03 – HYDROTHERMAL SYNTHESIS OF SODALITE FROM BAUXITE WASHING CLAY AND ITS TRANSFORMATION INTO BETA-HEXACELSIAN-TYPE MATERIAL

Ano 12 (2025) – Número 3 – Mineral Synthesis Artigos

10.31419/ISSN.2594-942X.v122025i3a3BAMF

Bruno Apolo Miranda Figueira1*, Kauany Figueira Bastos2, Nayara Aparecida Fonseca Couto1, Renata de Sousa Nascimento3, Igor A. R. Barreto3

1Instituto Federal do Pará, IFPA-Campus Belém, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia de Materiais – PPGEMAT, figueiraufpa@gmail.com

2Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, UFOPA-Campus Santarém, Instituto de Engenharia e Geociências-IEG, Santarém, Pará, Brasil.

3Universidade Federal do Pará, UFPA-Campus Belém, Instituto de Geociências – IG, Belém, Pará, Brasil.

*To whom it should be sent a correspondences

ABSTRACT

In this work, b-hexacelsian (BaAl2Si2O8) type material was successfully obtained from the bauxite washing clay (BWC) from Amazon Region (Brazil), which was converted into zeolitic material type Na-sodalite. The route involved cation exchange of zeolite with Ba2+ ions, its subsequent thermal decomposition to form an amorphous barium aluminosilicate material from which b-hexacelsian recrystallized at higher temperatures (above 900º C).

INTRODUCTION

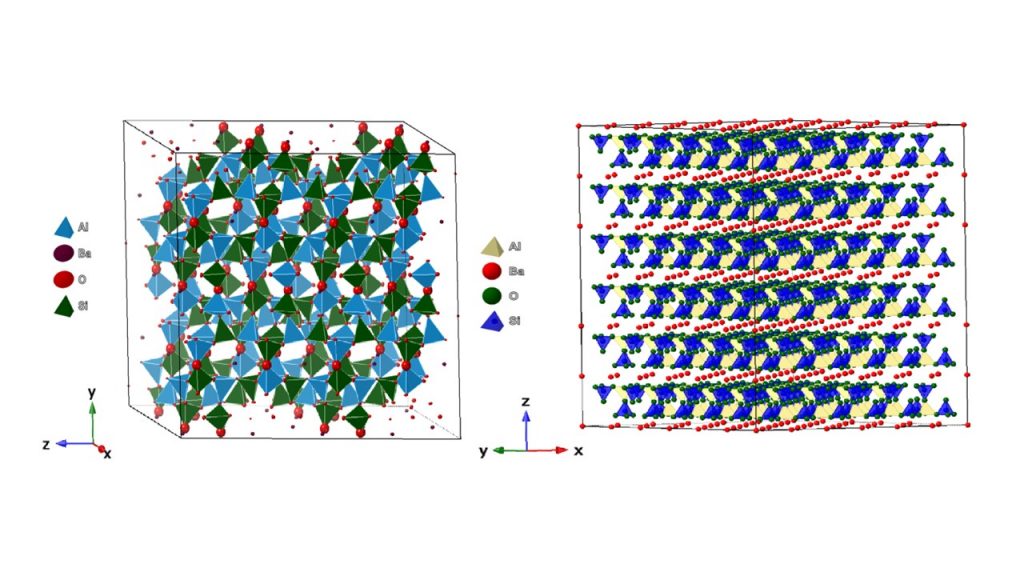

Celsian, ideally BaAl2Si2O8, is a rare barium aluminosilicate that occurs in metamorphic environments and was first reported by Igelström (1867) from manganese mines of Jakobsberg (Sweden) as “red feldspar, occurring in veins a few lines wide in a dense, light-colored, which itself is barite-containing” (Sjogren, 1895). It stands out in the felspar group due to its polymorphic diversity (Fig. 1), which is basically made up of TO4 tetrahedron units (T = Al, Si) connected by corners in a [Al2Si2O8] framework, large size of Ba2+ as out net cations and monoclinic symmetry with I2/m space group (Hoghooghi et. al., 1994; Skellern et al., 2002; Marocco et al., 2011; Radosavljevic-Mihajlovic et al., 2012; Radosavljevic-Mihajlovic et al., 2017). Another naturally occurring polymorph reported is monoclinic paracelsian with P21/a space group (Chiari et al., 1985). There are also two other polymorphic structures of BaAl2Si2O8, consisting of double layers of [Al2Si2O8] and Ba2+ ions interlayers with orthorhombic and hexagonal symmetries, known as a and b-hexacelsian, respectively (Dondur et al., 2005; Lopes-Badillon et al., 2013). It is important to emphasize that other cations can replace Al3+ and Si4+ (i.e., Ge4+ and Ga3+) in the TO4 units of the framework, as well as out net cations (i.e., Li+, Na+, K+, Co2+, Pb2+, Ca2+ and Sr2+), which makes it possible to obtain new structures of technological interest (Wang et al., 2016; Gorelova et al., 2024).

