated by bacteria, oxidized mainly in the water table breaking in the paleo cliff, and precipitated around the quartz grains, originating the iron hydroxide fronts, which gradually cement the sands (Fig. 3).

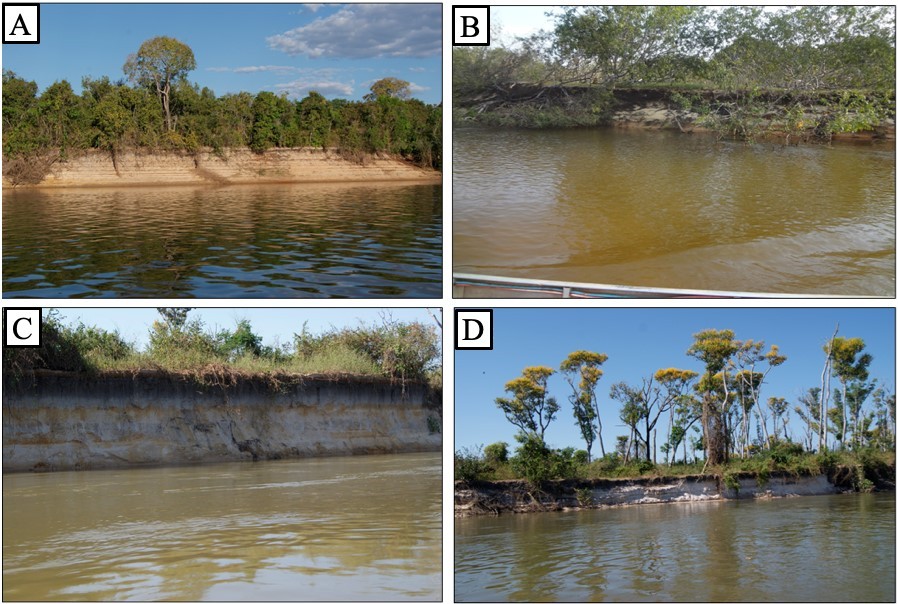

Figure 3. Typical older ferruginization (cementation of sand bar by goethite, mainly) and developing a sand-rich ironstone creating a condition to form river cliff pontoons. A: general exposition of ferruginized sands along river cliff or cliff pontoons; B: details of a thick and local ferruginized sand improving the stratification; C: details of these blocks; D: blocks showing tabular forms developed on the contact zone sand silt/clay (interface ironstone).

These features of older ferruginization found in Coco are common throughout the northern region of the Bananal Island. They are exposed in many places, especially on the cliffs in the lower course of the Javaés river, where clayey or argillaceous silt packets usually topped by black soils covering old sandy bars. The ferruginization may be later formations related to the flow of the water table and/or the crystallization of the iron oxyhydroxide colloids that cover the sands of the bars and flow laterally in the body of the bar. Valente et al. (2013) describe them as laterites; however, they are not in any way lateritic formations.

3.1.2 White Barrier

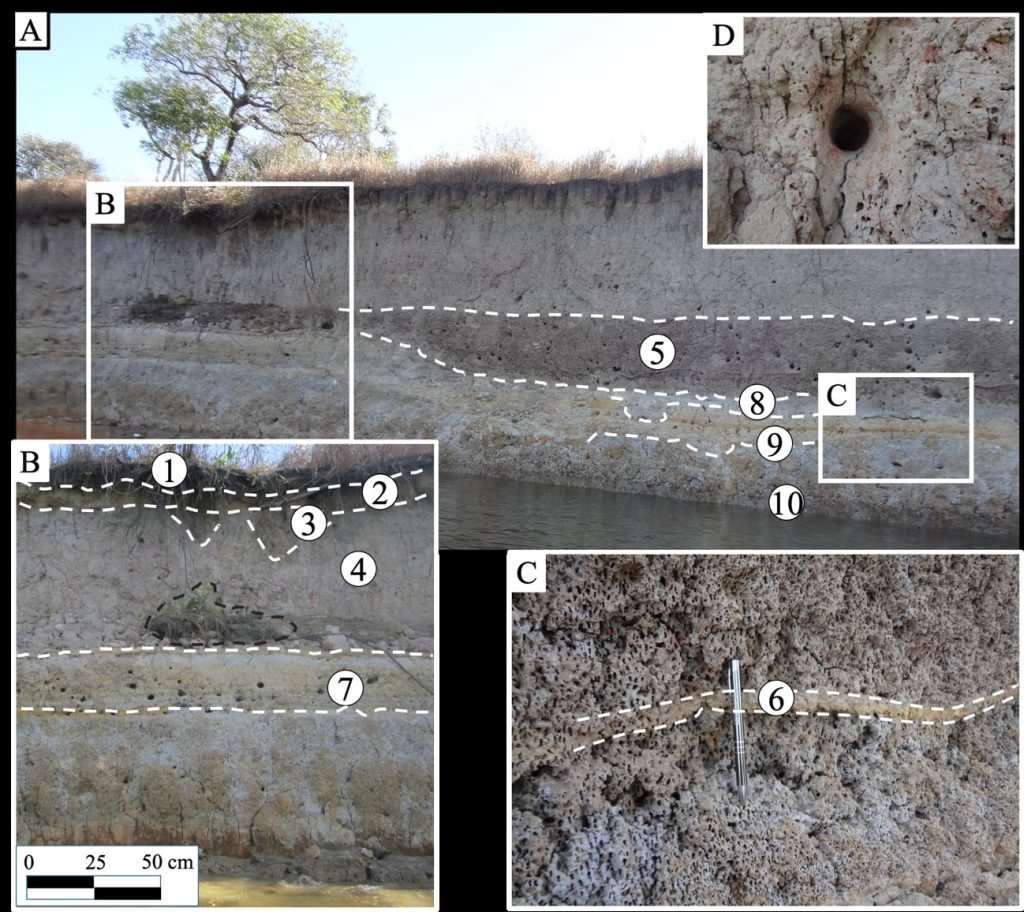

The lithological succession of the White Barrier (470 cm of thickness) comprises a light gray (2.5Y 7/1) clayey silt at the base, becoming whitish (2.5Y 7/1) upwards, showing some yellowish red spots (7.5 YR 6/8) as slightly mottled pattern (Fig. 4 A and B, points 10-4) some circular fish holes forming a cavernous structure (Fig. 5 C). However, the interval between 325 and 280 cm, it becomes a very hard aggregate packet (like a hardpan), very pale brown, stratified by color shading alternation, dominated by sandy texture, and much more fish holes (Fig. 5 A and B point 7). Immediately above, the layer of whitish silty clay, with yellow (10YR 7/6) and yellowish red (5YR 4/6) random spots, cavernous structure returns. Note in this point a very thin lens of yellow sand that becomes thinner and disappears along the sequence (Fig. 5 C, point 6). Upwards this sequence is whole composed of gray silty clay (2,5Y 7/1), slightly laminated, with large horizontal fish holes, easily breakable (Fig. 5 A, B: point 5). Locally appear undulations colored with a gray to green color marking an environment changing. Probably a paleo channel was fulfilled with floodplain sediments and reducing conditions have established on the basal contact. This gray silty clay packet converges upward into light gray whitish (5YR 8/1) silty clay, with slight randomly distributed yellowish red (5YR 4/6) spots, slightly laminated however with rare horizontal fish holes. Finally, the last 50 cm to the top of terrain surface established a typical young soil profile developed over the previous silty clay sediments. An olive brownish B horizon (2,5Y 5/4) silty clay loam from 50 to 20 cm in depth, with a massive structure with root activity and plenty of vertical fracturing (dehydration by sunstroke fracturing) that in part reaches the underlying layer and are partly occupied or developed by plant roots. (Fig. 5 A and B). It´s followed by a grayish brown (2,5Y 4/2) thin A horizon from 20 to 10 cm in depth, silty texture, crosscut by roots and vertical fracturing and on the last 10 cm the A horizon, dark gray and silty, whereby the vertical fracturing The soil profile becomes very remarkable and impressive by the development of well-formed columnar disjunctions is much more intensive. Grassland with some dispersed shrubs and trees covers the terrain.

