04 – A CONTEXTUALIZED ARCHAEOLOGICAL PENDANT TO NEPHRITIC JADE IN THE AMAZON: A POSSIBLE LINK TO CARIBBEAN PEOPLE

Ano 11 (2024) – Número 4 – Fulgurites and Sea Glass Artigos

10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v112024i4a4RKP

Marcondes Lima da Costa1*

Renato Kipnis2

Glayce Jholy Valente1

Dirse Clara Kern3

Rômulo Simões Angélica1

1Geosciences Institute, Federal University of Pará, CP 66075-110, Belém-PA, Brazil, marcondeslc@gmail.com, glaycej@yahoo.com.br, rsangelica@gmail.com

2Scientia Consultoria, São Paulo-SP, rkipnis@scientiaconsultoria.com.br

3 Retired from the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, dirse.kern@icloud.com

*Corresponding Author

Submitted to five revision processes during 2019 and 2020/2021 to distinct journal and accepted in 28.09.2024 by BOMGEAM.

ABSTRACT

“Green stone” ornaments from archaeological sites, also known as Muiraquitã, typically a frog-shaped pendant, found throughout Amazonia and the Caribbean, have been known since the 19th century; and were believed to have been carved in jade, an Amazonia exotic raw material supposed to have come from East Asia. The knowledge of the provenience and production of these artifacts is crucial for testing and improving explanatory models on the movement of people and artifacts, as well as on the complexity and entanglement of social networks’ interactions. It was only in the 2000s that Lima da Costa and colleagues were able to show that muiraquitã artifacts were composed by different minerals and the ones closest to jade were tremolite and/or tremolite-actinolite, that are found in the Amazon region. Despite advances in physical/chemistry characterizations of the “Green stone” ornaments, the vast majority have been on artifacts without any archaeological context. We present here the analysis of a pendant excavated from Monte Dourado 1 archaeological site, located in northwest of Pará state, northern Amazonia, near the border with French Guiana and Suriname. The pendant, found within a funerary context, associated with Koriabo ceramics and anthropogenic dark earth, is constituted by nephritic jade or tremolite-type jade; raw material that do occur in the Amazon region. The lack of other lithic artifacts usually associated with the chaîne opératoire for the manufacture of pedants might be an indication that these ornaments were being produced potentially in the Caribbean region. The detailed physical/chemistry characterization of archaeologically contextualized “Green stone” ornaments is crucial for creating a benchmark for these types of artifacts in order to better understand and improve our knowledge about the historical paths taken by pre-colonial societies in the Amazon e Caribbean regions.

Keywords: “muiraquitã”; Monte Dourado; Koriabo; tremolite;

INTRODUCTION

Archaeological research carried out within the environmental licensing process for the Santo Antônio do Jari hydroelectric dam, located on the Santo Antônio waterfall along the Jari river, on the border between the states of Pará and Amapá, in the northern Brazilian Amazon, revealed a semi-translucent green pendant, with contours reminiscent of a preform, and mineral constitution of most so called muiraquitãs, a frog-shaped pendant. Muiraquitãs were believed to be associated with the legendary female Amazon warriors encountered by the Orellana and Carvajal expedition. Objects such as these are very rare, and its finding in an archaeological context presents itself as an object of great importance to advance studies of prehistoric human occupation in the Amazon basin, of tis cultural and technological aspects, and of the discussion about the origin of raw material, especially, because the present specimen was found in situ.

Artifacts like this, here considered as a pre-muiraquitã, were believed to be carved in jade; thus, manufacture from a very rare material, which associated with the archaeological context, have become very valuable (Silva et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2002 a,b; Meirelles & Costa, 2012; Navarro et al., 2017). Muiraquitãs (the general term for frog-shaped pendant found in the Brazilian Lower Amazon) are found in museum collections in Brazil, in Europe and in the Caribbean, as well as with private collectors. They are rarely found in archaeological context, and are thus involved in many stories and legends. In the Caribbean region, similar archaeological artifacts are also known, although not known as muiraquitã, and carved from various geological materials, including jade (Boomert, 1987). Similarly, in the French West Indies Islands, among five dozen beads and pendants, one feature frog-shaped artifacts that may be related to muiraquitã and is made of sudoite (Queffelec et al., 2018), Mg2(Al, Fe3+)3Si3AlO10(OH)8, therefore, a Mg-Al chlorite. Queffelec et al (2018) also mentioned a probable pendant made of nephrite (actinolite). Recently Falci et al (2020) presented two frog-shaped artifacts found in Grenada, eastern Caribbean, which may be related to muiraquitãs, one made in nephrite (actinolite) and the another in “low temperature alteration products”. The scientific interest of these objects began early in the 19th century and some studies concluded that there was no known jade in the Brazilian territory; therefore, the raw material or the objects themselves would have come from East Asia, the region then known as the sole holder of jade, which would reinforce the idea of human colonization of the Americas by migrations from Asia (Rodrigues, 1899).

Some studies have tried to show that the muiraquitãs were manufactured in the region where they were found, for example, around the city of Santarém (Barata, 1954), but these studies don’t discuss the origin of the raw material, which continues to be considered as exotic. In 1906 Ihering attempted to demonstrate that jade occurred in the Brazilian territory, and points to the occurrence of similar material around Amargosa in Bahia. Moraes (1932) also demonstrated the occurrence of jade in Brazil.

It was only in the 2000s that Lima da Costa and colleagues from the Geosciences Institute of the Federal University of Pará, challenged by the inconclusive discussion about the occurrence of jade in Brazil and this being the material considered as raw material of muiraquitãs, decided to investigate whether jade was the main mineralogical constituent of these beautiful and rare artifacts. Soon a great barrier arose, access to manipulation of these artifacts. Resistance was strong, but it was facilitated by the accessibility to the muiraquitã collection of the Museum of Archeology and Ethnography at the University of São Paulo. Equipped with compact instruments, it was possible to collect physical samples and microsamples from the existing orifices. The first mineralogical analysis by XRD and SEM/EDS were performed on these microsamples (Silva et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2002 a, b; Meirelles e Costa, 2012).

