03 – SOME SEA GLASS PEBBLES FROM SÃO MIGUEL AZORES, PORTUGAL: PHYSICAL FEATURES, CHEMISTRY AND POTENTIAL RAW MATERIALS

Ano 11 (2024) – Número 4 – Fulgurites and Sea Glass Artigos

10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v112024i4a3MLC

Marcondes Lima da Costa1*

Susana Horta2

Glayce Jholy Souza da Silva Valente3

1Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brazil, marcondeslc@gmail.com

2São Miguel Azores, Açores, Portugal

3PPGPatri, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brazil

*Author for correspondences

Received: July 31, 2024; accepted: August 18, 2024.

ABSTRACT

Three Sea Glass pebbles collected on the shoreline of the island of São Miguel Azores, in Portugal, called white, blue and black, were analyzed by mesoscopic means, and by XRD, XRF (handheld), and SEM-EDS. They are rounded, matte, and translucent, with a hardness of around 6 and low density. They are all amorphous to XRD. All three have the same proportion in Si (SiO2) and Al, while they differ in most of the other chemical components. White and blue are sodium-potassium-barium, and black are sodium-calcium. Blue has Co as its pigment, while black has Fe/Mn oxyhydroxides. It is likely that quartz sand, quartz containing Al and Ti, was added at least in part as plant ash (Na, K, Mg, S, Cl). However, Ba may have had calcined barite as its raw material, which appears sporadically in microaggregates. Therefore, the Azores SG could be classified as possible genuine sea glass.

INTRODUCTION

Sea Glass (SG) is in general a fragment of historical glass utensils, between the 17th and 19th centuries, until the first two decades of the 20th century, transported, worked and deposited by sea waves on continental and island shores and beaches around the world. The most striking deposits are in the northeast United States, northeast England, Mexico, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Italy, Russia (Siberia), Greece, Iceland, Scotland, Japan and Australia. According to Science ABC (2024): “Sea glass is smooth, frosted, beautiful pieces of glass that are found on the beaches beside oceans and seas. They are formed from man-made glass products and are polished and refined by the waves and currents of oceans, as well as a few other natural phenomena.” (https://www.scienceabc.com/nature/what-is-sea-glass-and-where-does-it-come-from.html, accessed on July 22, 2024). In addition, the same author informs that “the term sea glass is used to refer to the small pieces of glass that are typically found on beaches along bays, seas and oceans, but they can also be found on the banks of large rivers. Sea glass is weathered both physically and chemically due to the constant tumbling action of waves over an extended period of time.” SG are distinguished from Beach Glass, although they have physical and chemical similarities between them, the first ones are restricted to salty marine and oceanic waters, while the last to freshwater beaches. But in many cases the two terms are used with practically the same meaning.

Although collectors, jewelers and dealers in SG use expressions such as Naturally occurring sea glass (sometimes colloquially referred to as “genuine sea glass”, natural sea glass. The term natural in geosciences and materials sciences does not find resonance, as is exclusive to allude to materials of natural origin, without intentional human interference. The SG is a discarded fragment of glasses, such as bottles, tableware, pieces of household items elaborated by humans and lost in natural disasters and even shipwrecks, which are tossed on the shore as the result of various human activities, even son as old wastes. SGs are thus human products, cut (fragmented), faceted and frosted by nature, while for example diamonds are produced by nature and cut and polished by humans. These same SG collectors, jewelers and dealers recognize Artificial Sea Glass, formed in a workshop, factory or even a rock tumbler (very rare). People also make artificial sea glass from recycled glass bottles.

“Natural” SG comes in various colors: white, very common, coming from old soda, medicine, or liquor bottles; brown, also common from beer, whiskey, or medicine bottles; green, early to mid-1900s soda bottles, or from wine, fruit jar, and baking powder containers.; blue, medicine bottles, poison bottles, or Bromo-Seltzer bottles; Milk of Magnesia, ink bottles, or fruit jars; red, very rare, boat lights, and decorative household items; yellow, not common; purple; black, older, thick glass bottles of the 18th and 19th centuries; pink; gray, from older window panes or jar glass; sea turquoise, from early 1900s soda bottles, medicine bottles, or art glass (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 – Some examples of the colors and shapes variety of sea glass. Source: https://www.recyclethesea.co.uk/post/the-history-of-sea-glass#:~:text=Whilst%20you%20would%20be%20incredibly,often%20land%20on%20the%20shorelines. Accessed on July 22, 2024.

Although it might be more charming to describe that sea glass is a term for some type of naturally forming material, the fact is that it begins its journey to beauty as nothing more than ordinary glass, mostly old bottles and jars, broken dishware and even glass windshields and taillights from older cars. Due to characteristics, such as rarity, range of colors and diaphaneity, SG are widely used in jewelry as noted by sea glass artist Jane Claire McHenry. Jane is a big enthusiast of sea glass and proud owner of the online boutique Sea Glass Jewelry by Jane since 2009 which you can visit at https://seaglassjewelrybyjane.com/.

According to Jane, part of the reason why sea glass is so captivating is the length of time it takes to create. It can take decades, even as long as 100 years, to evolve a piece of everyday glassware into a beautiful, gem-like piece like those so popular and collectible today. In fact, you could call sea glass a “reverse gemstone. SG is also widely appreciated as mystical materials, in the same way as various minerals and their varieties. SG can be summarized as follows: From Trash to Treasure. For Jane McHenry, the symbolism resonates, for finding a special piece of sea glass can be a mystical experience, a commune with nature as we walk along the shore, picking up pretty rocks and driftwood, and discovering that lone piece of beautiful colored glass that we can carry in our pocket as a comforting reminder of nature’s wonders.

Sea glass takes 20–40 years, and sometimes as much as 100–200 years, to acquire its characteristic texture and shape. (LAMOTTE, 2015). However, the artifacts, of course, could be decades to thousands of years old.