Figure 4. Lithological succession of the White Barrier profile. A. Overview. B. Detail of the White Barrier. C. A detail of the thin brownish silt layer. D. Detail of horizontal circular fish hole developed in the mottled clayey silt showing the cavernous pattern.

Figure 5. Lithological succession of Collapsed Ravine profile showing in general a whitish friable fine sand on the bottom (5 and 4) followed upward by a black organic-rich sand (3), correlated to a spodic horizon B, and then a pallid gray, little organic and sandy (2), the E horizon and finally at the top and thinner organic-rich with roots and plant debris, A horizon (1).

3.1.3 Collapsed Ravine

Four units were identified in the profile of Collapsed Ravine in Araguaia River (Fig. 5): at the lower part, 300 to 150 in depth, a thick white (10YR 8/2) homogeneous massive in the lower part (Fig. 5 number 5) being friable and showing locally some cross stratification (Fig.5 number 4) to the middle and upper part, which display some aggregates of light brownish gray (10 YR 6/2) sandy clay. It´s followed, from 150 to 100 cm in depth, by black (5 YR 4/1) sand rich on fine organic complex material (Fig. 5 number 3), slightly compact, showing a light appearance of hardpan. A pallid black (10 YR 4/1) sandy horizon (Fig. 5 number 2), from 50 to 30 cm, established upward with irregular contact with the previous one (Fig. 5 number 3) and finally a thin dark (10 YR 5/4) unit (Fig. 5, number 1) carrying some humus, from 30 cm to land surface. This succession can be well correlated to a classical spodic profile, being unit 3 the spodic horizon B and unit 2 the (eluvial) horizon E and the unit 1 the A.

3.1.4 Canguçu Harbor

The sediment cross section along the Canguçu Harbor shows locally a yellow (10 YR 7/8) sand basal unit, reaching a deep from 590 to 425 cm (Fig. 6A points 7 and 6), with cross bedding and parallel stratification, which is overlain by a thick unit (from 425 up to 85 cm) composed by silt and clay, being normally silty on the lower part (Fig. 6A point 5) and clayey silt on the upper parts (Fig.6B points 4 and 3). This sediments packet presents whitish (10 YR 8/1) changing to very pale brown (10 YR 7/3) coloration between 143 and 85 cm (Fig.6B point 3). This clayey silt to silty clay unit displays pale shades, sometimes presenting a yellowish red (5 YR 4/6) mottling, or massive structure and some fish holes, what are very frequent in this region.

The upper material with 85 cm thick ((Fig.6B points 2 and 1) is composed of clayey silt gleysol horizons A and B which occupies continuously the terrain surface and becomes very evident. The soil horizons are rich in roots and root perforation with a coloration ranging from dark grayish brown (10 YR 4/2) to light brownish gray (10 YR 6/2) much like the geological section of the White Barrier, which is located to the northwest of Canguçu.

Figure 6. Lithological succession of Canguçu Harbor profile. A: Western view; B: Eastern view; C: Detail of the green massive clay loam deposited over the sand bar and involved by clay silt upward and laterally; D: Lower zone of horizon A of the silty gleysol, light gray, showing the typical columnar feature, with presence of roots, in gradational contact with the silty clay layer. A characteristic pattern of these soils along the northern part of Bananal Island.

In detail detached by the profile just on the Canguçu harbor one can observe lateral and vertical changing in the spatial distribution of silt and clay, as well as the mottling parties. Similar to what has been described in other sections in the Canguçu Harbor, sands of bars with flat-parallel stratification, also crossbedding (Fig. 6), appear to be friable, stained yellow. On them silty clays were deposited with green clays (type lenses), which at the top assume a silty clayey nature with great lateral extension. In the contacts between silt and clay and between clay and sand is common the occurrence of yellowish areas, stains of iron hydroxides. At the top the clay silt layer gradually passes to a continuous horizon of dark gray, slightly columnar soil, gleysol (Fig. 6), as White Barrier. It stands out in the inferior and superior contact zone, the yellow to ocher ferruginous impregnation, that occurs nowadays on the beaches of Javaés river, that tends to be reddish. Possibly the green clay may correspond to a deposition in the common depression in the river sandbar zone. The columnar feature, with presence of roots, in gradational contact with the silty clay layer is a characteristic pattern of these soils along the northern Bananal island.

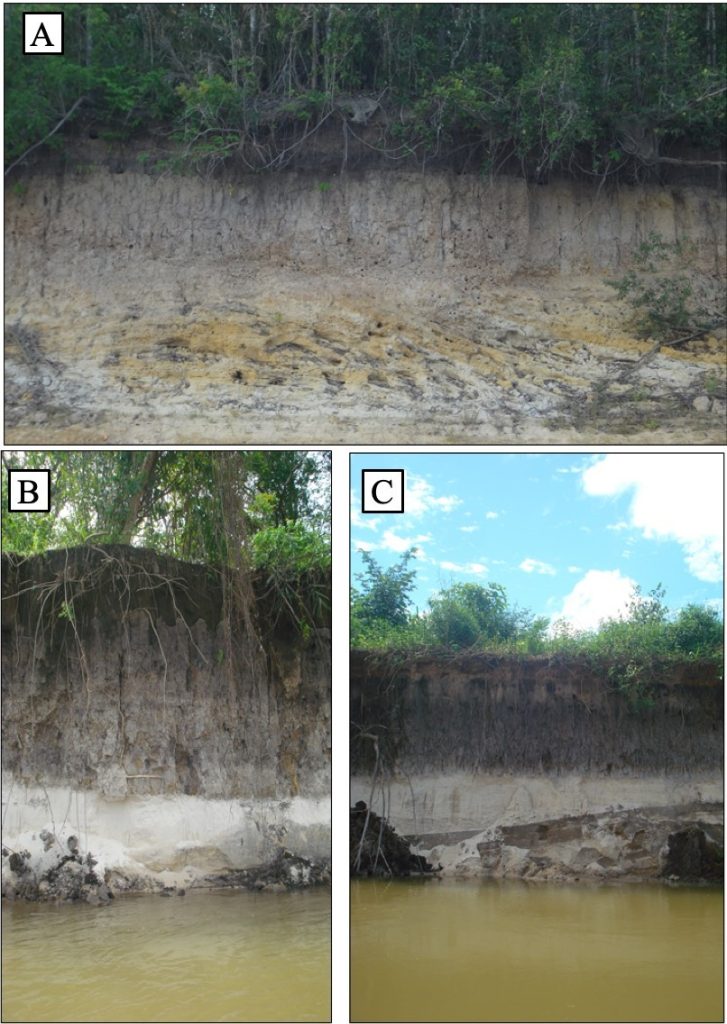

- The Spodosols to Gleysols

The presence of gley to spodic soils north of Bananal Island is striking (Fig. 7), and is usually associated with a sandy substrate, either alone or deposited on a layer of silt and/or silty clay or direct on clay deposited over sand (Fig.8). They discriminate against very flat, generally still slightly lowlands, in which the grasses stand out, but also form substrate of areas of shrubs or dense forest, this is less frequent. Sand substrates generally represent riverbanks attached to each other and are vegetated initially by grass in this region.