The investigated muiraquitã artifacts were composed by different minerals and the ones closest to jade were tremolite and/or tremolite-actinolite (Silva et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2002 a, b), that is, of nephritic jade, as already suspected by Barata (1954). It was then possible to expand the number of samples investigated, which led to the conclusion that most were carved in both tremolite and/or tremolite-actinolite, in addition to amazonite, quartz, talc, pyrophyllite, etc., demystifying jadeite-type jade (Silva et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2002 a,b; Meirelles & Costa, 2012; Navarro et al., 2017). Recently, five specimens made of jadeite-type jade, without any contextualization, were found in the collection of the Pará State Museum of Religious Art (Meirelles & Costa, 2012). Their authenticity, however, has not been fully confirmed. Yet, the muiraquitãs have not lost their majesty. Two years ago, Professor Alexandre Navarro, excavated an archaeological site in Baixada Maranhense (Maranhão Lowland, northeast Brazil) and found a beautiful muiraquitã specimen. Certainly, one of the first muiraquitã recovered within an archaeological context. Mineralogical and chemical analyzes have again proven to be tremolite (Navarro et al., 2017). Despite the fact that the Jari specimen, probably a muiraquitã preform remodeled into a pendant (complete, finished ornament, completed perforation; after definition of ornament-making technical stages from Falci, 2015; Falci et al, 2020), precedes the Baixada Maranhense finding (Caldarelli & Kipnis, 2011), only recently it was feasible its analysis. The study shows that it was carved from material common to that of muiraquitãs in general, green stone, and corroborates the idea that these objects were used by Amazonian people, at least in part, as it was found in an archaeological context. Unfortunately, however, it does not allow to conclude that they were produced by these same peoples, and that they were not object of interregional exchange. The byproducts of the chaîne opératoire associated with the manufacture of muiraquitãs (Falci, 2015) have yet to be found in the Amazon region, let alone in Brazil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

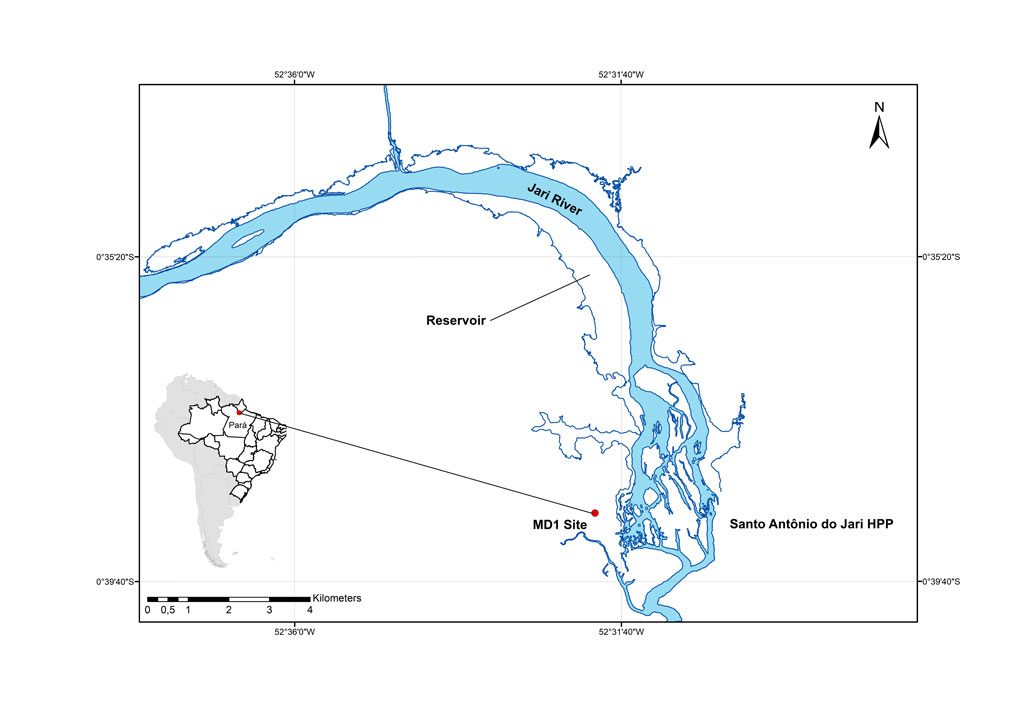

Field activity – The pendant, potentially a muiraquitã preform, was found during archaeological excavation carried out in the area of the then future dam of the Santo Antonio do Jari hydroelectric power plant, in the middle course of the Jari river, in the northwest of Pará state, northern Amazonia, near the border with French Guiana and Suriname and close to the domain of the Tumucumaque mountain ridge.

The research at Santo Antônio do Jari hydroelectric power plant encompassed the excavation of Monte Dourado 1 archaeological site (MD 1). The site is located on the top of a hillside at the southeast end of a plateau 300m above sea level, close to the Santo Antônio do Jari falls (Figure 1). The archaeological site lays on top of a dystrophic yellow red latosol, and its A horizon is an organic rich black soil rich on ceramic fragments and some lithic materials, which corresponds to what it is known as Terra Preta or Anthropogenic Dark Earth, an anthropogenic soil associated with past human settlements found through Amazonia (Lehmann et al., 2003; Woods et al., 2008; Meirelles and Costa, 2012; Glaser and Woods, 2013).

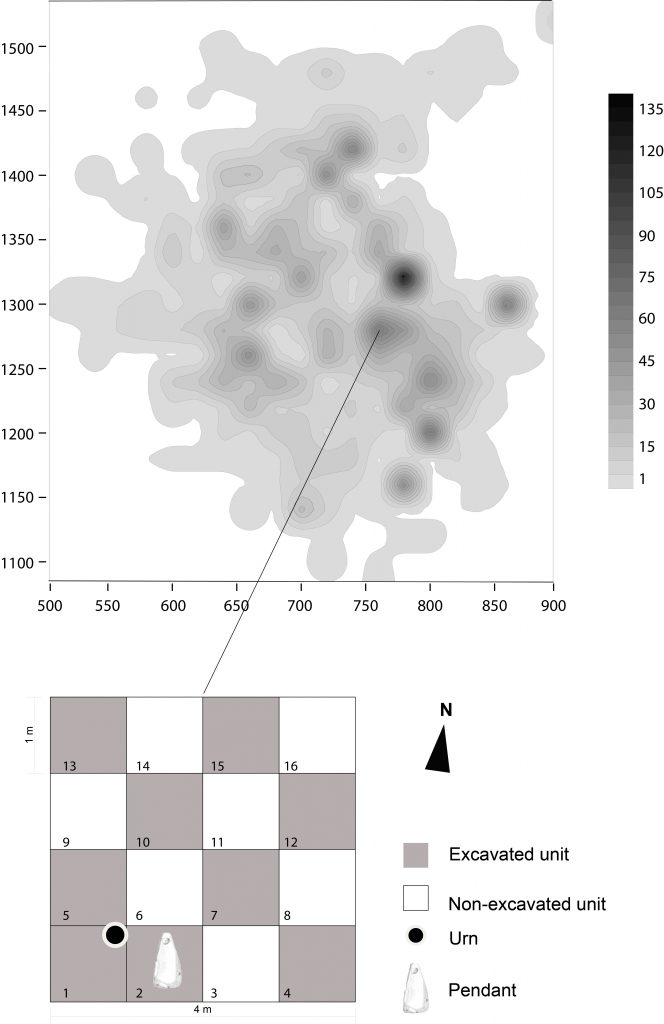

Monte Dourado 1 is a habitational open-air site, with a total area do 235.200m², characterized by the high density of archaeological material, mainly ceramics and lithics (Figure 2), the presence of a 40cm thick archaeological strata, mainly black (7.5YR 2.5/1) and dark-brown (7.5YR 3/3) sandy-clay soils, with relative high contents of nutrients such as Ca, Mg, K, and P, characteristics of a high fertility soil like the archaeological dark earths. Preliminary morphological analysis of the ceramic collection indicates an association with Koriabo pottery (Cabral, 2011).