Figure 1- Illustration of the structure celsian (left) and b-hexacelsian (right) obtained by Vesta® software.

Due to its unique properties of corrosion resistance, very high thermal stability, mechanical strength, electrical and dielectric properties, this mineral phase has been widely investigated in terms of obtaining its synthetic analogue in the laboratory, modifications to its chemical composition, characterizations, and noble applications such as advanced ceramic, electrical insulation, materials for aeronautical applications and aerospace (Radosavljevic-Mihajlovic et al., 2015; López-Badillo et al., 2015).

There are several synthetic routes to produce celsian based on commercial reagents, including sol-gel, solid-state and hydrothermal reactions. Since the mid-1990s, there has been an extension to raw materials of natural origin (clay minerals), which after zeolitization process converts into celsian at high temperatures (> 1000 ºC). Among the most notable works are synthesis of celsian from faujasite and zeolite A-type zeolites, after heating at 1200º C. In addition, Sr-celsian has also been obtained from the zeolite described above, based on the feldspar slawsonite, which has the formula, (Sr,Ca)Al2Si2O8 SrAl2Si2O8, a monoclinic mineral (Ptáček et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2016).

This paper presents a study on the production of b-hexacelsian from Ba-rich sodalite material. It is worth noting that the zeolitic material was obtained from bauxite tailings from Amazon by Bayer-type conditions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The following reagents were used to produce the materials obtained in this work: NaOH (Neon reagent grade), BaCl2 (Neon reagent grade) and bauxite washing clay (BWC) collected at the Miltônia mine in Paragominas county, Pará state, belonging to the Hydro® mining company. For the synthesis of the sodalite phase, the methodology of Melo et al. (2017) was used, who synthesized sodalite from Bayer process conditions. Initially, an acid leaching experiment of BWC with 0.5 mol.L-1 of H2SO4 was used to remove hematite and gibbsite phases. After filtering and washing, the solid material (BWC-LIX) obtained was pulverized, mixed with NaOH and heated at 350º C/4h to obtain a fused material, which was then hydrothermally treated with 30 mL of deionized water at 90ºC/4h. The product was washed with deionized water, dried and coded as Na-ZEO. For the synthesis of Ba-sodalite, a simple cation exchange process was used by adding 1 g of Na-ZEO in a 1 mol.L-1 of BaCl2 solution at room temperature for 24 hours. The solid obtained was filtered, washed with deionized water, dried and coded as Ba-ZEO. Finally, b-hexacelsian was synthesized by heat-treating of Ba-sodalite (Ba-ZEO sample) at different range temperature (100 to 900º C), with a heating rate of 50° C min-1.

The chemical composition of BWC was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence (Axios Minerals, from Panalytical) spectrometer. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was measured in a D2 Phaser diffractometer (Bruker), copper tube (CuKa = 1.5406 Å) at 30 kV and 10 mA. FT-IR analysis was performed by using a spectrometer Vertex 70 (Bruker). SEM analysis (TESCAN Vega) was employed to obtain the morphology of the starting materials and synthetic products.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