The north of the Bananal Island stands out for the almost continuous occurrence of a horizon of gray soil, dark gray to black on its surface, with thickness ranging from 30 to almost 200 cm thick as already presented in Coco Beach (Fig. 2), White Barrier (Fig. 4), Collapsed Ravine (Fig. 5) and Canguçu Harbor (Fig. 6). The tonality is, as in most soils, given by the abundance of humus organic matter, as well as woody fragments and leaves mineralized. Normally it is silt-sandy to clay-silty. Its contact with the sediments below varies from gradual to abrupt, which may be mottled or not. A strong aspect of these soils is the tendency to present vertical columnar disjunctions, from pentagonal to hexagonal cross-section, which extends weakly to the sediments below. These columns however occur only when the nature of the silt-clayey soil. Vertical fractures accompany columnar disjunctions, just as pivoting roots are frequent and reach the lower layers just below. They suggest a long time of drought, leading to dehydration, which occurs in slightly clayey soils, where the clay mineral is at least in part 2:1.

Figure 7. Distinct aspects of forests established over different stages of gley to spodic soil formation over sand river bars in the northern Bananal island. A: An already vegetated young river bar starting the development of probable gleysol; B: partly river eroded old river bar with sandy gleysol; grassland and shrub dominate. C: Also, a typical gleysol over white sand river bar occupied by forest and grassland. D: Another typical gleysol showing a reducing condition (E horizon) and starting to form the B horizon for future spodic soil (yellowish iron hydroxides fronts).

Figure 8. Three distinct occurrences of the dark soils (Gleysols) in the land surface in the Northern Bananal Island. A. Dark soil A horizon formed directly over the clay silt layer, vertically fractured, columnar. B. Dark gray soil A horizon formed from new sediment deposited over white sand. C. Another gray A horizon, compact, vertically fractured, columnar, already obliterated by young flooding sediments, formed directly from clay deposited on sand.

These soils, however, formed on different substrates or derived from them (Fig. 8). Of particular interest are those that formed directly from old floodplain clay-silt sediments (Fig. 8 A), or those that developed on silt sediments deposited through erosion over older mottled clay-silt sediments (Fig. 8B and 8C), or on sands from young to old bars. The sandy black soils lack the columnar structure characteristic of the clay-silt soils.

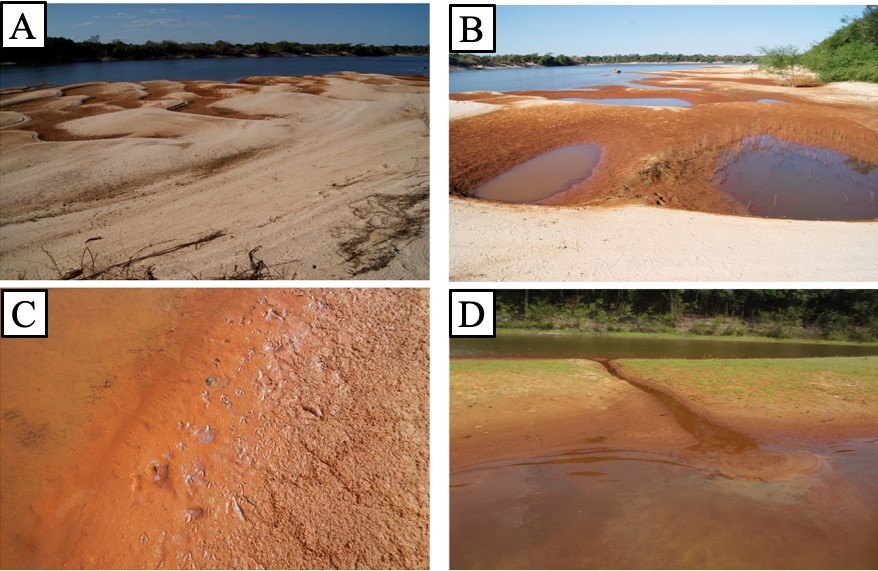

- The Reddish Film (muddy lamina) at Long Beach

A very striking feature during the drought period of the Javaés river are the long, sometimes undulating, yellow to brown sandbars (river beaches), with sub circular ellipsoidal depressions, contoured by red rather than reddish films (Fig. 9), which extend to the water level of the river. They also cover the bottom and margin of the depressions, giving them a very special coloring. At the depressions the brown sandbars tend to be thicker, taking on the appearance of iridescent muds, full of small-to-large bird footprints, as well as feathers and much excrement. All in all, they describe an image of rare beauty. Locally this fine reddish iron oxyhydroxide complexes in mm thick can be found centimeter deeper in sandy bar cementing the quartz grains in different parallel levels. In depressions it is common to find a grayish green zone just below the red muddy film, which has a strong, sulfurous odor corresponding to a possible reduction action of iron hydroxides and accumulation of organic matter and its mineralization. The red film and sandbar interface, the substrate of depressions, is an oxygen-poor environment, due to the non-renewed water and the activity of birds, fish, which are consumed by the birds, excrements, bones of these animals, and at the end lead to the formation of a reducing microenvironment, something like a eutrophication.

Figure 9. The reddish films or reddish thin, muddy lamina on the sandy bars of the Javaés river. A. corrugated bars contoured by red films, in the same way their depressions covered by these films and muddy lamina; B. Well-developed depressions bordered by surficial red films and red muds in their interior. C. It shows the red mud on the contact zone between sand bar and the lagoon water and prints of bird movements are engraved in the mud. D. Canal interconnecting a small circular lagoon with the Javaés River, transferring red mud from this to the river. The sand of the boundary bar is impregnated with the same red complexes as the films.

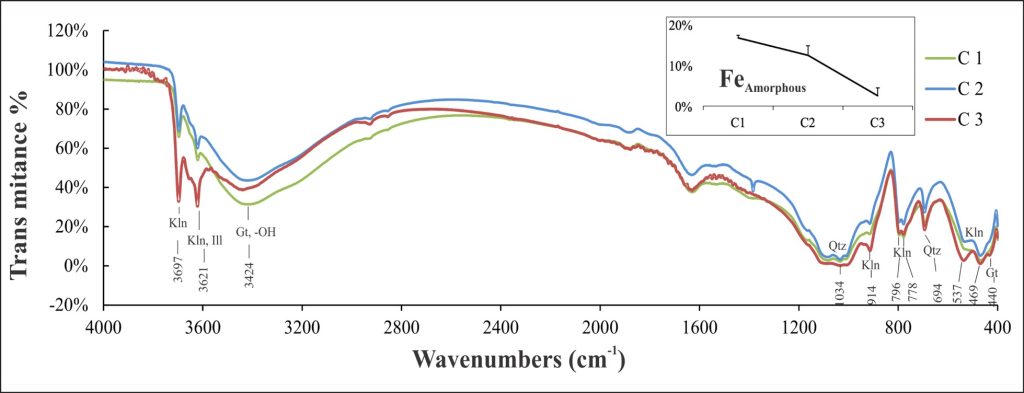

Figure 10. FTIR analyses of red films (red gel) and green zone (green gel) from Long Beach, showing the possible sample mineral composition, as well the content of amorphous iron (Feamorphous).

The superficial red film converges to a thin red zone within which the quartz grains are surrounded by red films which converge to a grayish green (gley) zone below, and gradually to the bar sand. The two zones together generally vary from 4 to 8 cm thick. This pattern can be observed in most sandbars along the Javaés river.