Glass has been made by humans for thousands of years, 4,000 or more. The people of Mesopotamia were able to create glass in open molds by mixing quartz sand (silica), soda and lime, for example. But you will have to be very lucky to find a fragment of glass from an object as old as these. The oldest known piece is 1,500 years old, an Egyptian blue cup, you can very well find pieces that are 200 years old. Finding them whole is unlikely, but large shards or bottle bases often make their way to coastal regions from the seas (https://www.recyclethesea.co.uk/post/the-history-of-sea-glass#:~: text=Whilst%20you%20would%20be%20incredibly,often%20land%20on%20the%20shorelines.). Dating glass bottles is not so simple and information about this can be obtained at https://sha.org/bottle/glassmaking.html; Summary Guide to Dating Bottles (sha.org).

An expressive characteristic of SG is “frosted” surface – and this is also highly prized. This frosting is the result of a very slow creation process that involves time, salt water, sand and rocks, and the wear on any given piece is not necessarily even. Authenticity can be judged by extreme close-ups of the surface of a pieces of genuine sea glass, for example the crescent shaped C mark on the piece is an indicative on authentic SG. https://web.archive.org/web/20160623093451/http://www.northbeachtreasures.com/ natural-sea-glass.html).

Global location plays a role in how much glass washes up on the beach, along with coastal erosion, shipping lanes and whether there were ports in that location. For example, in the United Kingdom, glass is most prolific in Seaham, in the Northeast of England, where there was a glass factory that released excess product into the sea. For this reason, glass is not only prolific here, but also incredibly interesting in color. And so there are many other examples in places of glass trade and production throughout history: the Far East, China, Greece, Italy, Egypt, and even in the Caribbean.

Certainly, for many sea glass hunters, smooth pieces are the best finds, visually pleasing, they look like jewels made at sea, often perfectly circular or teardrop shaped. They can be turned into art, jewelry, and other household items, or kept in a collection on display. (https://www.recyclethesea.co.uk/post/the-history-of-sea-glass#:~:text=Whilst%20you%20would%20be%20incredibly,often%20land%20on%20the%20shorelines).

For more information, we recommend visiting the beautiful and rich websites focused on sea glass. It is worth it. It is very gratifying to enter this world of beauty and history, and why not, to oppose the radicalism that the human being is simply a great destroyer. From trash to jewelry. In the REFERENCES item, some of these sites are listed, which were consulted and cited in this work.

Sea Glass (SG) in the Azores Archipelago, Portugal

Although well known for its importance at the time of the great navigations and discovery of the New World, from the 15th century onwards, by the Portuguese and other explorers of the seas, and today for the attraction it exerts on tourists from all over the world, the Azores Archipelago, in particular the island of São Miguel dos Azores, the largest of the nine that make up the group, also has sea glass on its beautiful shorelines/beaches that surround geological young volcanic buildings, on which the archipelago was established. These are black sand to pebble beaches, which receive many exotic materials, especially sea glass. Horta (2024, in this issue) is a persistent and investigative observer of the shorelines of the Azores, and has collected many minerals and rock pebbles, and in this foray, has found many beautiful possible SGs. The three studied here come from her rich SG and mineral collection.

The second author, an Azorean gem, found on the shorelines of this archipelago a mine, or several mines, to mine minerals and associated minerals, the vast majority coming from rocks formed by young volcanism, and reworked by sea waves. She has found several examples of glass (Fig. 2), which, due to their general mesoscopic characteristics, can be classified as “genuine (natural) sea glass”. This work describes and characterizes three of such sea glass pebbles collected by her on the island of São Miguel dos Azores.

Figure 2 – On the left image single green sea glass pebble at the beach from São Miguel dos Azores; on the right a set of collected sea glass in the same place. Images captured by Susana Horta in 2024.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling

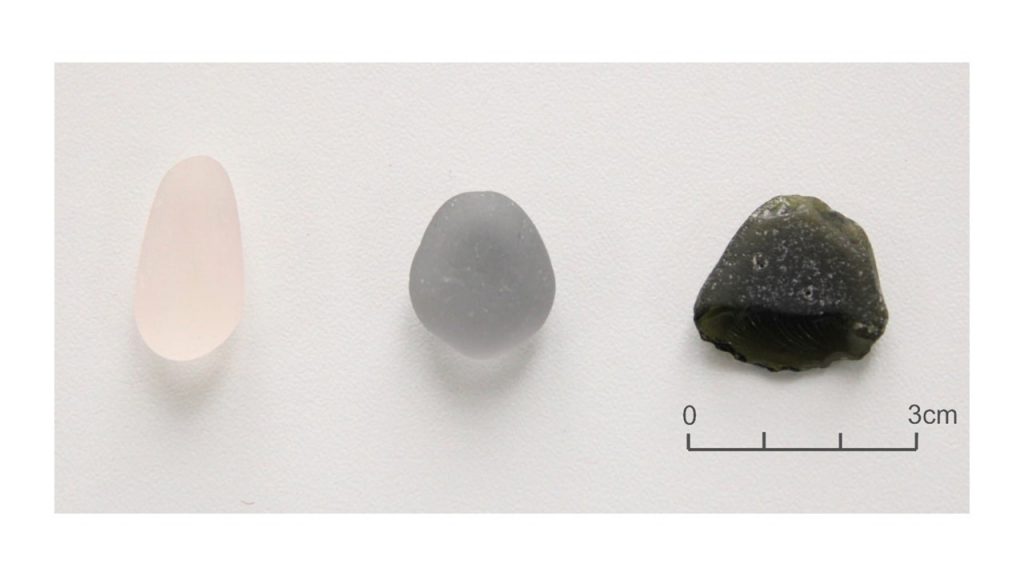

The three samples, called after dominant color white glass, blue glass, and black glass, were taken from the collection of sea glass collected on the beaches of São Miguel dos Azores by Susana Horta.

Analysis

Mesoscopical and physical properties – Encompassed the mesoscopic description of the samples (color, diaphaneity, brightness and superficial nature of the pebbles), determination of density, evaluation of Mohs hardness and ferromagnetism.