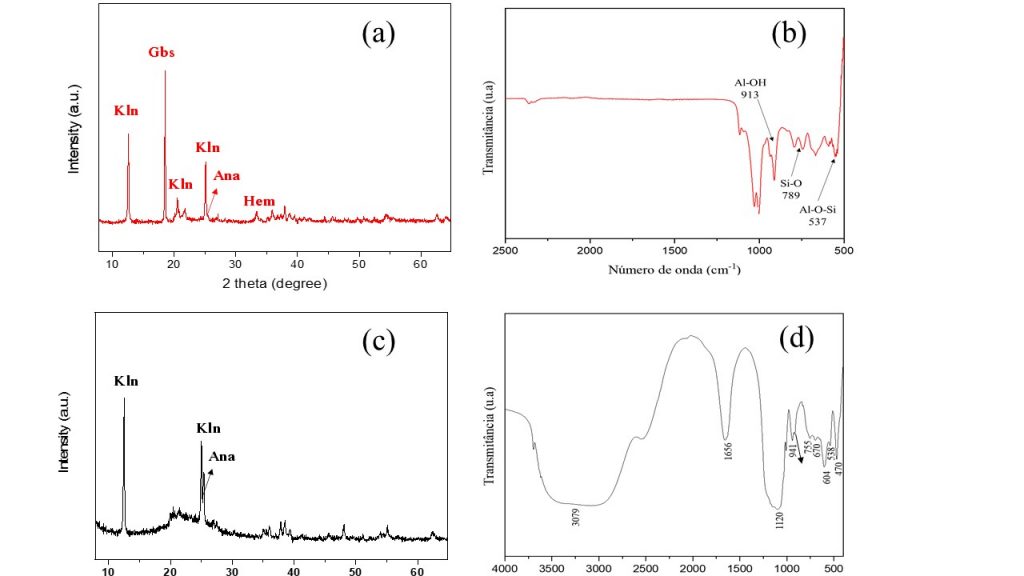

The chemical and mineral composition of BWC (Tab. 1 and Fig. 2a) showed that the starting material consisted of high levels of Al2O3 (43.6% m/m), SiO2 (29.2% m/m), Fe2O3 (22.3% m/m) and TiO2 (3.17% m/m). And is composed of gibbsite (PDF 00-012-0460), hematite (PDF 00-013-0534), anatase (PDF 01-078-2486), quartz (PDF 01-082-0512) and kaolinite (PDF 00-006-0221) were identified. A complementary FTIR spectroscopic characterization of the starting material was also carried out (Fig. 2b) and showed characteristic bands of Si-O stretching at 1101 and 789 cm-1 well correlated to the quartz mineral. The bands at 1033 and 913 cm-1 corresponded to the Si-O and Al-OH stretching in kaolinite structure, while the band at 537 cm-1 could be ascribed to the Fe-O vibrations of hematite (Fe2O3). Fig. 2c shows the XRD pattern of BWC-LIX, which indicates the absence of the hematite and gibbsite phases. Only kaolinite and anatase were identified in the sample, as also observed by the presence of FTIR bands of Al-O-H stretching at 3660 cm-1, Al-O-H at 914 cm-1, Si-O-Si at 670 cm-1 (Fig. 2d). The bands at 604 and 470 cm-1 were well correlated with the Ti-O vibrations of anatase (Iriarte et al., 2005; Saikia and Parthasarathy, 2010; Chougala et. al., 2017; Ahmad et al., 2021).

Figure 2 – XRD pattern (a) and FTIR spectra (b) of BWC. XRD pattern (c) and FTIR spectra (d) of BWC-LIX. (Kln = kaolinite, Gbs = gibbsite, Ana = anatase, Hem = hematite).

Table 1- Chemical composition of BWC.Table Tab. 1_Celsiana

Chemical elements as oxides |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