The red color of the films and red zones is given by colloidal complexes consisting of iron oxyhydroxides whose formation was mediated by bacterial actions on the surface of the sands and in the first cm of depth, as the water level of the river goes down. The resumption of water level rise may partially or completely destroy the products of this process. But on the other hand, the deposition of a new layer of sand may favor partial preservation.

The red film complexes are amorphous to XRD, with the exception, obviously, of the quartz grains present. However, by FTIR it was possible to identify bands related to clay minerals equivalent to kaolinite, goethite and possibly illite (Fig. 10). The sample (C3) of greenish-like gel shows a slightly different pattern, which was to be expected, the other is reddish-like gel, with the much stronger 3697 and 3621 bands, likewise at 914, 696, 537 cm -1 bands. Iron is not present as a ferric hydroxide, but possibly as an amorphous ferrous complex, responsible for the green color. The content of iron (amorphous) (Fig. 11) is 16.7% for sample C1, 12.5% for C2, both represented by red gel and 2.5% for green gel, which confirms the expressive presence of iron in red and greenish gray complexes (gley) but decreases in depth.

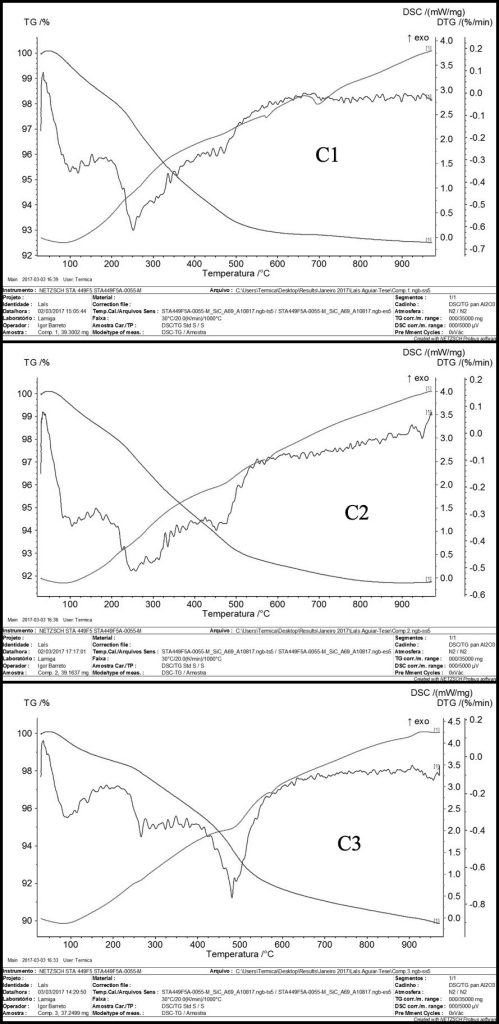

Figure 11. Thermal analyses of the red and green gel from red films and red and green zones.

The thermal analysis shows that the samples of red films C1 and C2 have a similar thermal behavior in TG, DTG and DSC (Fig. 11), so they resemble each other, as demonstrated by the FTIR analysis. The DTG curves allow us to identify three important thermal events, around 112º C, 250ºC and 460ºC, perhaps at 950ºC in C2. The events at 250°C and 460°C are represented by slightly greater mass loss (TG curve), although in general the mass loss gradient is accentuated and almost continuous until about 500°C, when it then becomes smooth and continuous until near 900°C. Loss of water of amorphous material (Fe oxyhydroxides and amorphous opal in diatoms) is allowed, non-structural, compatible with the physical state of gel (colloid). Changes in physical states appear to have occurred at 250°C (very subtle), 573°C and 725°C (C1 only), representing the possible structural ordering of the ferric colloid in goethite/lepidocrocite, the displacive polymorphic transformation of quartz α (low temperature quartz) to quartz β (high temperature quartz) or opal to quartz, and metakaolinite, respectively. The endothermic peak between 975 and 1000°C in C2 seems to indicate the transformation of metakaolinite on the way to mullite formation.

The DTG curve for sample C3, colloid or gray green gel shows endothermic events at 90ºC, 265ºC (irregular and subtle, unlike C1 and C2), 480ºC, 573ºC and 950ºC, respectively representing changes in mass loss gradients, the strongest at 480°C. The DSC curve shows transformations at 90ºC, subtle at 265º and clear at 480º, 573ºC and 925ºC, the same transformations of C1 and C2, but with clear formation of mullite at 925ºC. At 265ºC it seems to indicate the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, which diverges from C1 and C2.

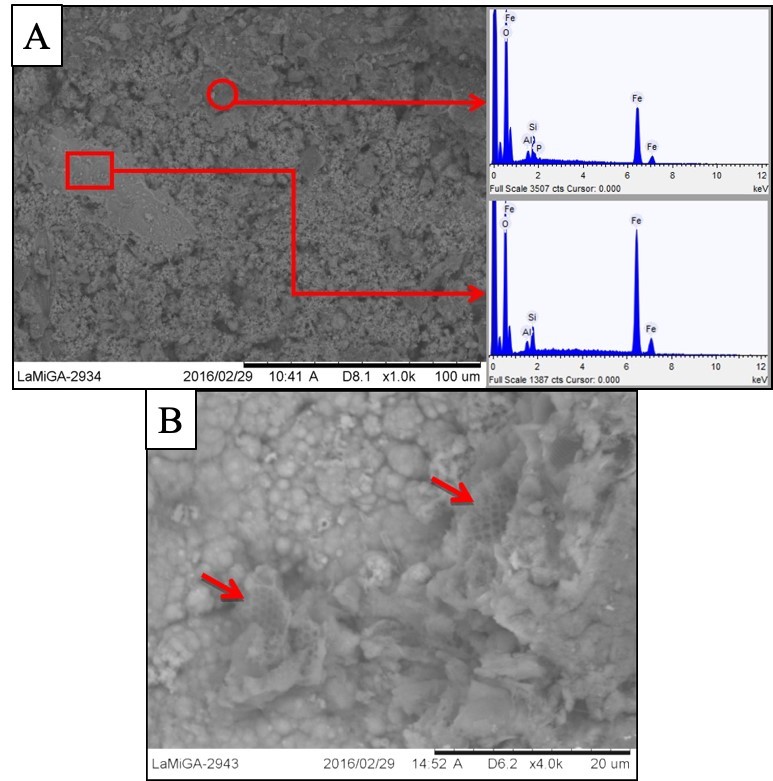

In the red gel C2, like C1, the chemical analyses obtained by SEM/EDS demonstrate the domain of O and Fe, while Al and Si are in less quantity, as red film involving the quartz grains and also as whole gel material, besides the presence of P (Fig. 12A). The domain of O and Fe characterizes the presence of iron (oxyhydroxides), as indicated by FTIR, however amorphous after XRD. The parallel pattern of Al and Si, side by side, in the EDS spectrum suggests the presence of kaolinite structure, but the more elongated asymmetry of the Si peak also recommends the presence of quartz or amorphous silica, such as diatoms (Fig. 12B) very frequently. The presence of diatoms indicates a high relative concentration of soluble silica in the river waters. Phosphorus occurs locally, to a lesser extent, then by the presence of Fe and O, it can consider as possible amorphous iron phosphate, type vivianite, or a precursor of this mineral, as was established in Coco Beach.

Figure 12. A: SEM/EDS analyses of the red film or gel around the grain materials (minerals and organic) and of the cement showing the domain of O and Fe. B: Several diatom fragments in the red gel (red arrows).