Extensive excavations carried out in the site uncovered two areas associated with funerary context, presenting urns with human remains inside and outside the vessels, also, associated with this context were ceramic and lithic artifacts (Figure 2).

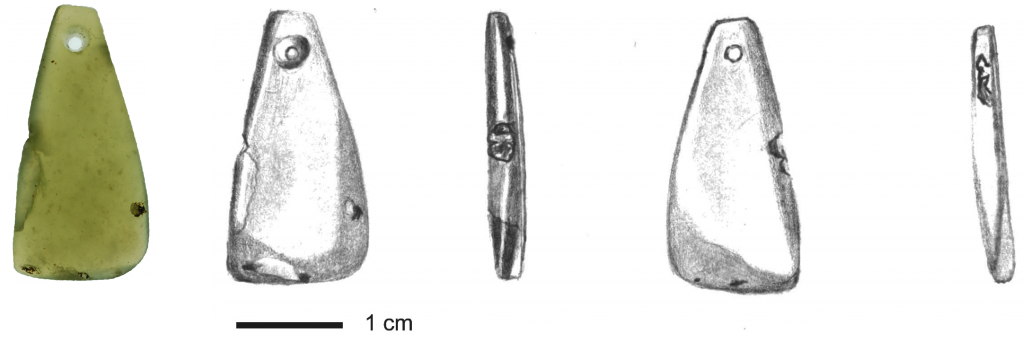

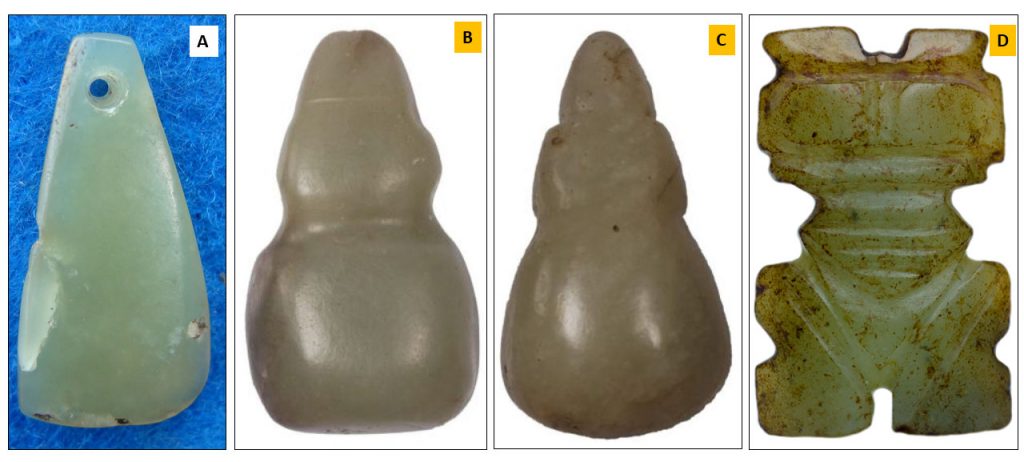

In area SA3 of the MD 1 site, a single lithic artifact made on “green stone” was recovered during excavation in spatial association with a funerary urn (Figure 2). The artifact is a small triangular pendant (25.21 mm tall, 12.46 mm wide, and 2.97 thick as maximal measurements), presenting a small perforation in one of the vertices, and completely polished (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Location of the Santo Antônio do Jari hydroelectric power plant and MD1 site, where the pendant has been found. (Source: Scientia Consultoria).

Figure 2. Monte Dourado 1 (MD 1) archaeological site, cultural material distribution and density, and funerary area SA3. (Source: Scientia Consultoria).

Figure 3 – The place where the pendant has been found beside a funerary urn (white arrow) in the dark earth soil, anthropogenic strata visible on the profile showing the A horizon upward. (Source: Scientia Consultoria).

The archaeological rescue activities were carried out by Scientia Consultoria, under the direction of Drs. Solange Caldarelli and Renato Kipnis and the participation Dr. Dirse Clara Kern of the Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi. The pendant was found on 01.09.2011 in the 0-10 cm excavation level. It is deposited in the IEPA collection in Macapá city, state of Amapá, Brazil.

Cleaning – For cleaning it still in the field, it was used only a simple and soft brush and water, then placed in a small plastic bag, labeled and filed under code MD-1 SA3. It was later delivered to prof. Dr. Marcondes Lima da Costa from Geosciences Institute of Federal University of Pará, in Belém do Pará, on November 29, 2011 by Dr. Dirse Clara Kern. On this occasion Professor Marcondes performed the first laboratory analysis and found that it was tremolite.

Mesoscopic Analysis – Measurements of the pendant’s main dimensions were made with a digital caliper. A drawing depicting the pendant’s triangle shaped form, presenting a hole in one of its extremities, was made and the total density was measured with the aid of the Kraus-Jholy balance. Then images were obtained with digital camera direct on the object and with the aid of dino-lite digital microscope and a stereomicroscope.

Mineralogical analysis – Mineralogical identifications was performed by X-ray diffraction directly on the object, because fortunately due to its size, thickness and morphology, it was properly installed in the equipment sample holder. The Bruker X-ray diffractometer, model D2 Phaser, from the PPGG_IG / UFPA LAMIGA laboratory was used and the interpretation of the spectrum was performed with X´pert High Score Plus software from PANalytical from the PPGG_IG-UFPA Mineral Characterization Laboratory. The equipment was equipped with copper anode (λCu Kα = 1.54184 Ǻ) under operating conditions of 30 kV voltage and 10 mA current, 0.02 pitch and 0.2s pitch time with Lynxeye detector.

Chemical analysis – A direct quantitative analysis was performed directly over the pendant artifact with the aid of X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry, using a sequential WDS spectrometer, model Axios Minerals of the PANalytical Company, with ceramic X-ray tube, rhodium anode (Rh) and maximum 2.4 KW power level, carried out at Mineral Characterization Laboratory of Geosciences Institute of Federal University of Pará. In parallel four other analyzes were performed with the aid of portable X-ray fluorescence from Bruker S 1 Turbo from LAMIGA laboratories of the same Institution directly on the pendant, without any special treatment. For these reasons the results should be viewed as semi-quantitative. Another semi-quantitative microanalysis directly on the pendant were performed by scanning electron microscopy with dispersive energy system (SEM/EDS). For this case, the HITACHI model TM 3000 equipment and the EDS 3000 system with Swift ED software coupled with the SEM were used. The sample was not metallized and the analysis were performed under low vacuum.