Fe2O3 |

TiO2 |

SO3 |

K2O |

ZrO2 |

Contents (Wt. %) |

29.2 |

43.6 |

22.3 |

3.17 |

0.227 |

0.134 |

0.251 |

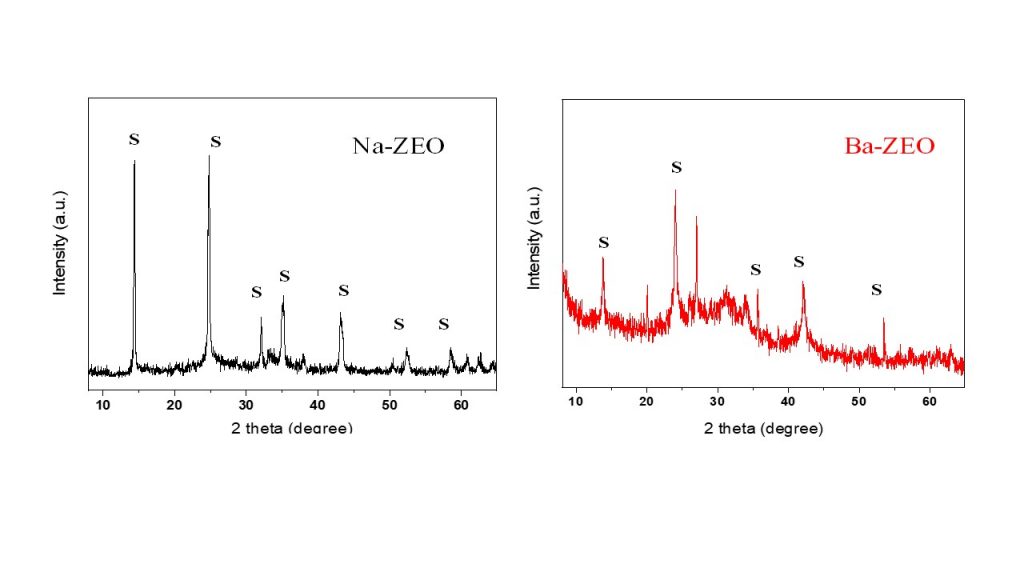

The XRD patterns of Na-ZEO and Ba-ZEO are shown in Fig. 3. For the Na-ZEO sample, the XRD pattern was characterized by well-defined peaks at 13.81°, 24.04°, 34.27°, 42.31°, 51.41° (2 theta), which corresponded to the (110), (211), (222), (330) and (431) planes of cubic sodalite (PDF 01-082-1812). The average crystallite size calculated using the Scherrer equation was 58 Å. On the other hand, the XRD pattern of Ba-zeo indicated disordering in the sodalite framework after ion exchange treatment with Ba2+ ions, as observed by the low intensity and definition of the peaks. In addition, amorphous material may be present in the Ba-ZEO sample.

Figure 3 – XRD pattern of Na-ZEO and Ba-ZEO. SO: sodalite.

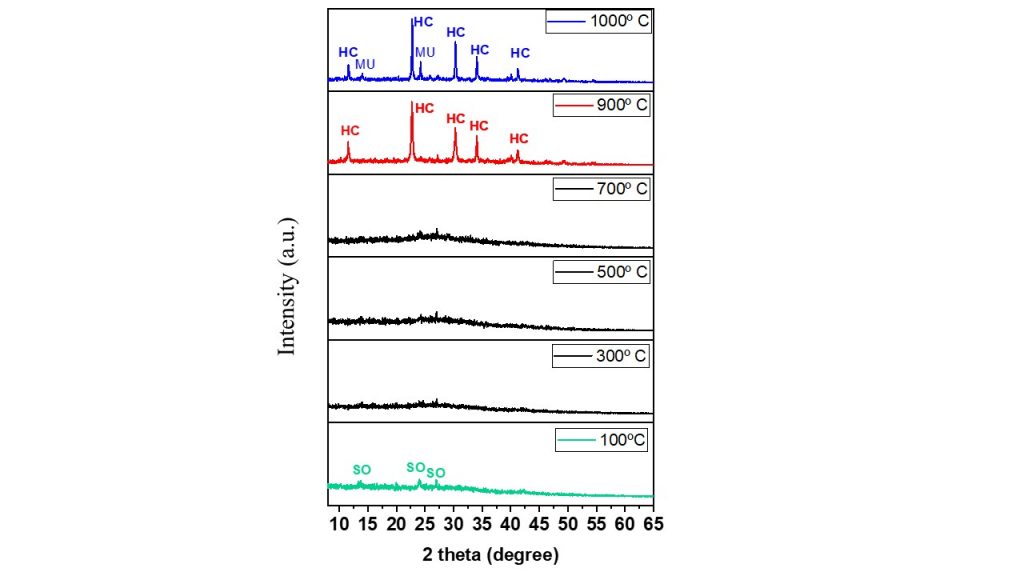

The thermal transformations of Ba-sodalite into celsian were monitored by XRD analysis and shown in Fig. 4. The results revealed that even at a relatively low temperature (100º C), the barium-doped sodalite structure showed a broadening of its main peaks with low intensity, suggesting an intense decrease in the ordering of the zeolitic structure. As the temperature increased, this disorder became more pronounced, and the structure probably transformed into a quasi-amorphous phase between 300-700º C. Up to 900º C, the XRD pattern revealed the presence of peaks at 11.48, 22.66, 30.26, 33.96 and 41.16º (2 theta), which were well correlated with the (001), (101), (012), (110) and (11-2) reflections of the hexacelsian phase (PDF 01-088- 1050). For the sample heat-treated at 1000º C, in addition to the hexagonal celsian phase, mullite (01-088-1050) was also identified. It is worth noting that these results for the thermal behaviour of Ba-sodalite are like those described for zeolite A and 13 X doped with Ba, which were synthesized to obtain celsian (Radosavljevic´-Mihajlovic et al., 2015; López-Badillo et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016).

Figure 4 – XRD pattern of BaZEO heated at 100, 300, 500, 700, 900 and 1000º C for 1 h. (SO = Sodalite, HC = hexacelsian, MU = Mullite).