3.4 XRD Mineralogical Composition

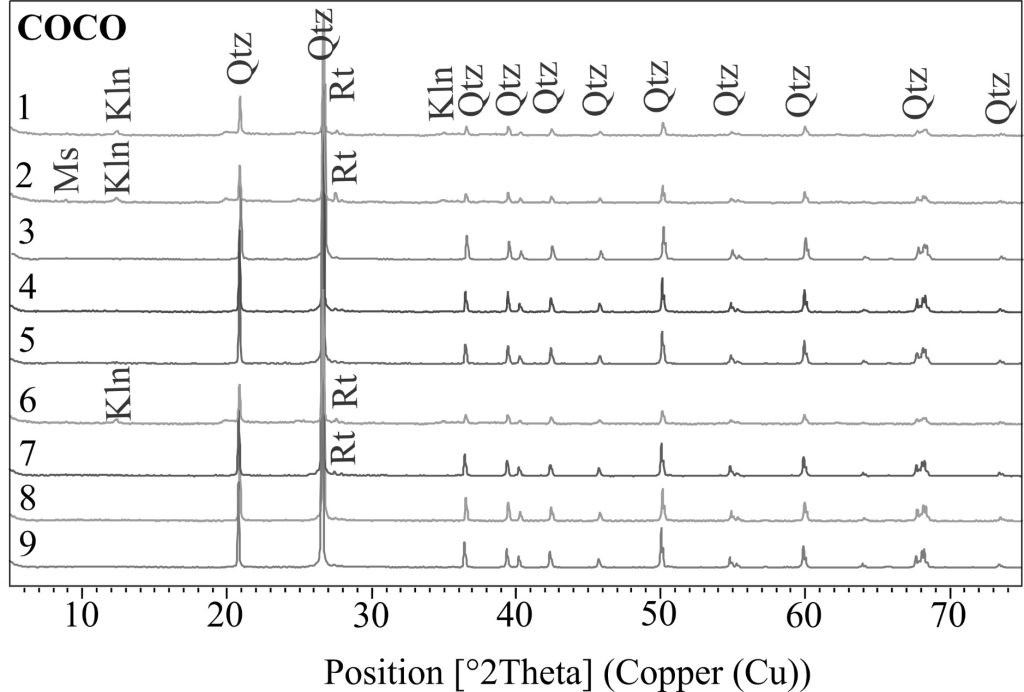

The XRD results of Coco Beach sediments (Fig. 13) showed mainly the domain of quartz, being kaolinite and illite/muscovite as accessory minerals in the clayey sediments and soil, rutile may be also present as accessory mineral.

Quartz is also the main mineral of White Barrier being kaolinite and illite/muscovite, however much more abundant than Coco Beach and probably rutile. Kaolinite occurs in all the samples, being more frequent of course in the clay silt.

The main minerals which constitute the sediments of Collapsed Ravine are quartz, kaolinite and illite/muscovite, and probably rutile. The clay minerals become components of the probable B spodic horizon.

Again, the main mineral constituent of the sediments of Canguçu Harbor is quartz; illite/muscovite and kaolinite, which is much more frequent, and probably rutile, similarly to Coco Beach and White Barrier. The sand layer is only constituted by quartz after the XRD data.

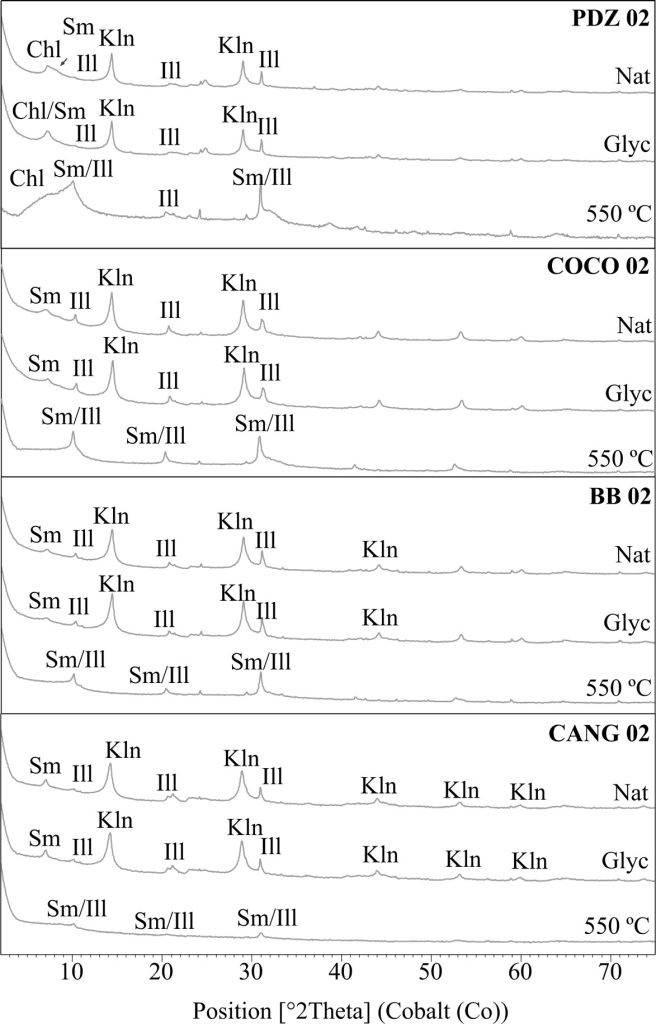

The mineralogical analysis of the clay fraction of each sample investigated by X-ray diffraction, on a glass slide, under natural conditions, glycolated and heated to 550ºC, allowed to better characterize the clay minerals (Fig.14). These analyses confirmed the presence of the minerals already demonstrated and allowed them to show the presence of smectite and seldom chlorite. The abundance of kaolinite, present in most non-sandy samples, was similarly clear, as did the illite/muscovite as the second most abundant clay mineral. Smectite has been identified in clay fraction of most samples in all geological sections investigated, even in the fine sand spodic soil profile. This mineral contributes to develop the columnar disjunctions, very common in the dark gray soil A horizon. Chloride was identified only in the fine sand spodic soil profile, which is very surprising.

Figure 13. X-ray diffraction pattern from Coco Beach Profile (Coco). Kln: Kaolinite, Ms: Muscovite, Qtz: Quartz, Rt: Rutile.

The mineralogical constitution of all the geological sections investigated, sediments and soils is simple, dominated by quartz, in which kaolinite, illite/muscovite and smectite, rarely chlorite, make up the clay fraction of silty sediments and fine sand.

Figure 14. X-ray diffraction pattern of clay minerals from Coco Beach Profile (COCO), White Barrier (BB), Collapsed Ravine (PDZ) and Canguçu Harbor (CANG). Chl: Chlorite, Sm: Smectite, Ill: Illite, Kln: Kaolinite. Nat: natural, Glyc: glycollated, 550 ºC: heated to 550ºC.

3.5 Chemical Composition

The sediments and soils of the Bananal Island show a strong variation in the contents of chemical components which are basically represented by a few: SiO2 (37.5 to 99.5%), Al2O3 (0.35 to 19.4%), Fe2O3 (0.67 to 5.88%), K2O (0.08 to 6.6%) and TiO2 (0.05 to 1.5%). The contents of MgO (< 0.68 %) and P2O5 (<0.33 %) are low, however not negligible and of CaO, Na2O and MnO very low, below 0.19 % (mostly < 0.11%), 0.27% (mostly < 0.13), 0.05%, respectively.