XRD mineralogy or crystalline phases – They were then subjected to mineralogical analysis by direct XRD on each “natural” sample. The Bruker D2 Phaser diffractometer, equipped with a Cu anode and Ni-k β filter, was used at the Federal University of Pará, Brazil. The diffractometer was set to θ-θ Bragg-Brentano geometry with a Lynxeye linear detector. The measurements run in the range of 5° to 70° 2θ with a step size of 0.02° and a counting time of 38.4s per step. The characterization of the mineral was carried out using the HighScore Plus 5.0 software, with the aid of the International Center for Diffraction Data (ICDD) Powder Diffraction Archives database.

Chemical analysis by handheld XRF (XRF handheld) – The three samples were subjected to non-destructive chemical analysis by X ray fluorescence (XRFhandheld). For this purpose, model S1-TURBO equipment manufactured by Bruker and belonging to MUGEO’s LAMIGA Laboratories was used, which does not detect chemical elements lighter than Mg.

Images capture and chemical analyzes by SEM-EDS – This was followed by the capture of images and semi-quantitative chemical analyzes by SEM-EDX, benchtop, Hitachi TM3000, coupled with an Energy Dispersive Fluorescence System (EDS) Swift ED300, under voltage acceleration from 5 to 15 kV and with an SDD detector (161 eV-Kα) from the Geosciences Institute of the Federal University of Pará. The analysis was carried out under low vacuum. The sample was not metallized.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

General features

The white and blue sea glass pebbles (Fig. 3) are oval or drop-shaped, with the white one being more elongated, measuring 3 cm and 2 cm respectively. They are well rounded and have a matte (frosted) surface. They are slightly translucent. The black sea glass, on the other hand, has a triangular shape, displays almost sharp edges, and flat but frosted surfaces, with strong abrasion cavities. It measures around 2.5 cm in length. The density of the white, blue and black sea glass is 2.36; 2.64; 2.56, respectively. Therefore, blue and black have densities closer to each other and to that of quartz (SiO2), the main source of raw material, while white is much lower. All are non-magnetic and the hardness is on the order of 6. These properties are compatible with the most common glasses (Tab.1), whose densities vary depending on the respective chemical composition.

Table 1 – Some glass densities for comparison to investigated Azores Sea glass.

| GLASS TYPES | DENSITY g/cm3 |

| Sand | 1.52 |

| Fused silica (96%) | 2.18 |

| Corning vycor® 7907 uv-blocking glass | 2.21 |

| Pyrex(r) | 2.23 |

| Borosilicate glass | 2.4 |

| Ordinary bottle | ~2.4-2.8 |

| Ordinary window | ~2.4-2.8 |

| Corning 0211 zinc borosilicate glass | 2.53 |

| Corning 1724 aluminosilicate crushed/powdered glass | 2.64 |

| Crown glass | 2.8 |

| Corning 0159 lead barium crushed/powdered glass | 3.37 |

| Lead crystal | 3.1 |

| Corning 8870 potash lead crushed glass | 4.28 |

| Densest flint optical | 7.2 |

Source: https://chem.libretexts.org/Ancillary_Materials/Exemplars_and_Case_Studies/Exemplars/Forensics/Glass_Density_Evidence

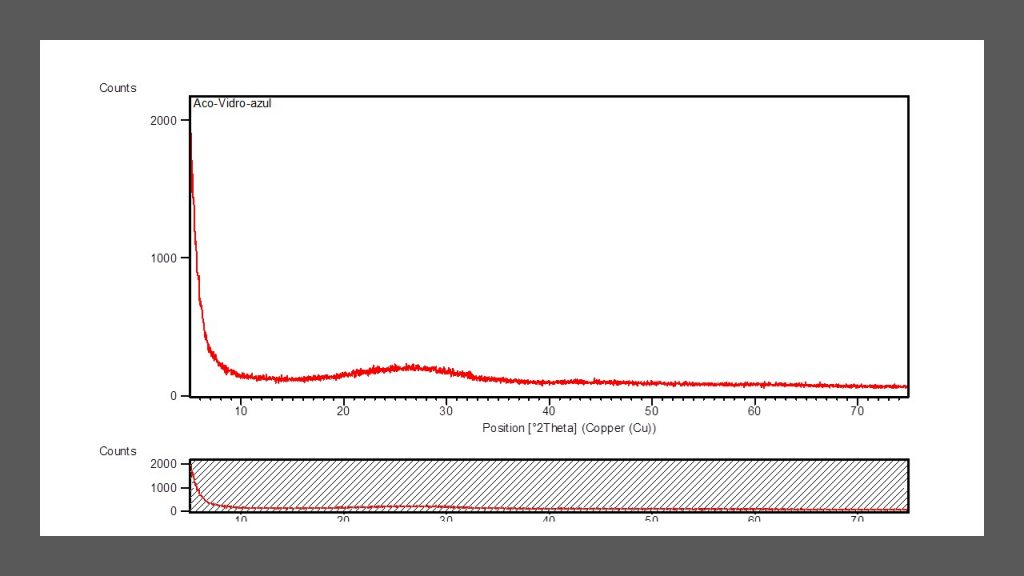

XRD mineralogy

The three sea glass samples are completely amorphous in XRD, all exhibiting the same diffractometric profile (Fig. 4, for the blue glass pebble), confirming the amorphous nature, a classic characteristic of man-made glasses.

Figure 4 – XRD spectrum for blue sea glass, which is like white and black ones. It displays a typical profile for amorphous material with very slight shoulder or low relief.

XRF handheld chemistry

Semiquantitative chemical composition by portable XRF (Tab. 2) shows that the three samples are equally dominated by SiO2. However, they differ in the content of the other components. Black and white are calcium, CaO and poor in potassium, K2O, while blue is potassium rich. Only black presents significant values (>0.2%) of iron (Fe2O3) and manganese (MnO). Aluminum (Al2O3) is present in blue and black in the same order of magnitude. Chlorine was detected in all three and S only in blue and black. The high value of titanium (TiO2) and even V in blue stands out. Glasses normally contain sodium, its absence in these analyzes is due to instrument limitations. The absence of Ba is due to the analytical method, which does not provide for this element in its analytical library. The presence of this element will be demonstrated by SEM-EDS analyses. MgO was observed only in black and white (in values, 1.2 and 0.3%, respectively; these are low precision values). Arsenic was detected in white sea glass and nickel in blue.