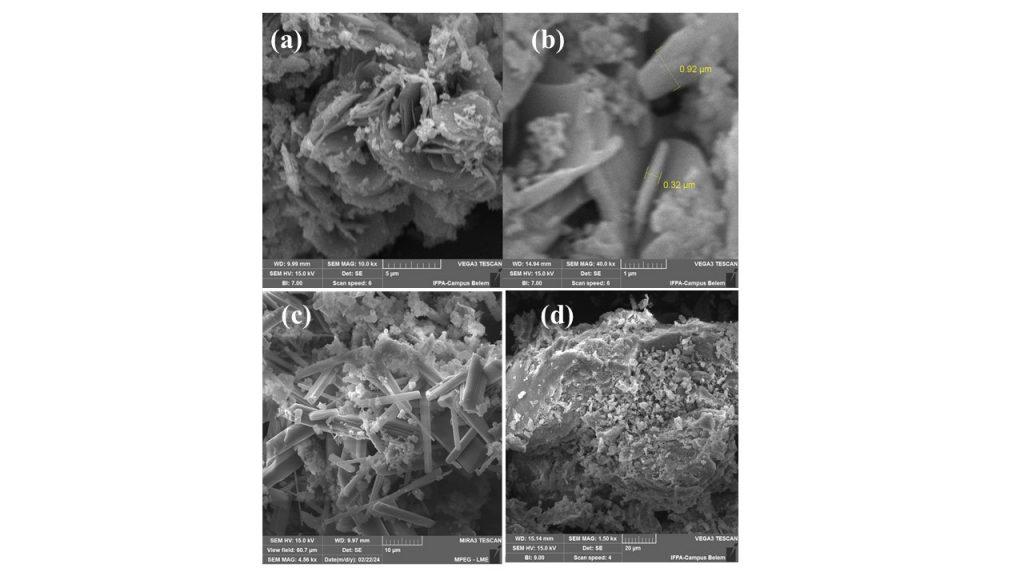

A morphological characterization of the starting material leached by H2SO4 (BWC-LIX), zeolitic precursor (Na-ZEO) and its product heated at 900 ºC (Ba-ZEO-900) were carried out by using scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 5). A pseudo-hexagonal plate morphology could be identified with an average size of 1 mm and thickness of 0.32 mm (Fig. 5a, b). This morphology is common in clay minerals and showed that kaolinite has preserved its plate morphology, despite of acid treatment over 12 h. For sodium sodalite sample (Fig. 5c), aggregates of sticks-shaped morphology with an average size of 15 mm and 1 mm thickness were observed. It is worth noting that this morphology differs from that in wool ball reported for sodalite obtained from kaolin tailings (Paz et al., 2010; Sousa et al., 2020), suggesting that pre-treatment by alkaline fusion may interfere the morphology of the final product. After the sintering process at 900 ºC, it was possible to observe a complete transformation of the sticks into aggregates with an undefined shape of hexagonal celsian (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5 – SEM analysis of BWC-LIX (a), Na-ZEO (b, c) and Ba-ZEO heated at 900º C (d).

CONCLUSIONS

The conversion of bauxite washing clay (BWC) from Amazon Region (Brazil) into b-hexacelsian-type material was proposed. Initially, the BWC was transformed into Na-sodalite, which presented sticks-shaped morphology. After ion exchange with Ba2+ ions, the sodalite structure underwent intense structural disorder, collapsed into amorphous barium aluminosilicate material, and recrystallized as pure b-hexacelsian up to 900º C. Our results have shown that a new and abundant raw material can be used to synthesize a product of great value to the ceramics industry.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, M.M., Mushtaq, S., Qahtani, A., Sedky, A., Alam, M.W. 2021. Investigation of TiO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Sol-Gel Method for Effectual Photodegradation, Oxidation and Reduction Reaction. Crystals, 11(12): 1456. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11121456.

Chougala, L.S., Yatnatti, M.S., Linganagoudar, R.K., Kamble, R.R., Kadadevarmath, J.S. 2017. A Simple Approach on Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles and its Application in dye Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Nano- Electron. Phys, 9:1-6. DOI: 10.21272/jnep.9(4).04005.

Chiari, G., Gazzoni, G., Craig, J. R., Gibbs, G. V., Louisnathan, S. J. 1985. Two independent refinements of the structure of paracelsian, BaAl2Si2O8. American Mineralogist, 70 (9-10): 969–974.