This large variation in the oxides content of the major and minor elements, which was expected after the grain sizes (sand and clayey silt), very well depicts the variation of quartz sands, which normally constitute the riverbanks, as substrate of the silt or clayey silt sediments of flood plains, besides the dark soil horizon rich in organic matter and clay minerals. These latter carriers of clay minerals, such as kaolinite, illite/muscovite and smectite, that constitute the silt-clay fraction. The high levels of LOI determined in the soil samples depict the high content of organic matter (humus) of these materials. The relatively higher contents of Al2O3 and SiO2 are clearly responsible for kaolinite, and for illite/muscovite, highlighted by K2O, and also smectite, which is strengthened by the determined Fe2O3 (in part), MgO and CaO. Some relatively high contents of K2O indicate that illite/muscovite can be abundant as well those ones of Al2O3 for high contents of kaolinite and/or smectite, when K2O is low level. These chemical aspects are very important because X-ray diffraction analyses tend to give an idea that these clay minerals are in small concentrations, which is not true, they can reach high concentrations in silt sediments. The relatively high iron contents do not respond to crystalline iron minerals (not identified by XRD; however, by FTIR) but are correlated with the spots and with the ferruginizing fronts, therefore considered to be amorphous iron oxyhydroxides.

The distribution of the contents of the major and minor elements throughout the investigated sections show in general terms similar patterns (Fig. 15), especially in those of Coco Beach, White Barrier and Canguçu Harbor. The decreasing levels of SiO2 and increasing Al2O3, Fe2O3, K2O, among others, faithfully depict the quartz sand substrate and the silt and silty clayey sediments overlapping, and LOI at the top the domain of dark soil rich in organic matter. This behavior is also presented in the sand profile with gley or spodic type soil. It is practically possible to conclude that the SiO2 contents are in opposition to the other major and minor chemical elements, in a negative linear or linear tendency correlation, that is, quartz against the clay minerals. And two groups of samples according to the chemical composition are also recognized: high silica/low aluminum + alkalis and low silica/high aluminum + alkalis, respectively, sands and clay silt, river bars and floodplains.

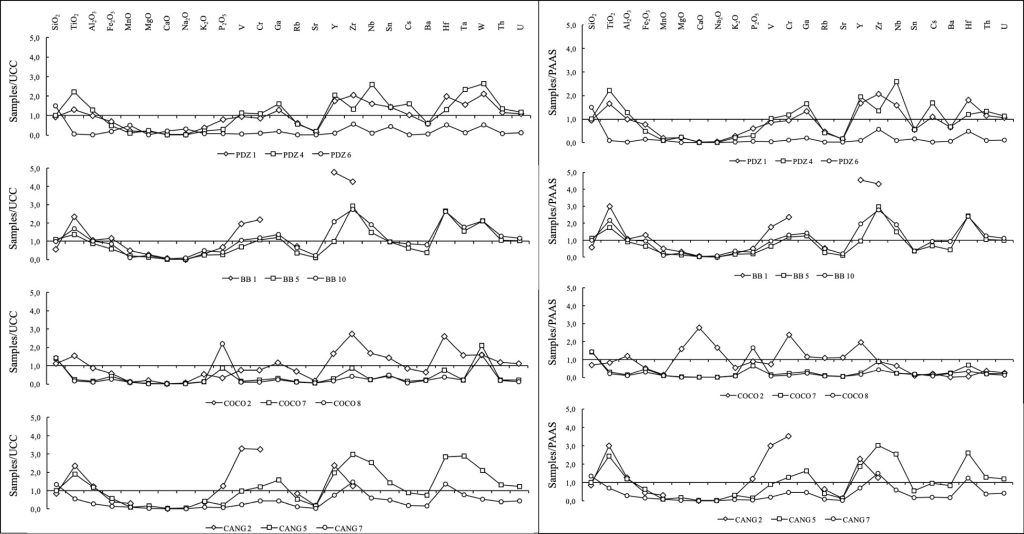

The chemical contents of the analyzed samples when normalized both the chemical composition of the Upper Earth’s Crust and the PAAS (Fig.16) sediments show that the sediments and soils of Northern Bananal Island are impoverished in almost all elements.

Figure 15. Distribution of the concentrations of SiO2, Fe2O3, Al2O3, MgO, TiO2, K2O and lost on ignition (LOI) along the sediment and soil profiles of Coco Beach (COCO), White Barrier (BB), Collapsed Ravine (PDZ) and Canguçu Harbor (CANG).

Figure 16. Chemical concentrations of investigated samples (Collapse Ravine, Coco Beach, White Barrier and Canguçu Harbor normalized to UCC and PAAS.

If, on the other hand, we confront the silt to clay with the sandy sediments, it is clear that the clayey ones are enriched in all analyzed elements, except SiO2. Therefore, clay minerals and amorphous iron hydroxides are the main mineral carriers of the chemistry of these materials, but the levels are below the PAAS values and the crustal average.

4 DISCUSSIONS

- The establishment of river point bar and floodplains: from Medium Holocene to Actual

The geological and sedimentological data in the investigated sections in the northern region of Bananal Island allow us to recognize that it was the scene of meandering river channels with its marginal dikes and extensive and broad floodplains established already in the Holocene as shown by Mendes et al (2015) and (2024). This extensive plain in the Late Holocene seems to be resumed by a new meandering river system, with the formation again of marginal dikes and broad floodplains and oxbow lakes or lakes between point bars (closed channels). Irion et al. (2016) on the other side already identified three flooding units: active floodplain, active paleo-floodplain and inactive paleo floodplain. As shown, these three units are not so evident in the north of Bananal Island.

The sediments are dominated by sand deposited in bars and channels, silts on the river dikes and silt clay to clay in floodplains and in small depressions formed in the lateral evolutions of the bars. This development can now be observed in this region. The present rivers, especially the Javaés, are sculpting the previous river sediments and their floodplain sediments and from their constituents form new bars, in general, colored horizontally and superficially by gels of iron oxyhydroxides, which present itself as a very characteristic and beautiful feature. These activities occupy the entire area and are responsible for the immense seasonal wet to dry lowland, which characterizes the northern portion of the Bananal Island. This land formed from riverbanks extends inland, not yet vegetated, or only along the low sutures between them, while in the lands on the right bank of the Javaés river, similar bars, perhaps a little older, with lakes and “paranás” (river channels between sandbars) transformed into lakes, are already fully occupied by dense young forest. The morphology of these bars may be related to mid-channels to point-bars, typical for river of low discharge and meandering. The actual channels of Javaés and Araguaia rivers are reworking these already deposit and not completely vegetated young fluvial sediments.

- Older ferruginization of sandy point bars

The sandy sediment bodies or in contact between these sediments and the silty in the recent past was reached by intense ferruginization (formation of red iron oxyhydroxides), which partially cemented the quartz grains of the sands, giving a crust appearance, and still stained the sandy body in the zone of contact with the silty ones. These fragile crusts partially support the cliffs. This ferruginization goes back to the oscillation of the fluvial waters during the drought and of the water table and does not represent lateritization processes. Similar processes will be observed in the young and actual river point bars. This is another quite distinct aspect of the investigated region.

- Erosion and sedimentation (Fluvial and lacustrine)

According to the data obtained, the low flat plain of the northern portion of Bananal Island represents an active system of lateral erosion and sedimentation river to fluvio-lacustrine, as already identified by Latrubesse et al. (2009) and Valente and Latrubesse (2012) on the island, although apparently older. The Javaés River apparently settled on ancient river sediments deposited also on long plains. Different types of bars, from small to large extensions are established along the riverbed, which in their lateral evolution give rise to lakes between bars and at the time of flooding partially cover the previous gleysols, in a new phase of floodplain lowland sedimentation.