RESULTS

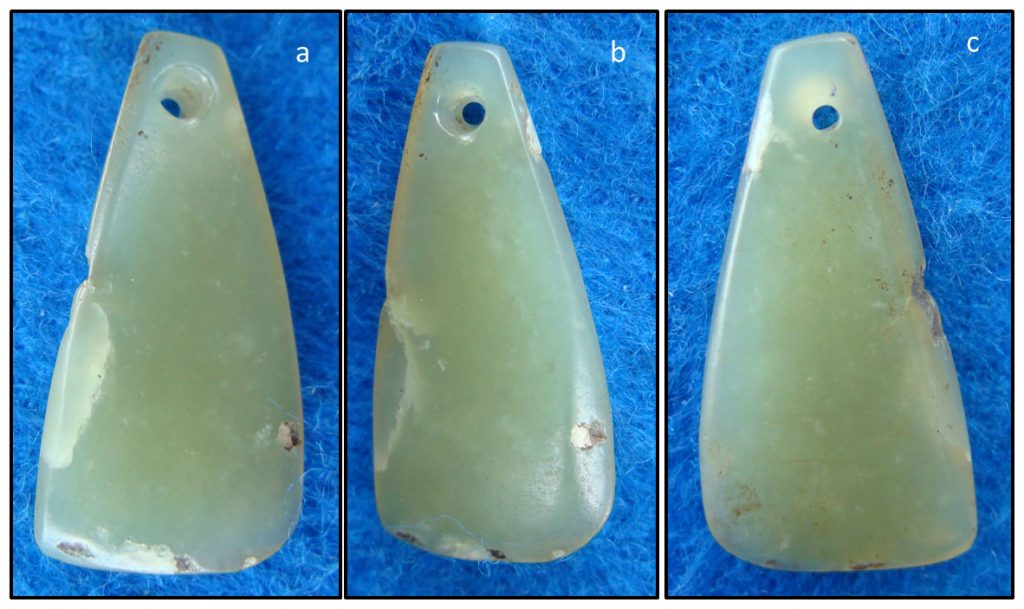

Physical and Morphological Characteristics – The pendant is a tabular piece with triangular shape, measuring 25.21 mm in length, with a maximum width of 1.35 cm and a minimum of 0.35 cm and a thickness ranging from <1 to 2.97 mm (Figure 4). It weighs 1.65g and the measured density is 2.98. Its color ranges from light green to almost white. The tapered perforation, ranging in diameter between 0.55 and 2.40 mm, is located at the narrow end (Figure 4 and 5). The tapered perforation is scaled in four levels (Figure 6 a), indicated by four sub-steps (Figure 6 b), suggesting the use of cylindrical drills with three different diameters. The surface of the entire artifact’s body is smooth, sub-planar, with partially rounded edges. The piece has no carvings, and apparently the craftsman tried to make the best of the original stone. Several fissures are present (Figure 5), which probably imposed some difficulties during manufacturing the piece, but didn´t hindered its completion. Also in the piece stand out micro-fissures were partially filled with local anthropogenic dark soil materials from the archaeological site, known in laboratory jargon as dirt (Figures 7 a and b) represented by kaolinite. Abundant rectilinear scratches running into three major directions reflect abrasive and polishing technics (Figure 7 a). Although the overall shape suggests a possible intention for the production of muiraquitã, which has a general triangular outline, the intention was not achieved, certainly due to the small thickness, the presence of micro-fissures and inclusions of soft minerals, such as clay, which it is confirmed by insertion of a conical frontal perforation (Figures 4 to 6), unlike the muiraquitãs which generally present lateral perforation.

Figure 4. Main morphological aspects of the pale green stone pendant (from left to right): a) frontal photo where conical aspect of perforation and triangular shape of the piece are clearly visible, b) hand drawing of frontal side depicting a small crack along the bulging edge as well as the reduce of body mass at the wider end of the piece; c) left lateral view showing small broken area edge; d) back of the piece also the small crack along the bulging edge as well as the reduce of body mass at the wider end of the piece, and the narrow opening of the perforation; e) right lateral view.

Figure 5 – Detailed images of the pendant: a and b) frontal view showing the conic perforation, cracks and fissures with soil materials (small dark spots); c) back view also showing cracks and fissures with soil materials (small dark spots), and the opposite end of the perforation.

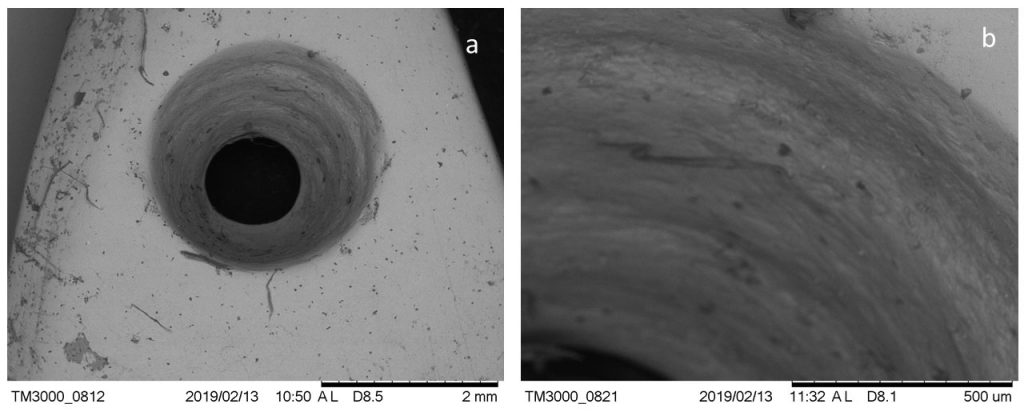

Figure 6 – SEM micrographs: a) conic small perforation; b) detail on the wall surface of the perforation showing four distinct levels formed by using three distinct cylindric artifacts, probably stone drills.