Dondur, V., Dimitrijević, R., Kremenović, A., Damjanović, L., Kićanović, M., Cheong, H. M., Macura, S. 2005. Phase Transformation of Hexacelsians Doped with Li, Na and Ca. Materials Science Forum, 494 (1): 107-112. DOI: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.494.107.

Gorelova, L., Britvin, S., Krzhizhanovskaya, M., Vereshchagin, O., Kasatkin, A., Krivovichev, S. 2024. Crystal structure stability and phase transition of celsian, BaAl2Si2O8, up to 1100 °C / 22 GPa. Ceramics International, In Press, Corrected Proof. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.10.336.

Hoghooghi, B., McKittri, J., Butler, C., Desch, P. 1994. Synthesis of celsian ceramics from zeolite precursors. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 170(3): 303-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3093(94)90061-2.

Iriarte, I., Petit, S., Huertas, F. J., Fiore, S., Grauby, O., Decarreau, A., Linares, J. 2005. Synthesis of kaolinite with a high level of Fe3+ for Al substitution. Clays and Clay Minerals, 53(1): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.2005.0530101.

López-Badillo, C.M., López-Cuevas, J., Pech-Canul, M.I. 2013. Synthesis and characterization of BaAl2Si2O8 using mechanically activated precursor mixtures containing coal fly ash. Journ. European Ceramic Society, 33(15-16): 3287–3300. DOI: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2013.05.014.

Marocco, A., Liguori, B., Pansini. M. 2011. Sintering behaviour of celsian based ceramics obtained from the termal conversion of (Ba, Sr)-exchanged zeolite A. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 31(11): 1965–1973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2011.04.028.

Melo, C. C. A., Paz, S. P. A., Angelica, R. S. 2017. Sodalite phases formed from kaolinite under bayer-type conditions. Revista Matéria, 22(3): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-707620170003.0196.

Radosavljevic-Mihajlovic, A., Prekajski, M.D., Nenadovic, S.S., Matovic, B.Z. 2012. Preparation, structural and microstructural properties of Ba0.64Ca0.32Al2Si2O8 ceramics phase. Ceramics International, 38(3): 2347–2354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.10.087.

Radosavljevic´-Mihajlovic, A.S., Prekajski, M.D., Nenadovic, S.S., Matovic. B.Z. 2015. Thermally induced phase transformation of Pb-exchanged LTA and FAU-framework zeolite to feldspar phases. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 201 (1) 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.08.059.

Radosavljevic-Mihajlovic, A., Radosavljevic, S., Stojanovic, J. 2017. The Crystal Structure of the Ba-Hexacelsian Phases Doped with Ca2+ and Pb2+. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Sci, 41(1): 599–607 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40995-017-0307-9.

Saikia, B.J., Parthasarathy, G. 2010. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Characterization of Kaolinite from Assam and Meghalaya, Northeastern India. J. Mod. Phys, 1(4): 206-210. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2010.14031.

Skellern, M. G., Howie, R. A., Lachowski, E. E., Skakle, J. M. S. 2003. Barium-deficient celsian, Ba1-xAl2-2xSi2+2xO8. Acta Cryst, C59: i11-i14. DOI: 10.1107/S0108270102023053.

Sjögren, H. 1895. Celsian, en anorthiten motsvarande bariumfältspat från Jakobsberg. Preliminärt meddelande. Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar, 17(6): 578-582. https://doi.org/10.1080/11035899509453948.

Paz, S. P. A., Angelica, R. S., Neves, R. F. 2010. Síntese hidrotermal de sodalita básica a partir de um rejeito de caulim termicamente ativado. Química Nova, 33(3): 579-593. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-40422010000300017.

Ptáček, P., Šoukal, F., Opravil, T., Bartoníčková, E., Wasserbauer, J. 2016. The formation of feldspar strontian (SrAl2Si2O8) via ceramic route: Reaction mechanism, kinetics and thermodynamics of the process. Ceramics International, 42 (7): 8170–8178.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.02.024

Sousa, B. B., Rego, J. A. R., Brasil, D. S. B.M, Martelli, C. 2020. Síntese e caracterização de zeólita tipo sodalita obtida a partir de resíduo de caulim. Ceramica, 66 (2020) 404-412. https://doi.org/10.1590/0366-69132020663802758.

Wang, D., Han, M., Li, M., Yin, X. 2016. Effect of strontium doping on dielectric and infrared emission properties of barium aluminosilicate ceramics. Materials Letters, 183: 223–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2016.07.113.