- Modern ferruginization

The red-stained sands of the river bars at the current points, markedly in the Javaés river, besides constituting a beautiful visual scenery, represent a new event of ferruginization of these bodies during the low-level season of the waters of that river. The gel aspect, rich in amorphous iron oxyhydroxide complexes, show the very young nature of the same, and contrary to the previous condition, they still do not cement, but only stain the grains and create a moist mass around them. Some depressions within the bars accumulate more of these gels and create an underlying reducing environment. Indicative of the reducing conditions is the presence of ferrous minerals such as vivianite (inferred), which readily forms in the depressions, which are the scene of animal life (fish and birds), which add to these waters P and C coming from the dissolution of their excrement and bones. Therefore, a resumption in a short period of time, without involving rock alteration, as with laterite weathering. These iron gels demonstrate the high concentration of iron in the fluvial waters of the region, which drain the oldest rich bodies in that element, and at the same time a new phase of iron enrichment in the sand body. Iron rich rocks (laterites) are common in the neighboring region (Valente 2007) and may be iron source for these ferruginization. The formation of iron oxyhydroxides and gleysols and of slightly mottling demonstrates that the northern part of the island cannot be characterized as a typical wetland, but with low, flat terrain, with great contrast in water availability, droughts and floods.

- Vegetation soils and sediments relationship

The vegetation diversity north of the island is clearly controlled by the mineralogical, particle size nature and age of the substrate, and the time of contact with river waters (seasonality and flood zones). Grass occupies the quartz sandy banks, the margins of lakes and channels, and semi-evergreen and evergreen marshes. Its persistence contributes to the accumulation of organic matter and formation of organic soil, and below this the gleysol and same times a little bit spodic soil. In areas occupied by floodplain sediment, clay silt and silt clay, with the presence of clay minerals (smectite and illite, sometimes chlorite, which may release Mg, Ca, K, Si and P for the soils), and therefore higher fertility, medium-sized forest is rapidly developing since unaffected by long flood season. Valente et al. (2012) associated the floodplain with gallery forest, that occurs along of the inner rivers of the Bananal Island, which contributes significantly to the maintenance of the region’s biodiversity. Availability of water and high concentration of nutrients associated with the portion of internal relief of the floodplain, allow the development of gallery forest. This unit develops from sandbanks, where they are colonized by Myrtaceae and continue to increase in size according to seasonal floods, consequently the gallery forest is expanded.

- Weathering and Sediment Provenances

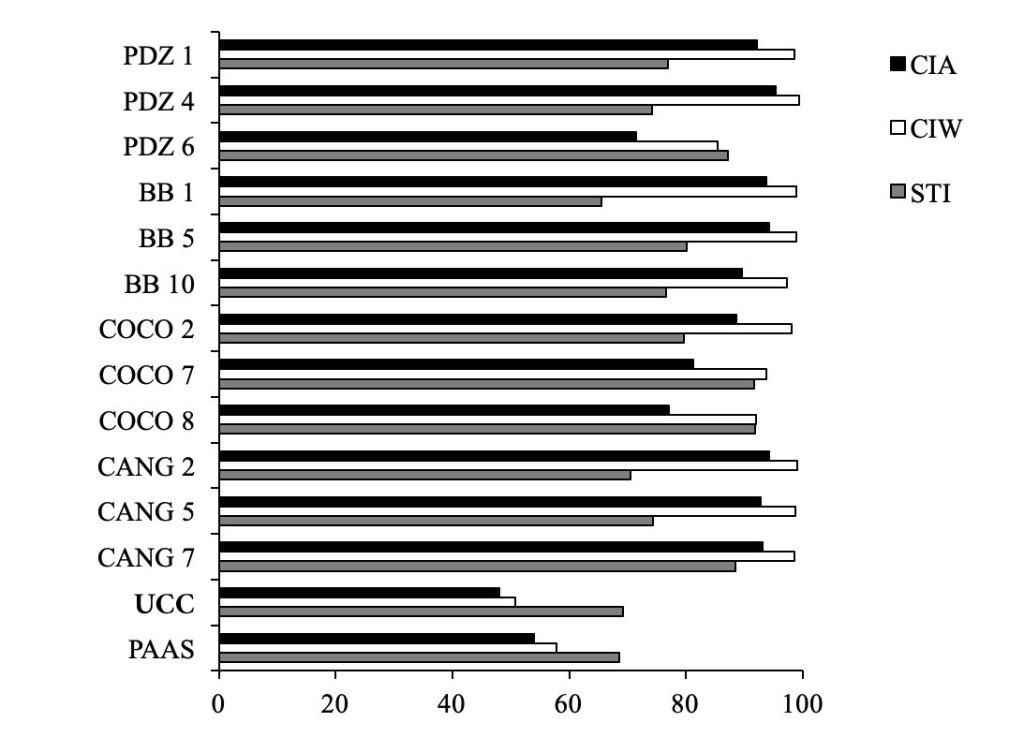

The mineral and chemical composition of the sand and clay sediments on the north of the Bananal island, dominated by quartz, or quartz and kaolinite, besides illite and smectite, rutile as accessory, however, minerals of Si, Al, Mg, Ca, K, and Fe, show a provenance from acid rock composition submitted to deep tropical weathering. Similarly, trace element concentrations including REE confirm the affiliation with acid rocks and their distribution controlled primarily by the clay minerals typical of the tropical zone. The comparison between various chemical alteration indexes (Fig. 17), calculated for these sediments and soils and for some reference standards, such as those of the Earth´s upper continental crust (UCC) and Post-Archaean Australian Shale (PAAS) (Taylor and McLennam 1985), confirms the high degree of weathering that materials underwent in relation to these same standards. However, with average values of CIA (Chemical Index of Alteration) around 97 and CIW (Chemical Index of Weathering) around 89. The STI (Silica-Titania Index), developed specially to measure the degree of weathering of metamorphic rocks, presents an average value of 78, that is corroborating to the chemical alteration of the studied sediments.

The great variation in the chemical composition in the sediments and soils reflects the grain size (sand for quartz domain; silt and clay for quartz plus clay minerals), and therefore the energy of the water drainage. Normally the sand domains at the base of the profiles and of silt and clay with organic matter at the top. The chemical stratigraphy observed in the sediments of the trails is mirrored by the decrease in SiO2 values and increase of Al2O3, MgO, CaO, K2O and LOI (mainly organic matter) towards the top (Fig. 17).

Figure 17. Distinct weathering indexes (CIA, CIW and STI) applied to analyzed sediments and soils at Northern Bananal Island.

- Landscape evolution

The data obtained in the geological sections investigated north of Bananal Island show that this region, probably in the Middle Holocene, was a meandering river scenario, with intense erosive and sedimentary lateral activity over a vast plain, and apparently with poor vegetation cover.

Probably this dense drainage network already reworked sandy, silty and clayey sediments, which in addition to quartz contained clay minerals such as kaolinite, illite/muscovite and smectite, perhaps iron oxyhydroxides. The presence of silica and soluble iron complexes is indicated by the systematic presence of diatoms and ferruginous red stains and cement. It is very likely that part of the smectites and chlorite are newly formed in situ due to the presence of these components (silica and Fe) and Mg and Ca in river water, probably.

In turn, it is very likely that almost the entire fluvial region has become a marshy grass forest-occupied environment by indicated by the almost continuous gleysol cover of dark, sometimes spodic nature, organic soil that reaches up to 1 m in thickness, a typical wetland. This material is tempted to contain chlorite and smectite and to be enriched in trace elements as well. This landscape promoted vert likely neoformation of smectite and chlorite and dissolution of iron oxyhydroxides e consequently the yellow iron front and spodic soils. Finally, in the Late Holocene the gleysols experienced a relative long term of drying represented by vertical fracturing and columnar disjunction formation.