The chemical composition of the three SGs investigated, when compared with the data available for waste bottles glasses (Tab. 2, KEAWTHUN et al. 2014) shows that they are equivalent in terms of SiO2 content, but they differ greatly in the contents of iron, aluminum, calcium, potassium and phosphorus, which was not detected in the SG of this work. What can be concluded is that SG contain the same components as most waste bottle glasses, except phosphorus, but in different values with them and with each other. This large variation is observed in most glass artifacts, which depends on the diversity of raw materials and production processes throughout the production history of glass and geography. Except for SiO2, which corresponds to the fundamental raw material, the others correspond to additives such as fluxes, opacity, pigmentation or coloring, which vary according to different processes and producers and the season (Green and Hart, 1983; Lin et al., 2023; Li et al. 2023).

Table 2 – Chemical composition of the investigated sea glass pebbles from São Miguel dos Azores (XRF handheld) investigated in this paper compared to those from waste bottle glasses published by KEAWTHUN et al. 2014*. (-) not detected. Nd: not determined.

| Chemical compositions (Weight %) | Sea glass from Azores | Waste bottle glasses* | ||||

| White | Blue | Black | White | Green | Brown | |

| SiO2 | 82.20 | 77.90 | 78.50 | 75.54 | 71.80 | 79.46 |

| Al2O3 | – | 4.68 | 4.37 | 0.60 | 1.55 | 0.91 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 2.29 | 3.90 | 4.50 | 5.28 |

| CaO | 7.01 | 0.30 | 14.20 | 3.92 | 3.45 | 2.09 |

| MgO | 0.3 | – | 1.2 | 1.80 | 2.10 | 0.85 |

| Na2O | Na | Na | Na | 3.86 | 4.57 | 1.39 |

| K2O | 0.27 | 5.58 | 1.14 | 5.06 | 3.14 | 3.95 |

| P2O5 | – | – | – | 2.34 | 1.36 | 1.86 |

| TiO2 | – | 6.75 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.58 |

| MnO | – | 0.16 | 2.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| V | – | 0.63 | – | |||

| S | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.22 | |||

| Cl | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.13 | |||

| As | 0.37 | – | – | |||

| Ni | – | 0.14 | – | |||

| LOI | Nd | Nd | Nd | 1.54 | 2.67 | 0.82 |

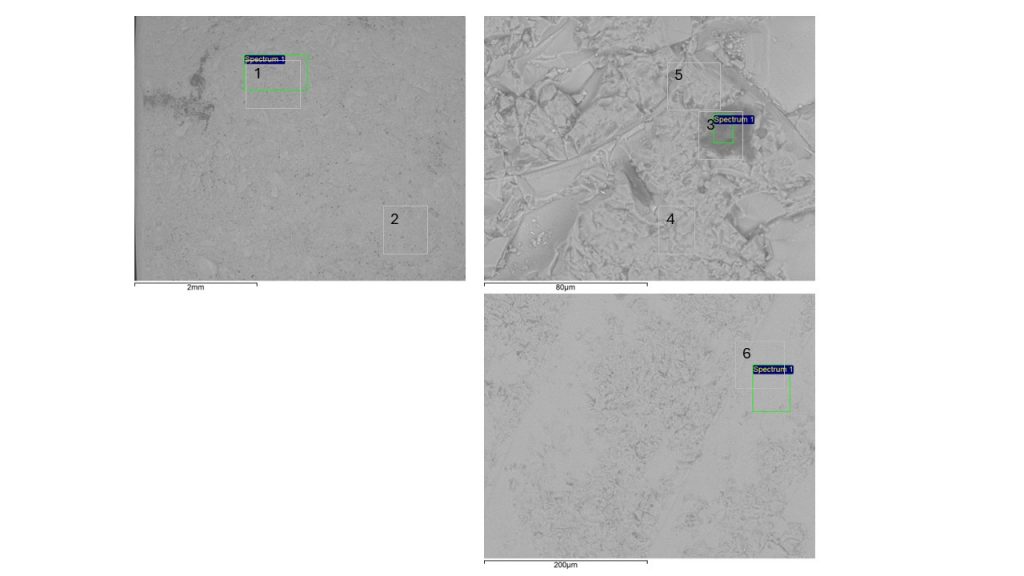

SEM-EDS micromorphology and chemistry

The results of the semiquantitative chemical analyzes obtained by SEM-EDS allowed the identification of a more complex and variable chemical composition than by XRF, although the analyzes are punctual and in micro area, and therefore show that although only three SGs, two (white and blue) are chemically similar and distinct from black one, but compatible with the composition of historic glass.