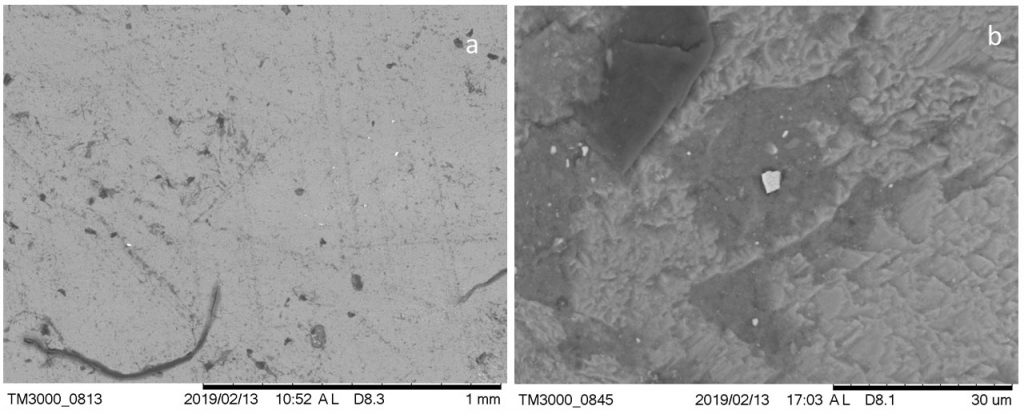

Figure 7 – SEM micrographs on the surface of the artifact: a) showing the stretch marks on the pendant polished surface; b) showing the typical acicular habits for tremolite (gray area) and the presence of clay mineral (dark gray area), mostly kaolinite, dirtiness, may Dark Earth soil (very dark area) and some opaque iron-chromium oxides (very small light gray area), possibly chromite.