In the last centuries the landscape of gleysols has been taken over by a new meandering river event, eroding it and forming new bars, in a similar lateral process to the previous one, including the development of iron amorphous oxyhydroxide gel rusting, staining red the point bars, giving them rare beauty.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the sedimentological and mineralogical data from the northern region of Bananal Island provides a comprehensive picture of the landscape’s evolution from Holocene to the present. The dynamic interaction of meandering rivers, floodplain development, and sediment deposition has shaped the region’s complex fluvial-lacustrine system. The recurring cycles of erosion, sedimentation, and ferruginization highlight the significant influence of seasonal river dynamics, with ferruginization contributing to the formation of visually striking iron-stained sands. These processes, along with weathering patterns, have been instrumental in forming the region’s distinct sedimentary features. The interaction between vegetation, soil composition, and the mineral-rich sedimentary environment has further influenced the region’s biodiversity, with gallery forests emerging in response to nutrient availability and floodplain conditions. Together, these findings underscore the ongoing transformation of the Bananal Island landscape, shaped by both ancient and modern riverine activities.

6 Acknowledgments

The authors thank CAPES (LASM, grant CAPES/PROEX – 0487 and CNPQ grant 148226/2016-7) for scholarships (MLC, CNPQ grant 305015/2016-8), the GMGA/MUGEO/UFPA team, and the members of the laboratories of Chemical Analysis, X-ray Diffraction and Sedimentology of UFPA for collaboration in laboratory analyses.

7 Author Contributions

LASM conducted the analytical processes, organized and prepared the figures. MLC, MENS and HB designed the project, supervised the research and contributed to interpretation and discussion of the results. All authors participated in fieldwork and sampling and reviewed the manuscript.

8. REFERENCES

AQUINO S, STEVAUX JC & LATRUBESSE EM. 2005. Regime hidrológico e aspectos do comportamento morfohidráulico do rio Araguaia. Rev Bras Geomorfol 2: 29-41.

AQUINO S, LATRUBESSE E & SOUZA FILHO E. 2009. Caracterização hidrológica e geomorfológica dos afluentes da bacia do Rio Araguaia, Brasil. Rev Bras Geomorfol 10 (1): 43-54.

ARAÚJO JB & CARNEIRO RG. 1977. Planície do Araguaia, reconhecimento geológico-geofísico. Petrobrás/RENOR, Belém, Relatório Técnico. 11 p.

BORMA LS, ROCHA HR, CABRAL OM, VON RANDOW C, COLLICCHIO E, KURZATKOWSKI D, BRUGGER PJ, FREITAS H, TANNUS R, OLIVEIRA L, RENNO CD & ARTAXO P. 2009. Atmosphere and hydrological controls of the evapotranspiration over a floodplain forest in the Bananal Island region, Amazonia. J Geophys Res 114: G01003.

BRASIL. 1981. Plano de Manejo: Parque Nacional do Araguaia. Instituto Brasileiro de Desenvolvimento Florestal – IBDF, Fundação Brasileira para a Conservação da Natureza. Brasília, 103 p.

COE MT, LATRUBESSE EM, FERREIRA ME & AMSLER ML. 2011. The effects of deforestation and climate variability on the streamflow of the Araguaia River, Brazil. Biogechemistry 105: 119-131.

DIAS RR, PEREIRA EQ & SANTOS L.F. 2008. Atlas do Tocantins: subsídios ao planejamento da gestão territorial. 5ª ed. Secretaria do Planejamento do Estado do Tocantins, Palmas, Tocantins. 62 p.

EMBRAPA. Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Solos. 1997. Manual de métodos de análise de solo / Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Solos. – 2. ed. rev. atual. – Rio de Janeiro, 212 p.

FOLK RL & WARD WC. 1957. Brazos river bar: A study in the significance of grain size parameters. J Sediment Petrol 27: 3-27.

IRION G, NUNES GM, NUNES-DA-CUNHA C, ARRUDA EC, SANTOS-TAMBELINI M, DIAS AP, MORAIS JO & JUNK WJ. 2016. Araguaia River Floodplain: Size, Age, and Mineral Composition of a Large Tropical Savanna Wetland. Wetlands 36: 94-956.

KUMAR S & SINGH T. 1982. Sandstone dykes in Siwalik Sandstone – Sedimentology and basin analysis – Subansiri District (NEFA), Eastern Himalaya. Sediment Geol 33: 217-236.

LATRUBESSE EM, STEVAUX JC & PRADO R. 1999. The Araguaia-Tocantins Fluvial Basin. Bol Goiano Geogr 19(1): 120-127.

LATRUBESSE ME & STEVAUX JC. 2002. Geomorphology and environmental aspects of the Araguaia fluvial basin, Brazil. Z Geomorphol N.F. Berlin, Suppl.-Bd. 129: 109-127.

LATRUBESSE EM, AMSLER ML, MORAIS RP & AQUINO S. 2009. The geomorphologic response of a large pristine alluvial river to tremendous deforestation in the South American tropics: the case of the Araguaia River. Geomorphology 113: 239-252.

MELACK JM & HESS LL. 2010. Remote sensing of the distribution and extent of wetlands in the Amazon basin. In: JUNK W.J, Piedade MTF, WITTMANN F, SCHÖNGART J, PAROLIN P (eds.) Central Amazonian floodplain forests: ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management: 43-59. Springer, Berlin, DE.

MENDES LAS, PIRES EF, MENESES MENS & BEHLING H. 2015. Vegetational changes during the last millennium inferred from a palynological record from the Bananal Island, Tocantins, Brazil. Acta Amaz 45 (2): 215-230.

MENDES LAS, MENESES MENS, COSTA ML, BEHLING H & PIRES-OLIVEIRA EF 2024. Late Holocene vegetation history and environmental changes from a savanna – forest ecotone zone in the Bananal island, Brazil. Interface 27 (27): 108-123.

MITCHELL ME, LISHAWA SC, GEDDES P, LARKIN DJ, TREERING D & TUCHMAN NC. 2011. Time-dependent impacts of cattail invasion in a great lakes coastal wetland complex. Wetlands 31(6): 1143-1149.

MORAIS RP, AQUINO S & LATRUBESSE E. 2008. Controles Hidrogeomofológicos nas Unidades Vegetacionais da Planície Aluvial do Rio Araguaia, Brasil. Acta Scientiarum. Biol Sci 30: 411- 421.

SIIVOLA J &SCHMID R. 2007. A systematic nomenclature for metamorphic rocks: 12. List of mineral abbreviations. Recommendations by the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks. Recommendations, web version of 01.02.2007.

SUGUIO K. 2003. Geologia Sedimentar. São Paulo: Edgard Blücher, 400 p.

TAYLOR SR & McLENANN SM. 1985. The continental crust its composition and evolution. Oxford, Blackwell Scientific Publications, 312 p.

VALENTE CR. 2007. Controles físicos na evolução das unidades geoambientais da Bacia do Rio Araguaia, Brasil Central. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal de Goiás, 163 p.

VALENTE C & LATRUBESSE E. 2012. Fluvial archive of peculiar avulsive fluvial patterns in the largest Quaternary intracratonic basin of tropical South America: The Bananal Basin, Central Brazil. Paleogeogr Paleoclimatol Paleoecol 356-357: 62-74.

VALENTE CR, LATRUBESSE EM & FERREIRA LG. 2013. Relationships among vegetation, geomorphology and hydrology in the Bananal Island tropical wetlands, Araguaia River basin, Central Brazil. J South Am Earth Sci 46: 150-160.