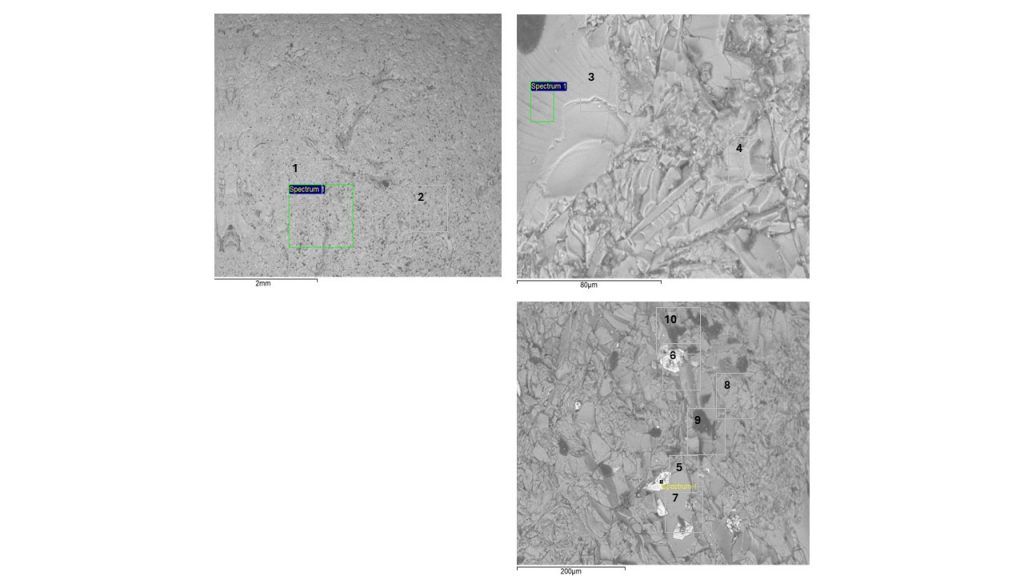

The white and blue sea glass pebbles

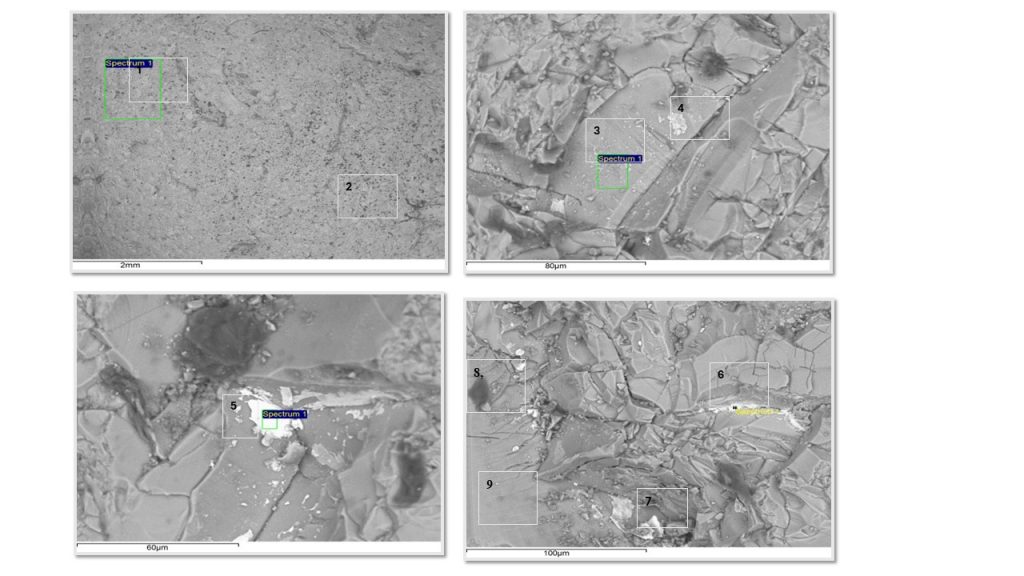

Regarding the main chemical composition, white and blue sea glass from São Miguel Azores display the same composition (Tab.3 and 4; Fig. 5 and 6). Semiquantitative chemical analyzes obtained at several different points in the white and blue glass show that they are mainly made up of O, Si, Ba, Na, K and Al (above 1%), while the levels of Ca, Cl and S are generally below 1.5%. Si contents are the highest, dominating values between 28 and 32%, which corresponds to 60 to 68% SiO2. These values are slightly lower than those pre-historic to historic glasses (-800 BC and A.D. 800 to 1700) rich in MgO (Henderson, 2013). The chemical composition of glasses varies depending on time and geography (Henderson, 2013), which recognizes glasses with high Mg, or high Pb, or high Sb, with natron/low Mg. The high Si values demonstrate the origin of the fundamental raw material, such as quartz or almost pure quartz sand, without Fe and Ti, but with Al, which is structural and normal in this mineral, or from the use of aluminosilicate, such as feldspar. These two elements were identified at low levels only by XRF. Fe and Ti were not identified by SEM-EDS at any analytical point in the white and blue glasses. The white and blue glasses investigated here stand out for their high sodium-potassium-barium components, partly distinct from those from Pompeii (De Francesco et al., 2019) and from Asia (Henderson, 2013), devoid of Ba. However, ancient Ba glasses are reported by Li et al (2023). Ba stands out in ancient Chinese lead-barium glass, which was very brittle due to the high presence of Pb, and not used for bottles (Kim, 2012).

While sodium and potassium present similar values, between 1 and 6%, barium is higher, 7 to 55%. The most frequent values are between 11 and 16% Ba. The highest values correspond to “amorphous” or dispersed microcrystalline phases dominated by Ba, either as oxide in white glass or even as sulfate (barite), inferred in blue glass, in which S contents are higher. Sulfur is detected in most of the points analyzed in the blue glass, with values from 0.3 to 6%, with a strong correlation to high Ba contents (Tab.4 points 6 and 7; Fig.6, points 6 and 7). It is likely that the raw material for Ba was barite, BaSO4, which when calcined forms BaO, and locally still retains barite residue. This was not identified by XRD, as it is restricted to micrometric manifestations, shown by SEM-EDS analyses. Ca contents in general are below 1%, those higher, with up to around 4%, are related to the highest Ba values. Al contents vary between 0.6 and 1.5% and show a positive correlation with Si, suggesting its relationship with aluminosilicates, whether clay or feldspar. But such low levels may simply reflect the structural levels of Al in the basic raw material quartz, normally as Al-center (Cohen, 1960; Weil, 1975; Götze et al., 2021). Chlorine was detected in almost all analyzes, and values varied between 0.3 and 0.8%, except in two points, when it reached 5.6% (Tab. 3, analysis 10, white glass) and 15.0% (Tab.4, analysis 8, blue glass). The first corresponds to one of the dark gray zones (inclusion or cavity) (Fig. 5, point 10), with no clear relationship with Na and K, while the highest value (Fig. 6, point 8) correlates with high value of Na, also in a dark gray zone depicting inclusion or cavity. It is interesting that Cl is always reported in the composition of historical glasses and is very striking in plant ash glasses. Cl, S and P is also reported in Roman and Wealden Glass (Green and Hart, 1987). However, the absence of P in the two glass fragments analyzed is surprising. It is always reported in the chemical composition of glasses, in values that reach percentage units (Li et al. 2023; De Francesco et a. 2019). In ash it is common alongside Cl.