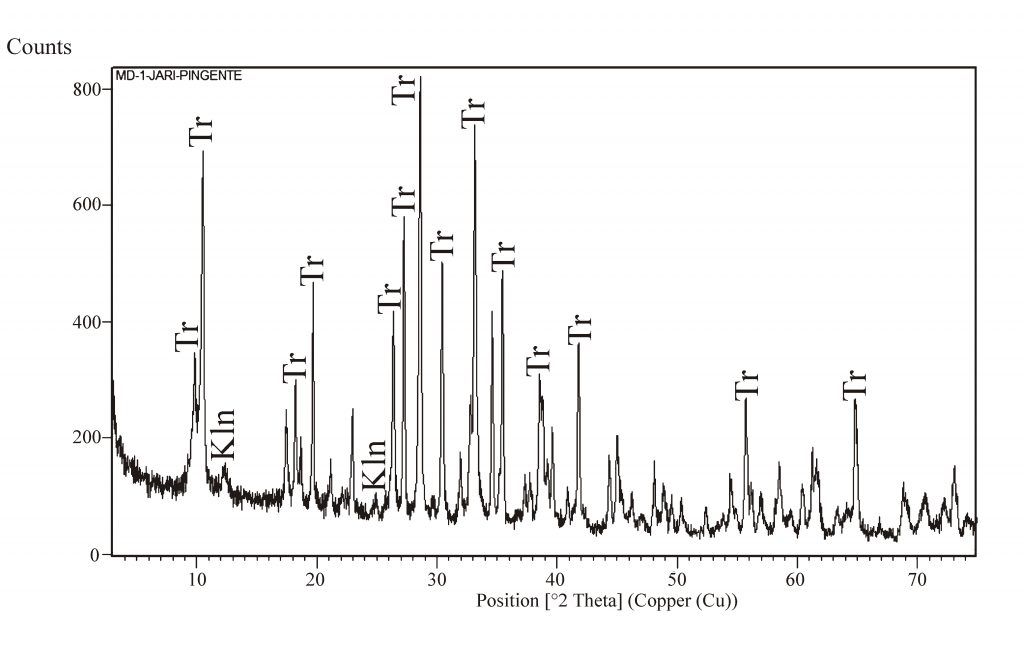

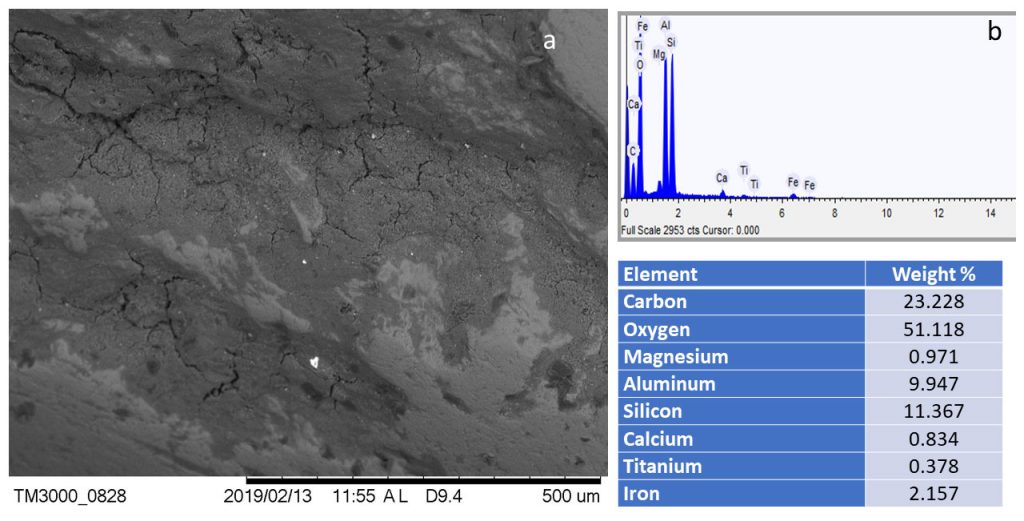

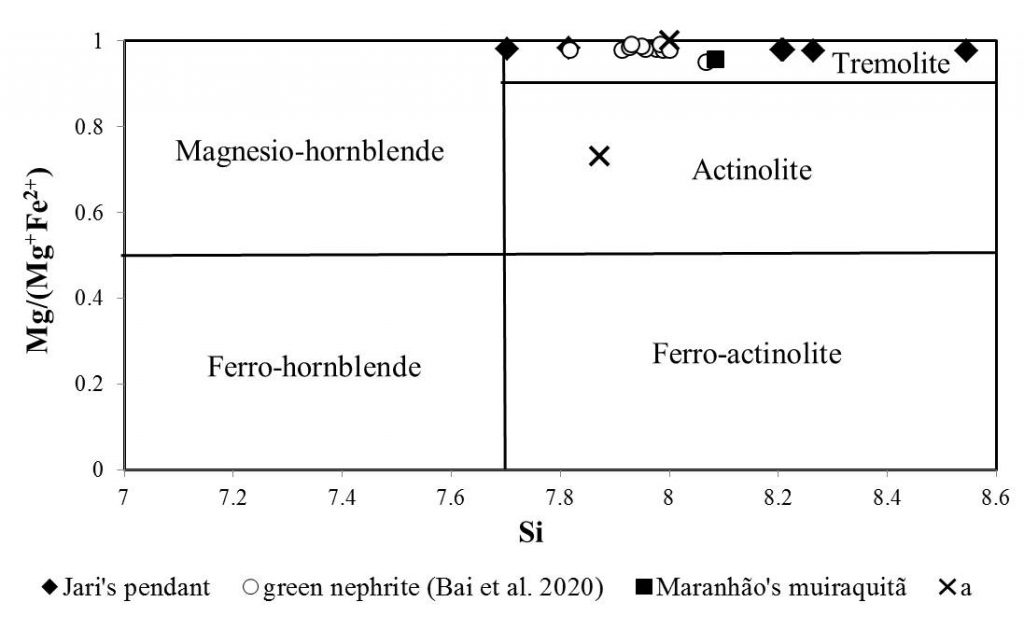

Mineralogical and chemical constitution – The body of the pendant is constituted by tremolite (Figure 8), i.e., nephrite-type jade, the mineral constitution of many pendants, especially Amazonian muiraquitãs (Silva et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2002 a, b; Meirelles and Costa, 2012). This constitution was confirmed by chemical analysis, which show low Fe2O3 content (<0.80%), thus eliminating the possibility of being tremolite-actinolite, which is relatively much richer in Fe2O3 (Tables 1 and 2). In fact, the color of the piece is at most a very pale green or even white, incompatible with tremolite-actinolite, which is usually a deep green. Kaolinite was locally identified according to SEM/EDS (chemical images and microanalysis) results and XRD analysis (Figure 8). It partially occupies the microcavities and inter-crystalline spaces of tremolite mass. The presence of kaolinite, in addition to the XRD spectra (Figure 8), is confirmed by Al2O3 and SiO2 levels, which are beyond the congruent for stoichiometric tremolite (Tables 1 and 2), and also by SEM / EDX analysis (Figure 9), what masked the pfu calculations (Table 1). The tremolite of Jari’s pendant resembles that of green nephrite from Dahua, Guangxi, Southern China (Bai et al., 2020), of gemological use, in all physical and chemical aspects. The only divergence is in the slightly higher contents of SiO2 and Al2O3, which, as already mentioned, reflects the presence of kaolinite. The apfu values are equivalent; therefore, falls within the range of tremolite (Figure 10). The acicular appearance shown in the SEM image and the SEM/EDS microchemical results are also compatible with tremolite and the gray fine masse with kaolinite from the soil materials (Figure 7 and Table 1).

Figure 8 – XRD spectrum analysis carried out directly over the pendant (MD 1 SA3) surface showing the domain of tremolite (Tr), being kaolinite (Kln) restrict.

Table 1 – Chemical composition after portable XRF (EDS) at four-point analyses (1, 2, 3 and 4) and their average and XRF (WDS) compared to tremolite of Maranhão muiraquitã (recalculated), theoretic tremolite and actinolite, and respective apfu (atoms per formula unit) values. aNavarro et al. (2017); bWebmineral.com; b Obtained by difference; c Considered to be 2,20 by correlation to theoretic tremolite and actinolite.

| Chemical oxides | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Average (1 to 4) | XRF-WDS | Maranhão´s muiraquitãa | Tremoliteb | Actinoliteb |

| MgOb | 16.21 | 24.19 | 19.44 | 20.05 | 19.97 | 22.82 | 25.73 | 24.81 | 16.11 |

| Al2O3 | 2.40 | 1.95 | 2.22 | 2.02 | 2.15 | 3.13 | 0.93 | – | 2.63 |

| SiO2 | 64.10 | 57.60 | 61.60 | 61.00 | 61.08 | 56.56 | 60.32 | 59.17 | 54.86 |

| Cl | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | – | – | – | – |

| K2O | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | – | – | – | – |

| CaO | 14.20 | 13.20 | 13.60 | 13.80 | 13.70 | 14.50 | 7.82 | 13.81 | 12.03 |

| MnO | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | – | – | 0.17 | |

| Fe2O3 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0,77 | 2.07 | – | 10.61 |

| Others | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.90 (Na2O) | – | 1.48 |

| LOIc | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.22 | 2.22 | 2.22 | 2.11 |

| 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99,99 | 100.01 | 100.00 | |

| apfu | |||||||||

| Si | 8.546 | 7.816 | 8.265 | 8.206 | 8.210 | 7.702 | 8.084 | 8.000 | 7.872 |

| Ti | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Al | 0.377 | 0.312 | 0.351 | 0.320 | 0.341 | 0.502 | 0.147 | 0.000 | 0.445 |

| Fe+3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Fe+2 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.090 | 0.086 | 0.082 | 0.088 | 0.232 | 0.000 | 1.273 |

| Mn | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.021 |

| Mg | 3.222 | 4.893 | 3.888 | 4.021 | 4.002 | 4.633 | 5.140 | 5.000 | 3.446 |

| Ca | 2.029 | 1.919 | 1.955 | 1.989 | 1.973 | 2.116 | 1.123 | 2.000 | 1.849 |

| Na | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.234 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| K | 0.017 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| H | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 |

Table 2 – Chemical composition after SEM/EDS (1 and 2-point analyses). DL: Detection Limit. aWebmineral.com. b Theoretical value.

| Chemical oxides | 1 | 2 | Tremolitea | Actinolitea |

| MgO | 23.40 | 23.15 | 24.81 | 16.11 |

| SiO2 | 61.08 | 56.75 | 59.17 | 54.86 |

| Al2O3 | 1.56 | 1.48 | – | 2.63 |

| CaO | 12.51 | 10.45 | 13.81 | 12.03 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.92 | <DL | – | 10,61 |

| H2Ob | – | – | 2.22 | 2.22 |

Figure 9 – a) SEM image of the pendant surface. The dark gray area represents dark earth soil stains and the white points Fe, Ti oxides; b) EDX/SEM chemical analysis (spectrum and table) for dark gray area illustrating the domain of Al, Si and O, that is, kaolinite, and possible organic carbon (soil material and dirtiness on the surface of the tremolite-bearing pendant, which is indicated by Ca, Mg, besides Si, O and Fe oxyhydroxides and anatase represented by Ti and O partially).

Figure 10 – Plotting of apfu for Jari pendant (this study), Maranhão´s muiraquitã (after chemical analyzes from Navarro et al., 2017) and the gemological nephrite from Dahua, Guangxi, Southern China (Bai et al., 2020).