Practically the only divergence between these two glasses was the sporadic detection of cobalt in blue. In glasses with blue tones promoted by Co, it is generally found in low levels (0.025 to 0.1%) (Qudratkho’dja’s Qizi and Azizov Olimjon Tahirovich, 2022), 0.3% CoO (Green & Hart, 1987). Therefore, the presence of cobalt in blue glass would confirm its possible importance for its blue color. The raw materials used are therefore the same: pure quartz silica (without Fe, Mn and Ti), soda and potash (ash) and calcined barite. Barium serves as an opacifier and stabilizer. Another important constituent was certainly soda (ash), potash (K hydroxide, generally obtained in ash), both, as flux. In part, they were still present as chlorides, considering that traces of chlorine are still found in the glass and point 8, a dark spot, shows a high concentration of Cl, possibly a relic of these salts. The origin of soda may be natron (https://edu.rsc.org/resources/roman-glass-and-its-chemistry/1962.article), already used by the Romans. Natural natron is a mixture of natron, NaHCO3, with Na chlorides and sulfates. Chlorine and S were detected, but carbon was not. Therefore, it is most likely that he used ashes. Calcium stabilizes the glass obtained, reducing its solubility, its low levels demonstrate that it was not necessary. Calcium from lime may also have been obtained from shells (https://edu.rsc.org/resources/roman-glass-and-its-chemistry/1962.article), certainly previously calcined. But no trace of carbon, which is generally present, was detected. In summary, the raw materials used were quartz silica (pure quartz sand), calcined barium sulfate (Ba, S), ash or natron (Na, K; and Ca, Mg) and cobalt.

Table 3 – SEM-EDS chemical composition of white sea glass pebble from São Miguel Azores, Portugal.

| Elements | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Oxygen | 44.157 | 41.386 | 52.513 | 41.479 | 30.884 | 28.817 | 45.920 | 39.946 | 41.918 | 39.757 |

| Sodium | 6.029 | 5.864 | 6.908 | 5.070 | 3.537 | 3.181 | 6.028 | 4.795 | 6.170 | 6.151 |

| Aluminum | 1.370 | 1.507 | 1.221 | 1.417 | 0.771 | 0.619 | 1.347 | 1.478 | 1.350 | 1.075 |

| Silicon | 30.720 | 30.945 | 28.488 | 32.256 | 8.326 | 6.559 | 30.538 | 34.034 | 29.120 | 24.093 |

| Sulfur | 0.345 | |||||||||

| Chlorine | 0.397 | 0.640 | 0.794 | 0.701 | 5.614 | |||||

| Potassium | 4.013 | 4.465 | 3.010 | 4.533 | 1.207 | 1.182 | 4.171 | 5.161 | 4.411 | 5.203 |

| Calcium | 0.555 | 3.634 | 3.987 | 0.833 | 1.353 | |||||

| Barium | 12.969 | 14.639 | 7.860 | 15.245 | 50.847 | 54.953 | 11.997 | 14.586 | 16.198 | 16.754 |

Figure 5 – SEM images from white glass pebble collected at São Miguel Azores beach and analyzed for this paper. The numbers indicate the sites of SEM-EDS chemical analyzes indicated in table 3. (1) e (2): glass matrix; (3) conchoidal glass surface; (4) Ba-rich “grain”; (5) and (6) Barium oxide relicts (white spots); (7) grained glass matrix; (8) grained glass matrix; (9) and (10) bubbles/inclusions on glass matrix (dark gray spots).

Table 4 – SEM-EDS (Hitachi) chemical composition of blue sea glass pebble from São Miguel Azores, Portugal.

| Element | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Oxygen | 46.615 | 45.421 | 42.517 | 44.725 | 43.341 | 35.950 | 42.804 | 38.981 | 40.036 |

| Sodium | 6.271 | 5.934 | 5.430 | 5.473 | 5.483 | 3.677 | 4.087 | 8.336 | 5.075 |

| Aluminum | 1.423 | 1.229 | 1.433 | 1.522 | 1.311 | 0.860 | 1.288 | 0.968 | 1.565 |

| Silicon | 29.928 | 29.863 | 28.905 | 29.725 | 22.832 | 16.157 | 15.045 | 21.631 | 32.939 |

| Sulfur | 0.344 | 0.879 | 0.771 | 6.329 | 5.930 | ||||

| Chlorine | 0.409 | 0.313 | 0.553 | 12.803 | |||||

| Potassium | 3.617 | 4.137 | 4.572 | 4.079 | 2.620 | 2.144 | 1.790 | 4.509 | 5.017 |

| Calcium | 0.373 | 0.547 | 0.559 | 1.120 | |||||

| Barium | 11.020 | 12.870 | 17.142 | 13.597 | 23.329 | 34.266 | 26.254 | 11.652 | 15.019 |

| Magnesium | 0.584 | 1.689 | 0.349 | ||||||

| Cobalt | 0.033 |

Figure 6 – SEM images from blue glass pebble collected at São Miguel Azores beach and analyzed for this paper. The numbers indicate the sites of SEM-EDS chemical analyzes presented in table 1. (1) and (2) glass matrix, basically: O, Si, Ba, Na and K; (3); a tabular domain of Ba oxide; (4) similar composition to (3) over slight whitish spot; (4) and (5): domains of barium oxide (white spots or crystals); (6) and (7) barite domains (whitish spots or crystals); (8) O, Si, Cl, Ba, Na and K; Co: dark gray spot (bubble/inclusion); (9) homogeneous glass.

Black sea glass pebble

The chemical composition of black sea glass is comparable to that of white and blue sea glass regarding the contents of Si, Na, Al and Mg, however it differs greatly in those of K (low), Ca (high), in the absence of Ba and characteristic presence of Fe, Mn and Ti (Tab.5). Therefore, while white and blue glasses are characterized as sodium-potassium-barium, black glass is sodium-calcium. Ca contents vary from 6.7 to 8.2%, while Mg practically does not vary and is always present (Tab.5). Chlorine and sulfur were restrictedly detected. The analytical point in the dark gray zone (Fig. 7, point 3), with the single values of S and Cl, is equivalent to those of white and blue glass, reflecting inclusion or cavities. Therefore, the additive raw materials were very different, except with regard to SiO2 (silica), in levels similar to previous glasses, probably quartz in the form of sand, which was the situation, but common at the time) as the basic raw material. , with the addition of soda (probably ash, hence the presence of K and sporadic presence of chlorine and sulfur), lime (CaO) and Fe oxides (hematite and/or goethite, or even Fe and Ti oxide (ilmenite), whose contents vary from 0.8 to 1.6; and Mn (for example pyrolusite, romanechite), among others), with contents of 1 to 1.5% of Mn (Tab.5). Mn oxides were probably mainly responsible for the black color of the glass, in fine particles, difficult to be visualized in SEM-EDS images (Figure 7). It can be concluded that black sea glass is very different from the other white and blue, in color, obviously, and in chemical composition, except for the Al and Si contents, in which Al must also be contained in the quartz structure of the raw material. Plant ash was probably not used.

Table 5 – SEM-EDS (Hitachi) chemical composition of black sea glass pebble from São Miguel Azores, Portugal.

| Elements/Point Analyses | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % | Weight % |

| Elements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Oxygen | 50.625 | 50.569 | 45.613 | 52.030 | 51.941 | 53.394 |

| Sodium | 6.126 | 5.808 | 6.986 | 6.544 | 6.457 | 6.643 |

| Magnesium | 0.462 | 0.450 | 0.530 | 0.507 | 0.478 | 0.532 |

| Aluminum | 1.733 | 1.672 | 2.506 | 1.661 | 1.497 | 1.580 |

| Silicon | 28.864 | 29.128 | 30.473 | 28.885 | 29.086 | 28.282 |

| Potassium | 0.889 | 1.016 | 1.782 | 0.750 | 0.716 | 0.628 |

| Chlorine | 1.478 | |||||

| Sulfur | 0.881 | |||||

| Calcium | 7.749 | 8.187 | 7.587 | 6.890 | 7.217 | 6.744 |

| Titanium | 0.471 | 0.516 | 0.385 | 0.339 | 0.368 | |

| Manganese | 1.470 | 1.361 | 0.996 | 1.233 | 1.136 | 1.008 |

| Iron | 1.612 | 1.292 | 1.169 | 1.114 | 1.134 | 0.820 |

| Total | 98.179 | 99.033 | 97.594 | 98.357 | 98.468 | 97.651 |

Figure 7 – SEM images from black glass pebble collected at São Miguel Azores beach and analyzed for this paper. The numbers indicate the sites of SEM-EDS chemical analyzes indicated in table 2. (1) and (2): glass matrix: O, Si, Ca, Na, Fe, Mn; (3) bubble/inclusion (dark gray spot); (4) and (5) fine “grained” matrix; (6) matrix.

Table 6 – Results of EMPA-EDS analysis performed on 15 Pompeii glass samples. Elements are expressed in wt %. (-) below the detection limit. After De Francesco et al., 2019.

| Sample | Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | SO3 | ClO | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | FeO |

| VP2 | 16.45 | 0.57 | 2.45 | 68.89 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 1.87 | 0.58 | 8.38 | – | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| VP3 | 15.13 | 0.57 | 2.36 | 71.59 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 1.56 | 0.58 | 6.63 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.24 |

| VP5 | 15.73 | 0.47 | 1.95 | 71.91 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 1.66 | 0.45 | 5.79 | 0.05 | 1.16 | 0.36 |

| VP6 | 14.85 | 0.57 | 2.40 | 71.41 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 1.68 | 0.55 | 7.30 | – | 0.66 | 0.22 |

| VP4 | 16.19 | 0.60 | 2.26 | 70.60 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 1.63 | 0.45 | 7.13 | – | 0.40 | 0.23 |

| VP9 | 16.18 | 0.73 | 2.64 | 71.33 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 1.35 | 0.54 | 6.29 | – | 0.27 | 0.21 |

| VP12 | 14.51 | 0.51 | 2.46 | 72.35 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 1.62 | 0.45 | 7.27 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| VP16 | 17.40 | 0.58 | 2.44 | 67.88 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 1.19 | 0.72 | 8.12 | – | 0.47 | 0.36 |

| VP11 | 15.26 | 0.55 | 2.27 | 69.32 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 1.34 | 0.80 | 8.64 | 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.90 |

| VP13 | 17.60 | 0.66 | 2.43 | 66.94 | – | 0.28 | 1.73 | 0.47 | 7.80 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| VP7 | 18.39 | 1.46 | 1.66 | 66.32 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 1.62 | 1.36 | 5.95 | 0.16 | 0.76 | 1.05 |

| VP8 | 16.83 | 1.53 | 2.34 | 65.83 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 7.10 | 0.29 | 1.19 | 1.23 |

| VP10 | 14.23 | 3.25 | 2.07 | 64.41 | 1.48 | 0.32 | 1.27 | 1.95 | 8.23 | 0.20 | 0.87 | 1.34 |

| VP14 | 15.00 | 2.27 | 2.34 | 65.21 | 1.09 | 0.47 | 1.39 | 2.17 | 7.61 | 0.18 | 1.26 | 1.40 |

| VP15 | 17.28 | 2.35 | 1.76 | 64.69 | 0.90 | 0.43 | 1.79 | 1.40 | 7.44 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 1.15 |

Table 7 – Chemical composition of unclassified cultural relicts after Li et al., 2023.

| Relict Number | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 |

| Surface Weathering | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| SiO2 | 78.45 | 37.75 | 31.95 | 35.47 | 64.29 | 93.17 | 90.83 | 51.12 |

| Na2O | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| K2O | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.36 | 0.79 | 0.37 | 1.35 | 0.98 | 0.23 |

| CaO | 6.08 | 7.63 | 7.19 | 2.89 | 1.64 | 0.64 | 1.12 | 0.89 |

| MgO | 1.86 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 1.05 | 2.34 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Al2O3 | 7.23 | 2.33 | 2.93 | 7.07 | 12.75 | 1.52 | 5.06 | 2.12 |

| Fe2O3 | 2.15 | 0.00 | 7.06 | 6.45 | 0.81 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| CuO | 2.11 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 1.73 | 1.17 | 9.01 |

| PbO | 0.00 | 34.3 | 39.58 | 24.28 | 12.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 21.24 |

| BaO | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.69 | 8.31 | 2.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.34 |

| P2O5 | 1.06 | 14.27 | 2.68 | 8.45 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 1.46 |

| SrO | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 |

| SnO2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SO2 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 2.26 |

Source: Li et al. 2023.