DISCUSSIONS

Based on the triangular morphology and the size of the pendant, as well as the slightly greenish color and the generally high hardness, common characteristics usually present in Amazonian lithic adornments, it is possible to suggest that the craftsman had initially the intention of carving a muiraquitã, a frog-shaped pendant displaying a general outline, similar to two specimens from Amazonia, but with no archaeological context (Figure 10); however it diverges from the contextualized Maranhão’s muiraquitã; but all of them were carved in tremolite. The frog-shaped pendants are also common in the Carribean region, especially in Gare Maritime (Cody, 1993), carved in different stones or minerals, mostly green stones, even tremolite, as described by Queffelec et al. (2018). The two nephrite-three-dimensional frog-shaped pendants from Pearls were compared to as muiraquitãs and they belong to Saladoid contexts (Falci et al, 2020). These authors also mention the flat “segmented frog pendants” with a perforation across the neck and made of varied raw materials (serpentinite, jasper, nephrite and calcite) that belong to Huecoid peoples and do not display carving, as the Jari pendant. It is conceivable that during the attempt to model the batrachian form of the muiraquitã, the carver, confronted with the presence of fractures, fissures, in addition to microcavities with clay mineral, kaolinite, and low hardness, which could break the whole stone and impede the drilling of lateral perforations; decided to manufacture the pendant by shaping the round edges and making the single conical perforation. It may not be incidental that the perforation was performed at the thickest part of the piece, where potentially would be the batrachian’s head. The final product was a beautiful green stone pendant, reminding a muiraquitã. The nature of the stone constituted of material appreciated at the time, which today corresponds to tremolite, certainly made the craftsman to seek a piece of greater prestige. It was faced with the best natural material for making these adornments, known to this day as nephrite-type jade. On the other hand, the pale hue of green slightly diminished the appraisal of many pendants when compared to pendants carved on beautiful green tremolite-actinolite, although many other pendants were manufactured on less valued material, such as amazonite, quartz, talc, etc. (Silva et al. 1998; Costa et al. 2002 a, b; Meirelles & Costa 2012). The non-destructive mineralogical and chemical analyzes performed in this piece and in the others already published (Silva et al. 1998; Costa et al. 2002 a, b; Meirelles & Costa 2012) allow us to construct more robust explanations. Unlike many other Amazonian archaeological pendants, the one investigated in this work was one of the first found in archaeological context, a few inches deep, in a site with archaeological dark earth soils, a strong feature of archaeological sites of the Amazonian ceramists (Lehmann et al. 2003; Woods et al. 2008; Glaser & Woods, 2013), and next to it a funeral urn, which suggests that this pendant was deposited next to the human body, which had it as a personal adornment of great appreciation and symbolism or as deference, a real jewel, following the line of deduction observed in Queffelec et al (2018) and Falci et al (2020).

Figure 11 – A) The contextualized tremolite pendant MD 1 SA3 of this study, 2.521 cm length; B) and C) two non-contextualized Amazon muiraquitãs carved in tremolite-actinolite, 5.5 cm and 3.0 cm length, respectively (Meirelles et al., 2012); D) the contextualized tremolite Maranhão´s muiraquitã, 2.92 cm in length (Navarro et al., 2017).

Based on the discussion above, the native peoples inhabiting northeast Amazonia, producers of archaeological dark earth and elaborate ceramic objects, also wore adornments manufactured from common to semiprecious minerals, as already noted by Rodrigues (1899) and Barata (1954) and disposed them in burial context, as personal object of value, which should be taken by the owner in post-mortis. Regarding the site under consideration, Monte Dourado 1, the analysis of ceramics reports the occupation by the Koriabo people (Cabral, 2011; Caldarelli & Kipnis, 2011). The resemblance of these objects to those more and more often described in the Caribbean region, where the mineral diversity is fantastic, including nephite-type, and perhaps jadeite-type jade, and many others (Boomert, 1987; Queffelec et al., 2018) allows us to suggest that Amazonian people kept an exchange network that supplied adornments like the one described above. While in the Caribbean there has already been strong evidence for the pendant’s manufactured chaîne opératoire associated to the Saladoids’ people around 250 to 400 cal. A.D. (Queffelec et al., 2018), in the Amazon the archaeological record lacks evidence for the local manufacture of theses adornments. Barata (1954) describes a possible occurrence of raw material in archaeological sites near of what is today the city of Santarém, which he interprets as a possible area for the occurrence of lithic pieces associated with the chaîne opératoire for the production of adornments like muiraquitã.

The persistence of Amazonian pendants found in archaeological context or not and carved in tremolite (Figure 10) suggests the appreciation of this raw material in ancient times, which continues on to the present. A good example is represented by the deposit of gemological nephrite from Dahua, Guangxi, Southern China explored today as a gemological raw material (Bai et al., 2020). It is probable that the geological source for this material be local, once tremolite and tremolite-actinolite, as already proposed by Costa and colleagues (Costa et al., 2002 a, b), are not rare minerals, and rocks with these minerals are known in the region, but to date, no occurrences have been identified with the quality observed in these pendants. However, Ihering (1906) already reported the occurrence of these minerals in Amargosa, Bahia state. Moraes (1932) also reinforces the presence of these minerals in the Brazilian territory. In Amargosa, traditional local families have several artifacts in their personal collections, mainly beads, similarly to green stones, tremolite and/or tremolite-actinolite (Silva et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2002 b).

Today, it is known that in the geology of Neoproterozoic to Paleoproterozoic terrain, rocks such as marbles and skarns, rich in or bearers of tremolites and/or solid to compact-fibrous tremolite-actinolite, of gemological characteristics are present. In the Amazon these minerals are usually associated with Proterozoic terrains formed by hydrothermalized and/or metamorphic mafic to ultramafic rocks. Therefore, in principle, potential raw material was available.

On the other hand, archaeological studies show the Koriabo people inhabited a large region, notwithstanding regional differences, extending from the Guyanas to the Xingu River (Chmyz and Sganzerla, 2006; Rostain, 2008, 2013; Cabral, 2011; Fernandes et al., 2018), with probable connections to the Caribbean-speaking peoples (Cabral, 2011; Fernandes et al., 2018). As shown earlier, these peoples dominated the chaîne opératoire for manufacturing pendants and beads in various gemological materials, including greenstones (Queffelec et al., 2018) Therefore, the MD 1 SA3 pendant seems to strengthen the line of thought that suggests close contact between the Koriabo people of the MD1 and Karib communities, many inhabiting apparently isolated islands, or even a mixture of regional and continental connections and origins, thus strengthening the idea of pan-Caribbean network for exchange of raw materials (Boomert, 1987; Queffelec et al., 2018; Falci et al., 2020). Pearls in the eastern Caribbean sites may have been a center for producing pendants, with local or imported material, such as frog-shaped pendants, equivalent to muiraquitãs, some of them made in nephrite, mainly for export (Falci et al., 2020). These authors also suggest that nephrite ornaments may have been acquired through exchange, used as bodily adornment and ultimately deposited with the dead, similarly it must have occurred with the Jari pendant, studied here. It is very likely that muiraquitãs or similar pendants had a strong connection with the Caribbean region, like Pearls. The similarities between the ornaments and the constituent material are very strong.