CONCLUSIONS

The data obtained for the three SG pebbles from Azores, Portugal, fit probably into genuine SG, in which the white and blue are in terms of chemical composition comparable to each other and differ from the black. The first, white and blue, are sodium-potassium-barium, while the black is sodium-calcium. The main raw material common to all was natural silica probably coming from quartz or quartz sands, reinforced by the constant Al2O3 content and low Ti content, clear sands. If compared with most historical glasses, they can only be partially compared and stand out for the absence of phosphorus and carbon. The presence of sodium, potassium, chlorine, sulfur and partly Ca and Mg, suggests the addition of possible plant ash, and the presence of Ba, as an opacifier, its initial raw material, would have been barite. Sodium may have come from natron and calcium from lime. The blue color was partly due to a small amount of Co and the black color was attributed to the contents of Fe and Mn, in the form of oxides and/or hydroxides.

Acknowledgments

To CNPQ (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) for the support through the Grant and research productivity scholarship to M.L. COSTA (Grant Nr. 304967/2022-0).

REFERENCES

DE FRANCESCO A.M., SCARPELLI R., CONTE M. AND TONIOLO L. 2019. Characterization of roman glass from casa bacco deposit at Pompeii by wavelength-dispersive electron probe microanalysis (EPMA). Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry Vol. 19, No 3, (2019), pp. 79-91 Open Access. Online & Print. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3541106.

COHEN A.J..1960. Substitutional and interstitial aluminum impurity in quartz, structure and color center interrelationships., 13(3-4), 321–325. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(60)90016-0

GÖTZE, J., PAN, Y. AND MÜLLER, A.2021. Mineralogy and mineral chemistry of quartz: A review. Mineralogical Magazine (2021), 85, 639–664. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.72.

GREEN, L. R. AND HART, F. A. 1983. Colour and Chemical Composition in Ancient Glass: An Examination of some Roman and Wealden Glass by means of Ultraviolet-Visible-Infra-red Spectrometry and Electron Microprobe Analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science 1987, 14, 271-282.

HENDERSON J., 2013. Glass Chemical Compositions. In: Ancient Glass: An Interdisciplinary Exploration. Cambridge University Press; 2013:83-126.

HORTA, S. 2024. Sea glass e beach glass – Seu uso em joias, artesanato e colecções a partir do Arquipélago Azores, Portugal. BOMGEAM, 11 (4). This issue, DOI: 10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v112024i4a5SUH.

KEAWTHUN, M., KRACHODNOK, S. and CHAISENA, A., 2014. Conversion of waste glasses into sodium silicate solutions. Int. J. Chem. Sci.: 12(1), 2014, 83-91.

KIM, C.F., 2012. Early Chinese Lead-Barium Glass Its Production and Use from the Warring States to Han Periods (475 BCE-220 CE). ARCH0305 Prof. Carolyn Swan May 7, 2012.

LAMOTTE, R. 2015. The Godfather of Sea Glass. Sea Glass Journal. Retrieved February 19, 2015. https://www.seaglassjournal.com/articles/pureseaglass/lamotte.htm, accessed on august 9, 2024.

LIN, H., LIN, J., LIN, JIANZE. 2023. Analysis of the chemical composition of ancient glass products and identification of the types to which they belong. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, Volume 33 (2023).

LI, Z-X, LU, P.S., WANG, G-Y, LI, J-H, YANG, Z-H, MA, Y-P, WANG, H-H. 2023. Analysis of the Composition of Ancient Glass and Its Identification Based on the Daen-LR, ARIMA-LSTM and MLR Combined Process. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13(11), 6639; https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116639

QUDRATKHO’DJA’S QIZI, N.D. & TAHIROVICH, A.O. 2022. Glass Containers, Classification of Their Composition, Characteristics. Texas Journal of Engineering and Technology ISSN NO: 2770-4491 https://zienjournals.com, volume 14: 34-35.

WEIL, J. A. 1975. The aluminum centers in α-quartz. Radiation Effects, 26(4), 261–265. doi:10.1080/00337577508232999.

LIST OF MENTIONED AND CONSULTED SITES AND LINKS

https://sha.org/bottle/glassmaking.htm

Summary Guide to Dating Bottles (sha.org)

https://sha.org/bottle/bases.htm

https://sha.org/bottle/index.htm

https://edu.rsc.org/resources/roman-glass-and-its-chemistry/1962.article (natron)

https://ancientglass.wordpress.com/2014/05/19/what-is-the-chemistry-of-roman-glass/

https://ancientglass.wordpress.com/?s=sea+glass

https://www.scienceabc.com/nature/what-is-sea-glass-and-where-does-it-come-from.html

https://seaglassjewelrybyjane.com/where-does-sea-glass-come-from/

Sea Glass Articles, Stories (seaglassjournal.com)

https://www.seaglassjournal.com/articles/pureseaglass/lamotte.htm

https://www.seaglassjournal.com/articles/glassmuseum/sandwichglassmuseum.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20160623093451/http://www.northbeachtreasures.com/natural-sea-glass.html

https://sha.org/bottle/glassmaking.htm

Summary Guide to Dating Bottles (sha.org)

https://glassbottlemarks.com/pyrex-glass-corning-glass-works/