CONCLUSIONS

The pendant investigated here was probably initially conceived to be shaped as a muiraquitã suggested by the triangular shape and size, and mainly by the geological material, the nephritic jade or tremolite-type jade, much appreciated among the pendants, especially the muiraquitã; but its thickness, the fissures and microcavities certainly became a deterrent for manufacturing a muiraquitã. It is a piece of great historical value, as it was found in an archaeological funerary context a few inches below surface, and related to the Koriabo people, whom had contacts and exchange networks with the Karib-speaking people. Similar artifacts to MD 1 SA3 are known from the Caribbean region, produced in similar or non-similar materials in various shapes and forms, including frog-shaped, and by people whom were, at least partially, contemporaries of the Koriabo societies. It is very likely that muiraquitãs or similar pendants in Amazon had a strong connection with the Caribbean region, like Pearls.

On the other hand, tremolite- and tremolite-actinolite-type jade is not unknown in the geology of Brazil or Amazonia. However, the byproducts of the chaîne opératoire for manufacturing these objects, like flakes and debris from these materials has not yet been conclusively found in the Brazilian territory.

Acknowledgments

To Scientia Consultoria Científica for making the piece available for study and to CNPq for financial support (Bench Rate and Productivity Scholarship 305015/2016-8) and to the LAMIGA laboratories of PPGG / IG_UFPA in supporting the analyzes.

REFERENCES

Bai, F., Du, J., Li, J., Jiang, B. 2020. Mineralogy, geochemistry, and petrogenesis of green nephrite from Dahua, Guangxi, Southern China. Ore Geology Reviews, 118:103362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2020.103362.

Barata, F. O muiraquitã e as contas dos Tapajós. Revista do Museu Paulista, v.8, p. 229-252, 1954.

Boomert, A. 1987. Gifts of the amazons: green stone pendants and beads as items of ceremonial exchange in Amazonia and Caribbean. Antropologica, 67: 33-54.

Cabral, M. P. 2011. Juntando cacos: uma reflexão sobre a classificação da fase Koriabo no Amapá. Amazônica, 3 (1): 88-106.

Caldarelli, S. B. & Kipnis, R. 2011. Projeto de Arqueologia Preventiva nas áreas de intervenção da UHE Santo Antônio do Jari, AP/PA. Relatório parcial: Resgate de campo do Sítio Monte Dourado 1. Scientia Consultoria Científica, São Paulo.

Chmyz, I. & Sganzerla, E.M. 2006. Ocupação Humana na Área do Complexo Jari. Arqueologia, Curitiba. 9: 129-149.

Cody, A., 1993. Distribution of exotic stone artifacts through the Lesser Antilles: their implications for prehistoric interaction and exchange. In: Cummins, A., King, P. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology, pp. 204–226.

Costa, M.L., Silva, A.C.R.L., Angélica, R.S. 2002 a. Muyrakytã ou muiraquitã, um talismã arqueológico em jade procedente da Amazônia: uma revisão histórica e considerações antropogeológicas. Acta Amazonica, 32(3): 467-490. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-43922002323490.

Costa, M.L., Silva, A.C.R.L., Angélica, R.S., Pöllmann, H., Schuckmann, W. 2002 b. Muiraquitã ou muyrakytã, um talismã arqueológico em jade procedente da Amazônia: aspectos físicos, mineralogia, composição química e sua importância etnogeográfica- geológica. Acta Amzonica, 32 (3): 431-448. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-43922002323448.

Falci, G.C.2015. Stringing beads together: a microwear study of bodily ornaments in late pre-Colonial north-central Venezuela and north-western Dominican Republican. Universiteit Leiden Archeologie. Leiden, Netherlands.

Falci, G.C., Knaf, A.C.S., van Gijn, A., Davies, G.R., Hofman, C.L. 2020. Lapidary production in the eastern Caribbean: a typo-technological and microwear study of ornaments from the site of Pearls, Grenada. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2020) 12:53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-01001-4.

Fernandes, G.C.B., Lima, H. P., Ribeiro, A.B. 2018. Cerâmicas Koriabo e problematizações iniciais sobre a Arqueologia na foz do rio Xingu. Habitus Goiânia, 16 (2): 403-424. DOI 10.18224/hab.v16i2.5889.

Glaser, B. and Woods W.I. 2013. Amazonian Dark Earths: Explorations in Space and Time. Springer Science & Business Media. New York.

Ihering, H. von. 1906. Ueber das natuerliche Vorkommen von Neprit in Brasilien. In: Int. Amcrikanisten-Kongress, 14, Stuttgart, 1904, Verlag von W. Kohlhammen, vol.2:507-515.

Lehmann, J.; Kern, D.C.; Glaser, B. and Woods W.I. 2003. Amazonian Dark Earths: Origin, Properties, Management. Springer Science & Business Media. New York.

Meirelles, A.C.R., Costa, M.L., 2012. Mineralogy and chemistry of green stone artifact (muiraquitãs) from the museums of the Brazilian State of Pará. REM: Revista da Escola de Minas, Ouro Preto, 65(1): 59-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0370-44672012000100008.

Moraes, L.J. de, 1932. Sobre o jade no Brasil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 4(2): 63-66.

Navarro, A.G., Costa, M.L., Silva, A.S.N.F., Angelica, R.S., Rodrigues, S.F.S., Gouveia Neto, J.C. 2017. O muiraquitã da estearia da Boca do Rio, Santa Helena, Maranhão: estudo arqueológico, mineralógico e simbólico. Bol. Mus. Pará, Emilio Goeldi, Cienc. Hum., Belém, 12(3): 869-894.

Queffelec, A., Fouéréb, P., Paris, C., Stouvenote, C., Bellot-Gurlet, L.2018. Local production and long-distance procurement of beads and pendants with high mineralogical diversity in an early Saladoid settlement of Guadeloupe (French West Indies). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 21 (2018) 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.07.011

Rodrigues, B., 1899. O muyrakytã e os ídolos simbólicos. 2ª. edição, Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, (1): 210p.

Rostain, S. 2008. The Archaeology of the Guianas: An Overview, in Handbook of South American Archaeology, pp. 279-302. Edited by H. Silverman & W. H. Isbell. New York: Springer.

Rostain, S. 2013. Islands in the Rainforest: Landscape Management in Pre-Columbian Amazônia. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

Silva, A.C.R.L., Costa, M.L. Angélica, R.S. 1998. O muiraquitã (muyrakytã): REM: Revista da Escola de Minas, Ouro Preto, 51(2): 24-29.

Woods, W.I.; Teixeira, W.G.; Lehmann, J.; Steiner, C.R.; WinklerPrins, A.M.G.A; Rebellato, L. 2008. Amazonian Dark Earths: Wim Sombroek’s Vision. Springer Science & Business Media. New York.